Worldviews at War

Worldviews at War

When Border Debates Feel Like Holy War: What Your Worldview Has to Do with ICE Protests

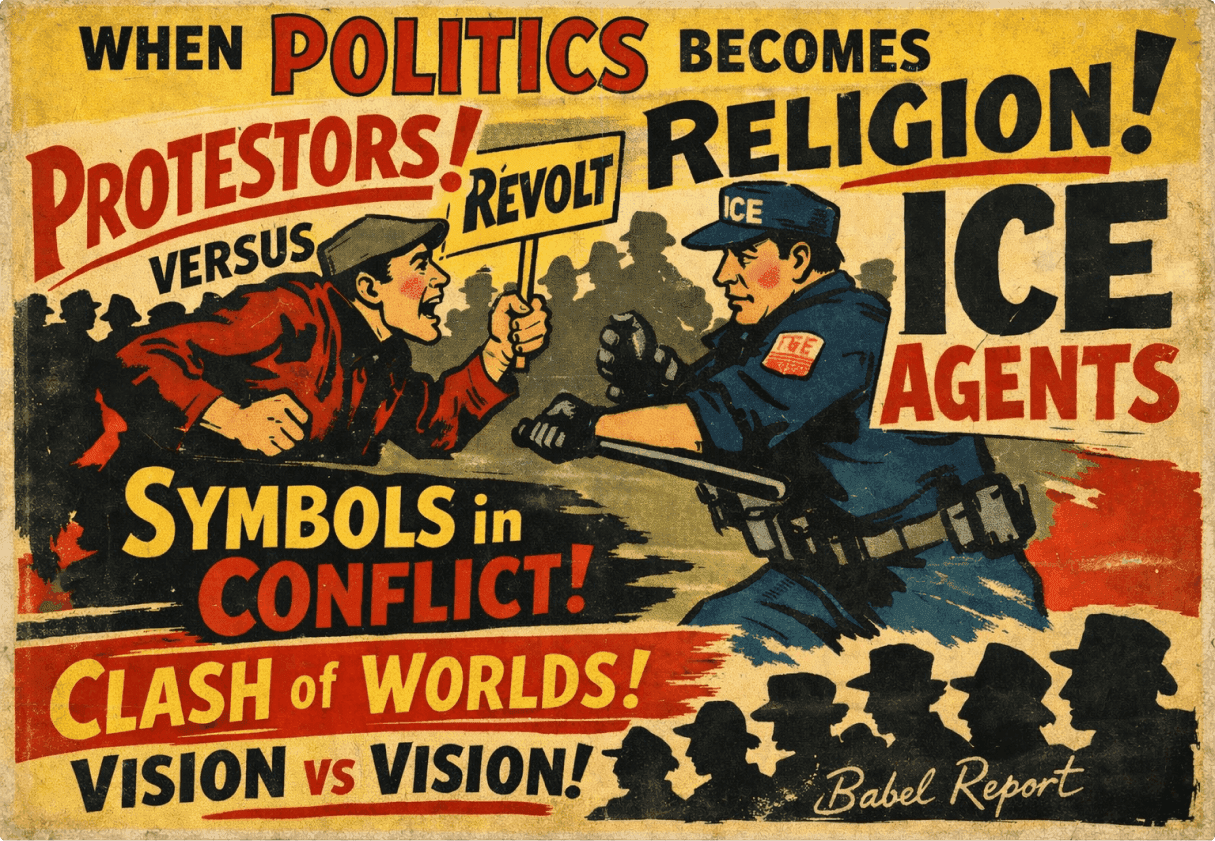

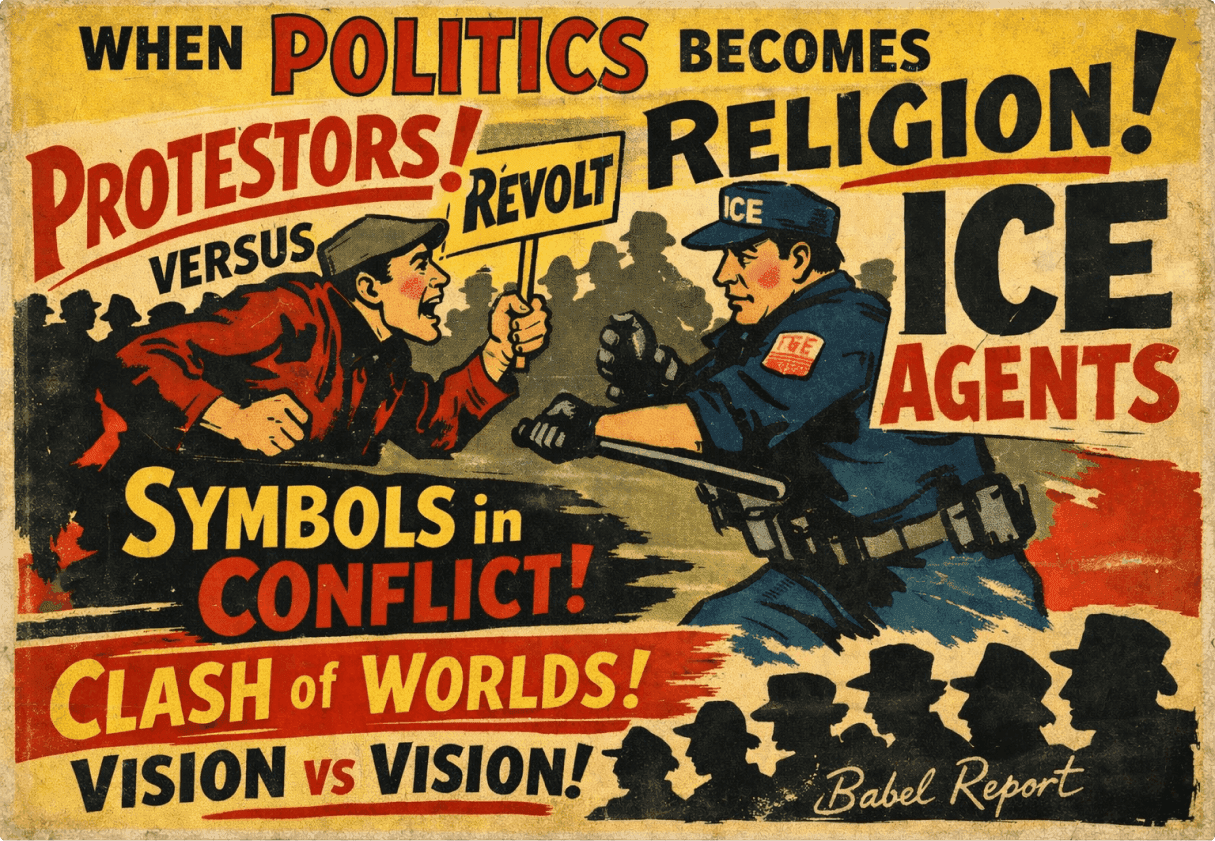

When we find ourselves bewildered by the sheer intensity of contemporary political debates (whether it's protestors confronting Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents or the impassioned defense of such institutions from the other side) we are witnessing something far more significant than a policy disagreement. We are witnessing people who have touched upon one of the most vital mysteries of human existence: the fact that we are rarely the neutral observers we imagine ourselves to be. You see, a worldview is not something you normally look at, but rather the very thing you look through. Think of it like a pair of spectacles. We do not often notice the lenses themselves unless they become dirty or out of focus. Even the person we might call the protester, who perhaps acts out of a sudden, fiery conviction without ever sitting down to map out their metaphysics, is still standing on a deep and usually invisible foundation.

This is because worldviews are the basic stuff of human existence, the presuppositional and pre-cognitive stage of our culture and society. We all possess a kind of social autopilot or practical consciousness that directs our steps long before we stop to think about where they are leading us. Every philosophy, every political system, and indeed every single child, woman, and man has a view of the world, though most people simply take these for granted until something goes wrong.

Now, you see, the reason the situation with ICE protests feels as though it has the weight and heat of a religion is that, for many in our modern Western world, it effectively is one. We have been taught for two centuries, since the Enlightenment, that religion is a private hobby and politics is the public reality of how we run the world, but this is a shallow and misleading dualism. In the first century, as today, when you touch a political issue, you are reaching down into the deep, hidden foundations of the house people live in. You are touching their worldview.

When you see people on the American left protesting ICE agents, and those on the other side defending them with equal ferocity, you are witnessing a clash of symbolic universes and clashing stories. Let us break this down using the elements of a worldview to understand why regular people are getting so worked up.

The Skeleton of Every Worldview

Before we can understand the heat of these debates, we must first understand what a worldview actually is and how it functions. A worldview is the basic framework through which human beings organize all their experiences and knowledge. It provides the implicit answers to a handful of foundational questions that every human being, every culture, and every civilization must answer in one way or another.

These questions are not the sort one typically asks at dinner parties, but they are the questions that determine how we will respond when the dinner party is interrupted by a knock at the door. They are: Who are we? Where are we? What has gone wrong? What is the solution? And what time is it? These five questions form the skeleton upon which all our beliefs, values, and actions hang like flesh on bones.

Consider the question "Who are we?" A person might answer: We are autonomous individuals pursuing happiness. Or: We are members of a covenant community bound by sacred law. Or: We are evolved mammals competing for resources. Each answer leads to radically different conclusions about how we should live and what we should value.

The question "Where are we?" asks about the nature of the world itself. Is this a cosmos created by a good God, a neutral machine governed by impersonal laws, or a kind of illusion from which we need to escape? Your answer determines whether you see the material world as something to be enjoyed, exploited, or transcended.

"What has gone wrong?" is perhaps the most revealing question of all. Every worldview acknowledges that something is not as it should be. The secular progressive says the problem is oppressive structures and unjust systems. The traditional conservative says the problem is moral decay and the abandonment of time-tested wisdom. The Buddhist says the problem is desire and attachment. The Marxist says the problem is class struggle and economic exploitation. The Christian says the problem is human rebellion against the good Creator.

"What is the solution?" flows directly from your diagnosis of the problem. If the problem is oppressive structures, the solution is liberation and revolution. If the problem is moral decay, the solution is restoration of order and tradition. If the problem is human sin, the solution is forgiveness and new creation.

Finally, "What time is it?" asks where we are in the story. Are we in a golden age or a dark age? Are we progressing toward utopia or declining toward collapse? Are we waiting for a messiah or building the kingdom ourselves? The answer to this question determines whether we feel urgency or complacency, hope or despair.

Now here is what makes all of this so explosive in our current moment: most people have never consciously asked themselves these questions, yet they are acting out their answers in every choice they make, every policy they support, every protest they join or condemn.

The First-Century Jewish Story

To understand how the early Christians revolutionized the worldview of their time, we must first understand the worldview they inherited and transformed. The Jews of the first century were living inside a story with very specific answers to our five questions.

Who are we? We are the chosen people of the one true God (YHWH), the children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the ones through whom all the nations of the earth would be blessed. This was not ethnic pride in the modern sense. It was vocation. Israel existed not for herself but for the world.

Where are we? We are in the land that God promised to our ancestors, the place where heaven and earth meet, where God's presence dwells in the Temple. But we are also, in a deeper sense, still in exile. Yes, some of us returned from Babylon, but the great prophecies of restoration have not been fulfilled. We are ruled by pagans. The glory has not returned to the Temple. We are living in the wrong story, waiting for the right one to begin.

What has gone wrong? We have been unfaithful to the covenant. Our sins (and the sins of our ancestors) have brought judgment in the form of exile and foreign domination. But the real villain in the story is not just our own failure. It is the pagan empires that blaspheme God's name and oppress his people. It is the spiritual powers of darkness that hold the world in bondage.

What is the solution? God will act decisively to judge the wicked, vindicate the righteous, forgive his people, and establish his kingdom. The Messiah will come to defeat Israel's enemies, cleanse the Temple, and reign from Jerusalem. The Torah will go forth to the nations, and all peoples will stream to Zion to worship the one true God.

What time is it? It is late in the story, very late. The time of exile has stretched on far too long. Surely the promises are about to be fulfilled. Surely the kingdom is about to break in. We are on the very edge of the great reversal, when God will act to put the world to rights.

This was the worldview that shaped every aspect of Jewish life in the first century. It determined how they read their Scriptures, how they understood their suffering, how they resisted their Roman overlords, and how they recognized (or failed to recognize) what God was doing in their midst.

The Christian Revolution

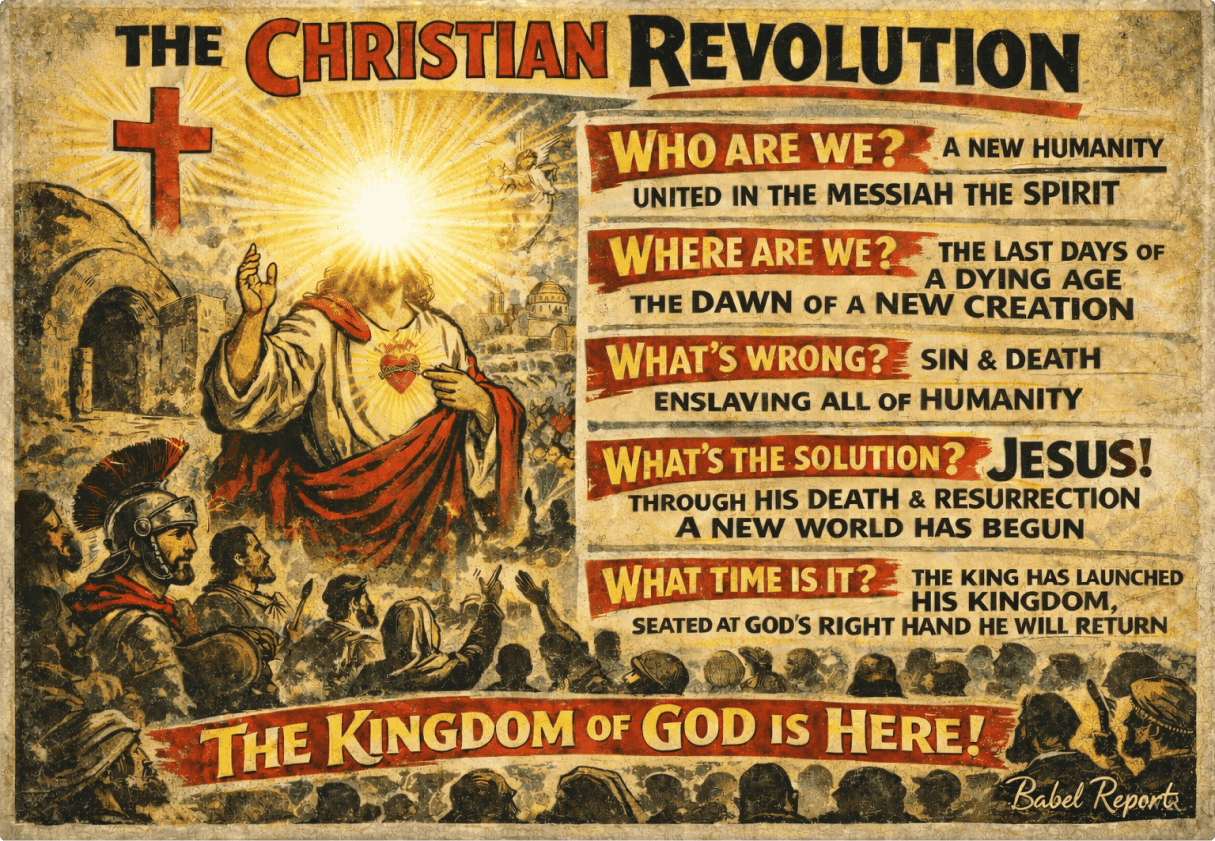

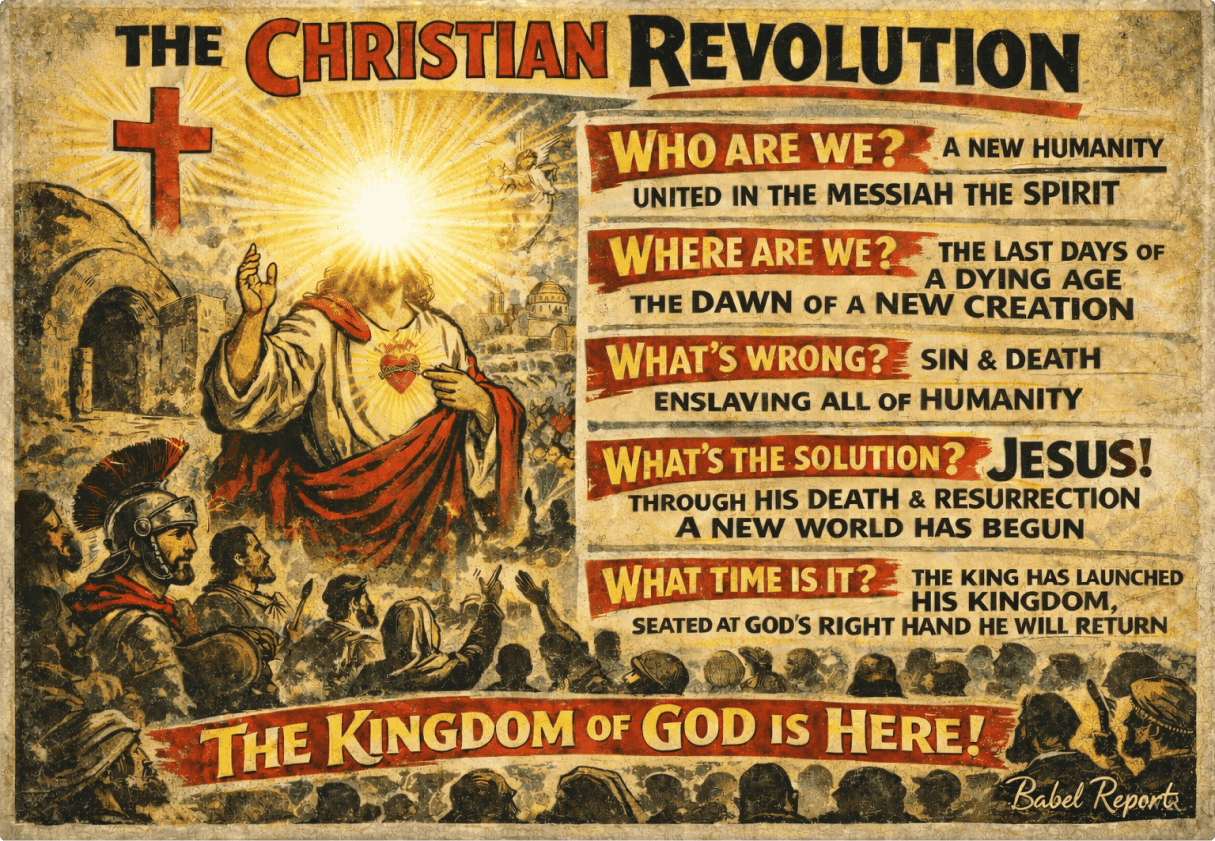

Now here is where things become truly extraordinary. The early followers of Jesus (YHWShA) did not simply adopt the Jewish worldview unchanged, nor did they abandon it for some Gentile alternative. They claimed that in Jesus, the God of Israel had done something so shocking, so unexpected, that it required every answer to be rewritten.

Who are we? We are still the people of the one true God, but now that identity is redefined around Jesus rather than Torah and Temple. Jew and Gentile together form a single family, a new humanity. We are not defined by ethnicity, social status, or gender, but by our incorporation into the Messiah through baptism and the gift of the Spirit. We are, as one early writer put it, a third race.

Where are we? We are still in the world that God created and called good, but we are also living in the overlap of two ages. The new creation has begun in Jesus' resurrection, but the old age has not yet fully passed away. We live in the time between the times, citizens of heaven dwelling temporarily in earthly cities, a colony of the future planted in the present.

What has gone wrong? Human rebellion against the Creator has unleashed the powers of sin and death into the world. These powers have enslaved not just Israel but all of humanity, corrupting every system, every institution, every heart. The problem is not simply bad laws or unjust rulers or even our own moral failures. The problem is cosmic, and it requires a cosmic solution.

What is the solution? God himself has entered into the broken world in the person of Jesus. Through his faithful life, his sacrificial death, and his bodily resurrection, Jesus has defeated the powers of sin and death, has taken the curse of exile upon himself, and has launched the new creation. The solution is not revolution from below but resurrection from above. God is making all things new, and he invites us to participate in that work through lives of justice, mercy, and faithfulness.

What time is it? It is the last days, the time of fulfillment, the age of the Spirit. The kingdom has been inaugurated but not yet consummated. The King has been enthroned at God's right hand and will return to complete what he has begun. We live in the mission window, the time of invitation, when the gospel goes out to all nations before the final day when God will judge the living and the dead and make all things new.

This was not simply a variation on the Jewish story. It was a radical reconfiguration of it. And when this story collided with the dominant worldviews of the Greco-Roman world, it produced not a synthesis but something entirely new. The early Christian communities were neither Jewish nor Gentile in the old sense, neither Roman nor barbarian, neither slave nor free. They were colonies of heaven living as signposts of the world to come.

The Invisible Lenses We All Wear

This mindset is the individual's particular variation on the parent worldview of the community to which they belong. Even if our hypothetical protester has never consciously articulated their aims, their real worldview can be seen clearly in the actions they perform, especially those instinctive habits they take for granted. This is because our choices are captured within a larger struggle, and as we make decisions, we align ourselves with one side of a great controversy or another.

We all inevitably interpret the information we receive through a grid of expectations, memories, and stories. In fact, if we could extract from anyone a complete answer to the question of what comes into their mind when they think about God or the ultimate nature of reality, we could predict with some certainty their spiritual and moral future. This worldview provides the stories through which we view all of reality, even when we are not aware we are telling them.

For the protester confronting an ICE agent, the question "What's wrong?" is currently the most urgent, and their action is itself the start of an implicit solution or campaign. They may be registering a subversive protest against a significant element of a dominant worldview without ever realizing they are actually acting out of a mutation within that very same system. We are like people born into a particular world order who find our lives framed in a dragnet of ideas we never personally invented.

Mapping Our Modern Worldviews

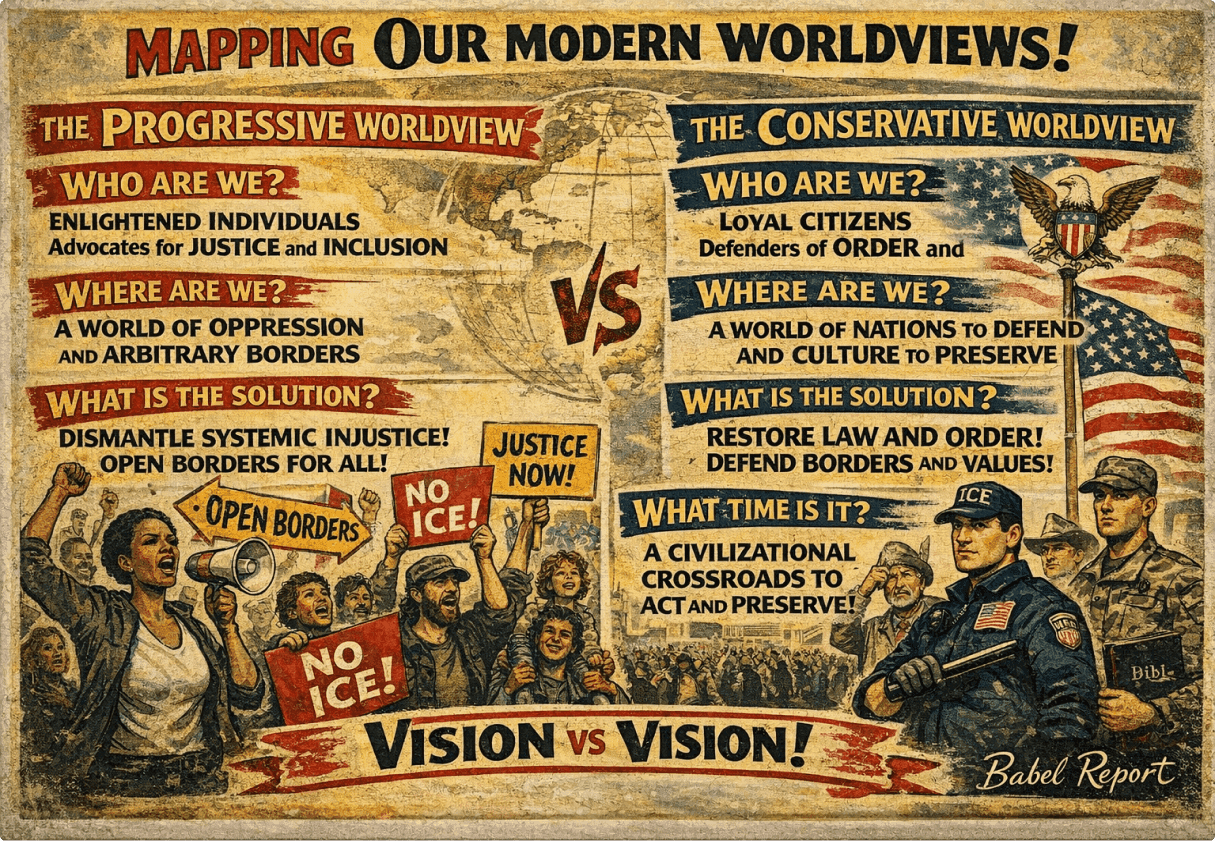

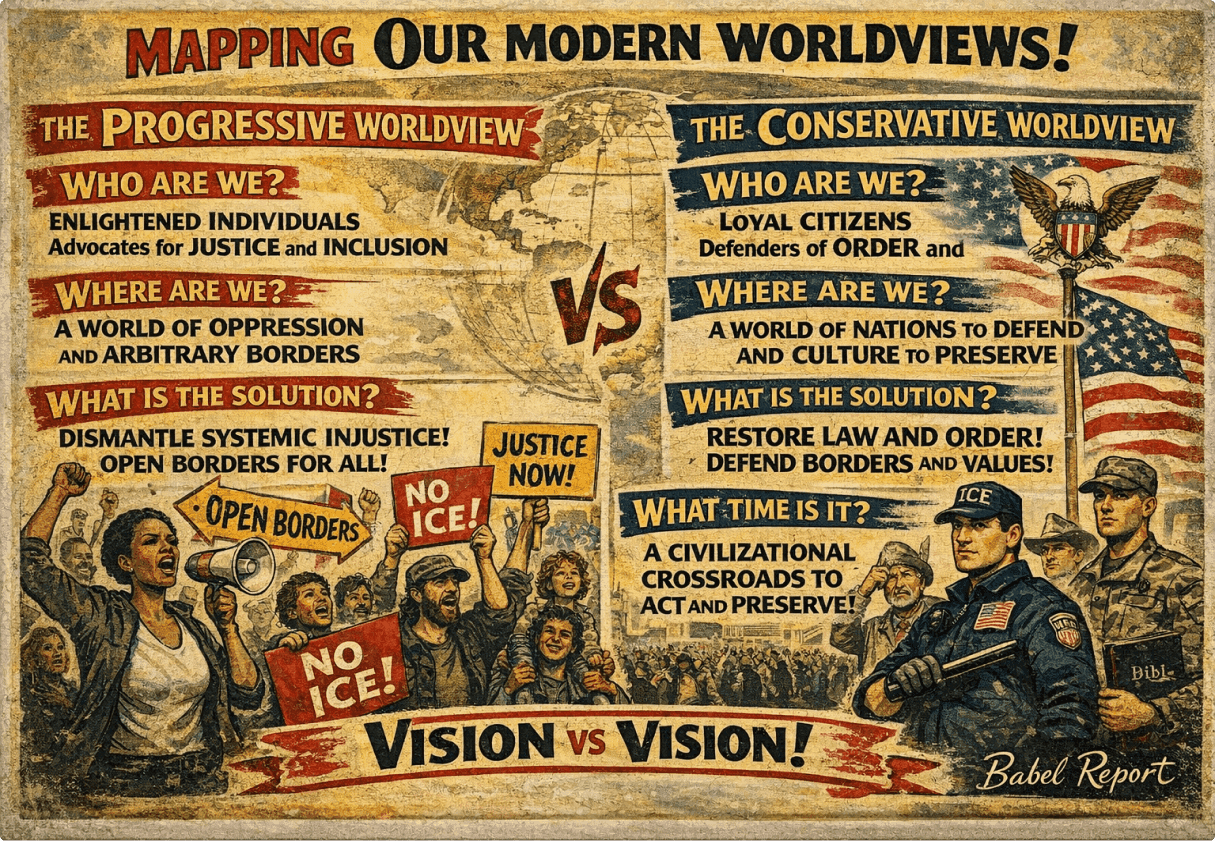

Now let us turn to the contemporary scene and attempt to map the worldviews at work in our immigration debates. I must offer a caveat here: what follows are not caricatures meant to mock but analytical frameworks meant to illuminate. Real people are always more complex than the worldviews they inhabit, but the worldviews themselves follow certain predictable patterns.

The Progressive Worldview

Who are we? We are enlightened individuals who have outgrown the tribal prejudices of the past. We recognize that all human beings have inherent dignity and worth regardless of where they were born or what documents they possess. Our identity is defined by our commitment to justice, inclusion, and the dismantling of oppressive systems.

Where are we? We are in a world of socially constructed boundaries and unjust hierarchies. National borders are arbitrary lines drawn by powerful people to exclude the vulnerable. The structures of law enforcement and immigration control are the latest iteration of systems designed to protect privilege and punish the poor.

What has gone wrong? The problem is systemic injustice. Throughout history, powerful groups have created laws, borders, and institutions to maintain their advantage at the expense of marginalized communities. Racism, xenophobia, and economic exploitation are not aberrations but features of the system. The immigration enforcement apparatus is simply the current face of state-sponsored violence against brown and black bodies.

What is the solution? The solution is liberation through the dismantling of oppressive structures. We must resist, protest, and refuse to cooperate with institutions that perpetuate injustice. We must create sanctuary spaces, open borders, and welcome the stranger without conditions. Justice demands radical hospitality and the redistribution of resources from those who have hoarded them to those who have been denied them.

What time is it? We are at a critical moment in the long arc of history that bends toward justice. We have made progress (the abolition of slavery, the civil rights movement, marriage equality), but that progress is fragile and under threat from reactionary forces. This is a time of urgency. If we do not act now, we risk sliding back into fascism, white supremacy, and authoritarian control.

The Conservative Worldview

Who are we? We are citizens of a nation founded on specific principles and held together by shared values, language, and law. Our identity is rooted in a particular history, a particular culture, and a particular covenant. We are stewards of something precious that was handed down to us, and we have a responsibility to preserve it and pass it on.

Where are we? We are in a world of real nations with real borders that exist for good reasons. Order, security, and the rule of law are not oppressive constructs but necessary foundations for human flourishing. A nation without borders is not a nation at all but a territory up for grabs. We are in a world where chaos constantly threatens to overwhelm civilization.

What has gone wrong? The problem is the breakdown of order and the abandonment of time-tested wisdom. When borders are not enforced, when laws are selectively applied, when traditions are mocked and discarded, society begins to fracture. The immigration crisis is not fundamentally about compassion versus cruelty. It is about whether we will maintain the structures that make compassion possible in the first place. Lawlessness, chaos, and the dissolution of national identity are the real threats.

What is the solution? The solution is the restoration and enforcement of law and order. We must secure our borders, enforce our immigration laws, and ensure that those who enter our country do so through proper legal channels. This is not cruelty but responsibility. A nation that cannot control its borders cannot protect its citizens, maintain its culture, or preserve its institutions. Compassion must be balanced with wisdom and prudence.

What time is it? We are at a dangerous crossroads. The great Western civilization that produced freedom, prosperity, and human dignity is under assault from both external threats and internal decay. If we do not act decisively to preserve what we have inherited, we risk losing it entirely. This is a time for courage and resolve, not naive idealism and sentimental compassion that will ultimately destroy the very society that makes such compassion possible.

The Clash of Controlling Narratives

Do you see it now? Both worldviews are internally coherent. Both answer all five questions in ways that make sense within their own frameworks. Both are pursuing what they genuinely believe to be justice. And yet they arrive at radically opposite conclusions about what should be done and who the heroes and villains are.

One side is living within a narrative of forced migration and rescue. Their story is one where the villain is the oppressive state and the hero is the one who offers hospitality and liberation to the refugee. To them, the acceptable year of the Lord means justice for the poor and the marginalized. They understand themselves as standing in the tradition of those who harbored escaped slaves, who sheltered Jews during the Holocaust, who resisted tyranny by protecting the vulnerable. The immigrant represents the neighbor in need, and the border agent represents a system that crushes the weak.

The other side is living within a narrative of order and vocation. Their story is about maintaining the moral and spiritual fabric of a society that they feel is under threat. They see the villain as chaos and the breakdown of the rule of law, which they believe is a God-given structure to prevent anarchy. For them, the border or the agent is a symbol of a house that must be kept secure against wicked spiritual forces that threaten their way of life. They see themselves as stewards of a covenant community, responsible for maintaining boundaries that preserve identity, safety, and shared values.

Both sides believe they are enacting the true story of justice. Both have cast themselves as the heroes and their opponents as villains. And herein lies the deepest layer of the problem: when two groups are living in fundamentally different narratives, they aren't merely disagreeing about the best policy response to a shared problem. They are disagreeing about what the problem even is, about what kind of world we live in, and about what story we are living inside.

The Power of Symbols

Symbols are everyday things that carry more-than-everyday meanings. An ICE agent's uniform or a border fence isn't just a piece of cloth or wire. It has become a symbol that sums up a whole way of life. For one group, that uniform is a symbol of state-sponsored violence and a text of terror. For the other, it is a symbol of peace and security, the very thing that prevents a city from becoming a wilderness.

When you lay a finger on a symbol, as I have said elsewhere, people react as if they have been struck in the ribs. This is why the debate isn't reasonable. It's visceral. It is a battle for the symbolic universe. To challenge the legitimacy of ICE (for one group) or to obstruct its agents (for the other) is not merely to question a policy. It is to threaten the entire architecture of meaning by which people organize their world.

Think of what happened when protestors tore down statues in recent years. The statues themselves were bronze and stone, but the outrage wasn't about the material. It was about what those statues represented. Some saw monuments to oppression that needed to be toppled. Others saw sacred markers of heritage and history under assault. Both responses were about symbolic meaning, not merely about metal and marble.

In the same way, the border agent carries symbolic weight far beyond his or her individual actions. The agent becomes a walking embodiment of either protection or oppression, liberation or captivity, depending entirely on which story you are living inside. It is only when the furniture is rearranged or the foundations are shaken that we are forced to take off our spectacles and examine the lenses through which we have been viewing God, the world, and ourselves.

The Idolatry of Ideology

One of the primary laws of human life is that you become like what you worship. In our world, the great ideologies (whether the myth of progress on the left or the myth of guaranteed security on the right) frequently take on an idolatrous status. When people give their total allegiance to a political movement, they define themselves in terms of it and treat those on the opposite side not as human beings made in the image of God, but as creditors, debtors, or pawns.

This leads to what we see on the news: a politics of the playground where reasoned discourse is replaced by an exchange of unreasoned emotions and emotional blackmail. Each side demonizes the other, casting their opponents as children of darkness or brute beasts while seeing themselves as angels. The language of good and evil, once reserved for theological categories, is now deployed with reckless abandon in the service of partisan tribalism.

Here is what troubles me most deeply. When individuals define themselves by their political preferences as if they were idols, they risk progressively ceasing to reflect the image of God and instead reflecting the harshness and exclusion of the systems they worship. You become what you bow down to. If your ultimate allegiance is to a political party or ideology, you will find yourself mirroring its spirit. If that spirit is one of division, accusation, and contempt, then that is what you will become, no matter how righteous your initial intentions.

The biblical writers understood this danger. They warned repeatedly that idols, though powerless in themselves, reshape the hearts of their worshipers. The prophet Isaiah put it starkly: those who make idols become like them, and so do all who trust in them. This is not merely ancient religious poetry. It is a profound insight into human psychology and spiritual formation.

The fact that these foundational commitments are normally buried does not mean they are not load-bearing. Indeed, part of the challenge of a genuinely human life (and certainly a life of Christian faith) is the renewal of the mind, which means learning how to think clearly about the way of life which is pleasing to God rather than being squeezed into the shape of the present age. Until we stop to consider these matters, we remain blind to the very things that move us.

A False Sense of Rightness

Both sides are often trying to establish their own righteousness, not in the sense of moral virtue, but in the sense of being in the right within their respective lawcourts. The American culture wars have created a package deal mentality where you are told you must tick one box and then tick all the others on that side of the page. This is the Procrustean bed of left and right, a relatively recent invention of the French Revolution, and it forces complex human realities into simplistic tribal categories.

For some, their religion consists of showing they are not unbelieving liberals. For others, it is showing they are not literalistic fundamentalists. In both cases, the truth is often reduced to the way I see it or the way it suits my power-claims, which is the essence of the postmodern problem. We have replaced the hard work of thinking things through with an epistemology of suspicion where every truth claim is assumed to be a veiled grab for control.

What you cannot do (not if you want to remain intellectually honest) is assume that ticking the boxes on your side of the ledger automatically places you on the side of the angels. The biblical story warns against precisely this kind of self-assured righteousness. Jesus told a parable about a Pharisee and a tax collector, both praying in the temple. The Pharisee thanked God that he was not like other people, especially not like that tax collector over there. The tax collector simply beat his breast and asked for mercy. Which one, Jesus asked, went home justified?

The same dynamic plays out today. We congratulate ourselves for not being like those people, whether those people are the bleeding-heart liberals who would dissolve all national boundaries or the heartless conservatives who would cage children at the border. We define our righteousness negatively, by what we are not, rather than positively, by what we actually embody.

What the Christian Worldview Offers Today

Ultimately, the heat you feel in these protests is the result of people searching for a secular version of original sin and a secular version of redemption. They are looking for a way to put the world to rights but are doing so using the enemy's weapons of hatred and division. One side says the problem is systemic injustice and the solution is radical hospitality. The other says the problem is moral chaos and the solution is restored order. Both are grasping for categories that actually come from the biblical story, even as they deny that story's authority.

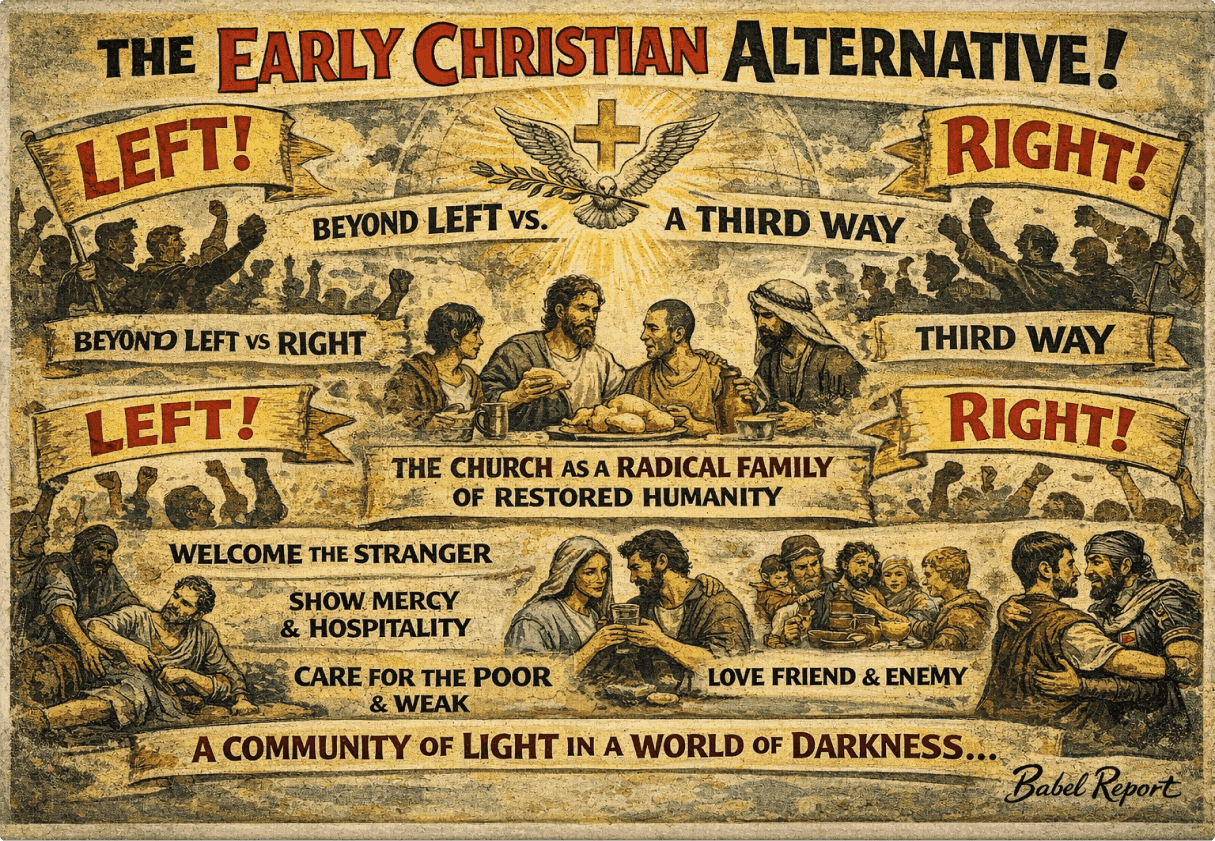

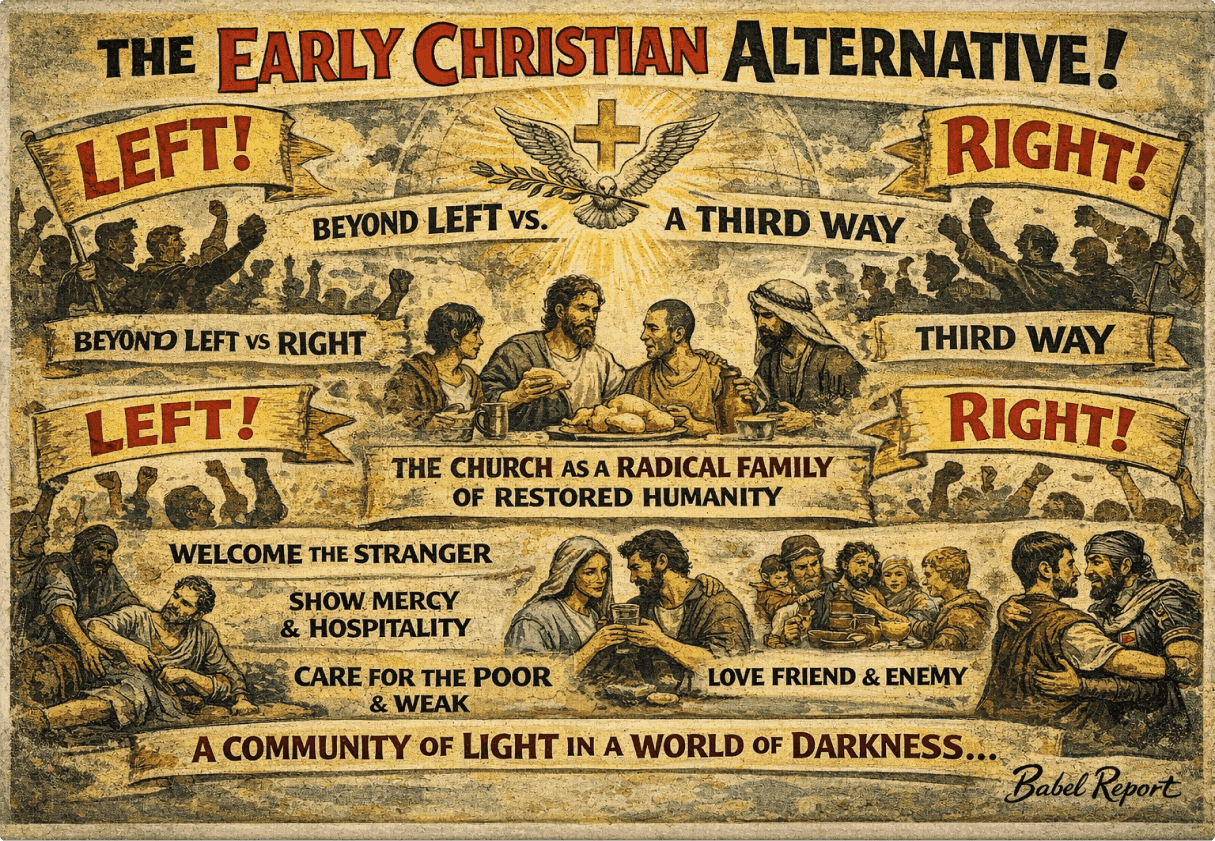

So what does the Christian worldview offer? Not a middle way that splits the difference, but a third way that challenges both.

Who are we? We are image-bearers of the Creator, every single one of us, regardless of nationality, documentation status, or any other human category. But we are also covenant people, those who have been called out of the nations to form a new nation, a royal priesthood, a holy people who belong to God. Our primary identity is not American or immigrant, citizen or alien, but members of the body of Christ. This does not erase other identities, but it relativizes them. When the church gathers, the immigrant and the ICE agent should both find themselves equally welcome at the same table, equally loved by the same God, equally challenged by the same gospel.

Where are we? We are in God's good creation, a world made to be the theater of his glory. But we are also in a world broken by sin, enslaved to powers that corrupt every human system and institution. National borders are neither sacred nor arbitrary. They are part of the furniture of a fallen world, sometimes necessary for order and sometimes tools of injustice. We must hold them with an open hand, neither absolutizing them nor dismissing them.

What has gone wrong? The problem is deeper than either side acknowledges. Yes, there are unjust systems that crush the vulnerable. Yes, there is moral chaos that threatens social order. But beneath both symptoms lies the root disease: human rebellion against the Creator. We have exchanged worship of the living God for worship of created things (whether those things are political ideologies, national identities, or utopian visions). The result is that we have become slaves to the very things we thought would liberate us.

What is the solution? The solution is not found in any political program, left or right. It is found in the death and resurrection of Jesus. God has entered into our broken world, taken the full weight of human sin and injustice upon himself, and opened up a way for new creation to break in. The solution is not revolution but resurrection. God is making all things new, and he invites us to participate in that renewal through lives of costly love, sacrificial service, and prophetic witness. This means we will sometimes stand with the vulnerable against the powerful, and sometimes we will stand for order against chaos. Wisdom is knowing which moment we are in.

What time is it? We are living in the overlap of the ages, in the time between Christ's resurrection and his return. The kingdom has broken into the world but has not yet fully come. We live in mission mode, as ambassadors of a coming King, as agents of reconciliation, as signposts pointing toward the world to come. This means we hold our political convictions with humility, knowing that no earthly kingdom perfectly reflects the kingdom of God. It also means we refuse the comfortable tribalism of left or right, insisting instead on a loyalty that transcends all human boundaries.

The Early Christian Alternative

The early Christians offered a different way: a community that ignored the normal ties of kinship or local identity to form a new family. This new family was supposed to be a standing rebuke to the powers, not by shouting them down, but by modeling a different kind of polis altogether. When the world sees Christians simply joining one of the two shouting crowds, it is a sign that the church has forgotten its own story and has started living in someone else's.

When Jesus told the story of the Good Samaritan, he was not giving a mild moral lesson about being nice to people. He was dramatically redefining the covenant boundary of who counts as a neighbor. The religious leader and the temple worker both passed by the wounded man, presumably to maintain their ritual purity. The Samaritan (the outsider, the theological enemy, the one who didn't belong) was the one who stopped. Think about that for a moment. The one who crossed the boundary was the one who fulfilled the law.

For the early Christians, the cross was the first visible sign that a new sort of family had been created, a third race that transcended all the boundary markers that normally divided humanity. Jews and Gentiles, slaves and free, male and female were being formed into a single body. This wasn't vague spiritual sentiment. It meant actual communities where actual people who would normally never share a meal were breaking bread together and calling each other brother and sister.

One early Christian document describes believers meeting in homes across the Roman Empire, sharing their possessions, caring for widows and orphans regardless of family ties, refusing to expose infants or participate in the gladiatorial games, treating slaves as equals in worship, and proclaiming a crucified criminal as Lord of the world. This was not a political program. It was a living demonstration of what the world looks like when God's future breaks into the present.

Living as resurrection people today means being justice-bringers who speak the truth to power, not by following the world's law of retaliation, but by seeking a restorative justice that aims to put the whole world back to rights. This is not soft-hearted sentimentalism. It is the hardest work imaginable, because it requires us to love our enemies, to pray for those who persecute us, to resist the comfortable categories of us versus them.

The Task Before Us

I have known Christians on both sides of the immigration debate, faithful people who read the same Scriptures and arrive at different policy conclusions. What troubles me is not the disagreement itself but the ease with which we baptize our political instincts and assume God is unambiguously on our team. The kingdom of heaven transcends the kingdoms of this world, which means it will always sit awkwardly with any human political arrangement.

Sometimes the kingdom will call us to protect the stranger. Sometimes it will call us to uphold order and law. Often it will call us to both simultaneously, which is why wisdom and discernment are so desperately needed. The question is not whether Christians should care about these issues. The question is whether we will care about them in a way that reflects the character of the God who called us.

When we get worked up about these issues, our task is to ensure our instincts are tuned not to the noise of the news media, but to the surprising hope of a God who is currently reconciling all creation to himself. This means we ask different questions than the world asks. Not just "What serves my interests?" but "What reflects the character of the God who made both the immigrant and the citizen?" Not just "What feels right to me?" but "What does justice look like when viewed from the cross?"

Here is the oddity we must face: both the harsh exclusion of the foreigner and the naive dissolution of all boundaries can miss the biblical vision. The biblical story is neither a manifesto for open borders nor a charter for fortress nations. It is something stranger and more demanding. It is the story of a God who chose one nation to be a light to all nations, who then in Jesus opened the covenant to the whole world, and who will one day gather people from every tribe and tongue and nation into a single city with open gates.

The Christian worldview offers something both sides desperately need but neither fully possesses: a coherent account of human dignity that doesn't dissolve into tribalism on one hand or radical individualism on the other. We can affirm the particular without absolutizing it. We can welcome the stranger without erasing all distinctions. We can uphold order without worshiping it. We can pursue justice without self-righteousness.

This is only possible because our ultimate allegiance is not to any earthly kingdom but to the King who was crucified by the powers of this world and raised by the power of God. When we stand at the foot of the cross, we see both the worst that human systems can do (executing an innocent man to preserve order) and the best that God can do (transforming that execution into the means of redemption). From that vantage point, we can neither worship the state nor demonize it, neither trust in revolution nor resign ourselves to the status quo.

Perhaps in a world so fractured and uncertain, that is precisely the story we need. Not a story that fits neatly into our political categories, but one that challenges all of them. Not a story that makes us comfortable in our tribes, but one that calls us out of them into a larger family. The invitation stands. The question is whether we have ears to hear it above the shouting.

When Border Debates Feel Like Holy War: What Your Worldview Has to Do with ICE Protests

When we find ourselves bewildered by the sheer intensity of contemporary political debates (whether it's protestors confronting Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents or the impassioned defense of such institutions from the other side) we are witnessing something far more significant than a policy disagreement. We are witnessing people who have touched upon one of the most vital mysteries of human existence: the fact that we are rarely the neutral observers we imagine ourselves to be. You see, a worldview is not something you normally look at, but rather the very thing you look through. Think of it like a pair of spectacles. We do not often notice the lenses themselves unless they become dirty or out of focus. Even the person we might call the protester, who perhaps acts out of a sudden, fiery conviction without ever sitting down to map out their metaphysics, is still standing on a deep and usually invisible foundation.

This is because worldviews are the basic stuff of human existence, the presuppositional and pre-cognitive stage of our culture and society. We all possess a kind of social autopilot or practical consciousness that directs our steps long before we stop to think about where they are leading us. Every philosophy, every political system, and indeed every single child, woman, and man has a view of the world, though most people simply take these for granted until something goes wrong.

Now, you see, the reason the situation with ICE protests feels as though it has the weight and heat of a religion is that, for many in our modern Western world, it effectively is one. We have been taught for two centuries, since the Enlightenment, that religion is a private hobby and politics is the public reality of how we run the world, but this is a shallow and misleading dualism. In the first century, as today, when you touch a political issue, you are reaching down into the deep, hidden foundations of the house people live in. You are touching their worldview.

When you see people on the American left protesting ICE agents, and those on the other side defending them with equal ferocity, you are witnessing a clash of symbolic universes and clashing stories. Let us break this down using the elements of a worldview to understand why regular people are getting so worked up.

The Skeleton of Every Worldview

Before we can understand the heat of these debates, we must first understand what a worldview actually is and how it functions. A worldview is the basic framework through which human beings organize all their experiences and knowledge. It provides the implicit answers to a handful of foundational questions that every human being, every culture, and every civilization must answer in one way or another.

These questions are not the sort one typically asks at dinner parties, but they are the questions that determine how we will respond when the dinner party is interrupted by a knock at the door. They are: Who are we? Where are we? What has gone wrong? What is the solution? And what time is it? These five questions form the skeleton upon which all our beliefs, values, and actions hang like flesh on bones.

Consider the question "Who are we?" A person might answer: We are autonomous individuals pursuing happiness. Or: We are members of a covenant community bound by sacred law. Or: We are evolved mammals competing for resources. Each answer leads to radically different conclusions about how we should live and what we should value.

The question "Where are we?" asks about the nature of the world itself. Is this a cosmos created by a good God, a neutral machine governed by impersonal laws, or a kind of illusion from which we need to escape? Your answer determines whether you see the material world as something to be enjoyed, exploited, or transcended.

"What has gone wrong?" is perhaps the most revealing question of all. Every worldview acknowledges that something is not as it should be. The secular progressive says the problem is oppressive structures and unjust systems. The traditional conservative says the problem is moral decay and the abandonment of time-tested wisdom. The Buddhist says the problem is desire and attachment. The Marxist says the problem is class struggle and economic exploitation. The Christian says the problem is human rebellion against the good Creator.

"What is the solution?" flows directly from your diagnosis of the problem. If the problem is oppressive structures, the solution is liberation and revolution. If the problem is moral decay, the solution is restoration of order and tradition. If the problem is human sin, the solution is forgiveness and new creation.

Finally, "What time is it?" asks where we are in the story. Are we in a golden age or a dark age? Are we progressing toward utopia or declining toward collapse? Are we waiting for a messiah or building the kingdom ourselves? The answer to this question determines whether we feel urgency or complacency, hope or despair.

Now here is what makes all of this so explosive in our current moment: most people have never consciously asked themselves these questions, yet they are acting out their answers in every choice they make, every policy they support, every protest they join or condemn.

The First-Century Jewish Story

To understand how the early Christians revolutionized the worldview of their time, we must first understand the worldview they inherited and transformed. The Jews of the first century were living inside a story with very specific answers to our five questions.

Who are we? We are the chosen people of the one true God (YHWH), the children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the ones through whom all the nations of the earth would be blessed. This was not ethnic pride in the modern sense. It was vocation. Israel existed not for herself but for the world.

Where are we? We are in the land that God promised to our ancestors, the place where heaven and earth meet, where God's presence dwells in the Temple. But we are also, in a deeper sense, still in exile. Yes, some of us returned from Babylon, but the great prophecies of restoration have not been fulfilled. We are ruled by pagans. The glory has not returned to the Temple. We are living in the wrong story, waiting for the right one to begin.

What has gone wrong? We have been unfaithful to the covenant. Our sins (and the sins of our ancestors) have brought judgment in the form of exile and foreign domination. But the real villain in the story is not just our own failure. It is the pagan empires that blaspheme God's name and oppress his people. It is the spiritual powers of darkness that hold the world in bondage.

What is the solution? God will act decisively to judge the wicked, vindicate the righteous, forgive his people, and establish his kingdom. The Messiah will come to defeat Israel's enemies, cleanse the Temple, and reign from Jerusalem. The Torah will go forth to the nations, and all peoples will stream to Zion to worship the one true God.

What time is it? It is late in the story, very late. The time of exile has stretched on far too long. Surely the promises are about to be fulfilled. Surely the kingdom is about to break in. We are on the very edge of the great reversal, when God will act to put the world to rights.

This was the worldview that shaped every aspect of Jewish life in the first century. It determined how they read their Scriptures, how they understood their suffering, how they resisted their Roman overlords, and how they recognized (or failed to recognize) what God was doing in their midst.

The Christian Revolution

Now here is where things become truly extraordinary. The early followers of Jesus (YHWShA) did not simply adopt the Jewish worldview unchanged, nor did they abandon it for some Gentile alternative. They claimed that in Jesus, the God of Israel had done something so shocking, so unexpected, that it required every answer to be rewritten.

Who are we? We are still the people of the one true God, but now that identity is redefined around Jesus rather than Torah and Temple. Jew and Gentile together form a single family, a new humanity. We are not defined by ethnicity, social status, or gender, but by our incorporation into the Messiah through baptism and the gift of the Spirit. We are, as one early writer put it, a third race.

Where are we? We are still in the world that God created and called good, but we are also living in the overlap of two ages. The new creation has begun in Jesus' resurrection, but the old age has not yet fully passed away. We live in the time between the times, citizens of heaven dwelling temporarily in earthly cities, a colony of the future planted in the present.

What has gone wrong? Human rebellion against the Creator has unleashed the powers of sin and death into the world. These powers have enslaved not just Israel but all of humanity, corrupting every system, every institution, every heart. The problem is not simply bad laws or unjust rulers or even our own moral failures. The problem is cosmic, and it requires a cosmic solution.

What is the solution? God himself has entered into the broken world in the person of Jesus. Through his faithful life, his sacrificial death, and his bodily resurrection, Jesus has defeated the powers of sin and death, has taken the curse of exile upon himself, and has launched the new creation. The solution is not revolution from below but resurrection from above. God is making all things new, and he invites us to participate in that work through lives of justice, mercy, and faithfulness.

What time is it? It is the last days, the time of fulfillment, the age of the Spirit. The kingdom has been inaugurated but not yet consummated. The King has been enthroned at God's right hand and will return to complete what he has begun. We live in the mission window, the time of invitation, when the gospel goes out to all nations before the final day when God will judge the living and the dead and make all things new.

This was not simply a variation on the Jewish story. It was a radical reconfiguration of it. And when this story collided with the dominant worldviews of the Greco-Roman world, it produced not a synthesis but something entirely new. The early Christian communities were neither Jewish nor Gentile in the old sense, neither Roman nor barbarian, neither slave nor free. They were colonies of heaven living as signposts of the world to come.

The Invisible Lenses We All Wear

This mindset is the individual's particular variation on the parent worldview of the community to which they belong. Even if our hypothetical protester has never consciously articulated their aims, their real worldview can be seen clearly in the actions they perform, especially those instinctive habits they take for granted. This is because our choices are captured within a larger struggle, and as we make decisions, we align ourselves with one side of a great controversy or another.

We all inevitably interpret the information we receive through a grid of expectations, memories, and stories. In fact, if we could extract from anyone a complete answer to the question of what comes into their mind when they think about God or the ultimate nature of reality, we could predict with some certainty their spiritual and moral future. This worldview provides the stories through which we view all of reality, even when we are not aware we are telling them.

For the protester confronting an ICE agent, the question "What's wrong?" is currently the most urgent, and their action is itself the start of an implicit solution or campaign. They may be registering a subversive protest against a significant element of a dominant worldview without ever realizing they are actually acting out of a mutation within that very same system. We are like people born into a particular world order who find our lives framed in a dragnet of ideas we never personally invented.

Mapping Our Modern Worldviews

Now let us turn to the contemporary scene and attempt to map the worldviews at work in our immigration debates. I must offer a caveat here: what follows are not caricatures meant to mock but analytical frameworks meant to illuminate. Real people are always more complex than the worldviews they inhabit, but the worldviews themselves follow certain predictable patterns.

The Progressive Worldview

Who are we? We are enlightened individuals who have outgrown the tribal prejudices of the past. We recognize that all human beings have inherent dignity and worth regardless of where they were born or what documents they possess. Our identity is defined by our commitment to justice, inclusion, and the dismantling of oppressive systems.

Where are we? We are in a world of socially constructed boundaries and unjust hierarchies. National borders are arbitrary lines drawn by powerful people to exclude the vulnerable. The structures of law enforcement and immigration control are the latest iteration of systems designed to protect privilege and punish the poor.

What has gone wrong? The problem is systemic injustice. Throughout history, powerful groups have created laws, borders, and institutions to maintain their advantage at the expense of marginalized communities. Racism, xenophobia, and economic exploitation are not aberrations but features of the system. The immigration enforcement apparatus is simply the current face of state-sponsored violence against brown and black bodies.

What is the solution? The solution is liberation through the dismantling of oppressive structures. We must resist, protest, and refuse to cooperate with institutions that perpetuate injustice. We must create sanctuary spaces, open borders, and welcome the stranger without conditions. Justice demands radical hospitality and the redistribution of resources from those who have hoarded them to those who have been denied them.

What time is it? We are at a critical moment in the long arc of history that bends toward justice. We have made progress (the abolition of slavery, the civil rights movement, marriage equality), but that progress is fragile and under threat from reactionary forces. This is a time of urgency. If we do not act now, we risk sliding back into fascism, white supremacy, and authoritarian control.

The Conservative Worldview

Who are we? We are citizens of a nation founded on specific principles and held together by shared values, language, and law. Our identity is rooted in a particular history, a particular culture, and a particular covenant. We are stewards of something precious that was handed down to us, and we have a responsibility to preserve it and pass it on.

Where are we? We are in a world of real nations with real borders that exist for good reasons. Order, security, and the rule of law are not oppressive constructs but necessary foundations for human flourishing. A nation without borders is not a nation at all but a territory up for grabs. We are in a world where chaos constantly threatens to overwhelm civilization.

What has gone wrong? The problem is the breakdown of order and the abandonment of time-tested wisdom. When borders are not enforced, when laws are selectively applied, when traditions are mocked and discarded, society begins to fracture. The immigration crisis is not fundamentally about compassion versus cruelty. It is about whether we will maintain the structures that make compassion possible in the first place. Lawlessness, chaos, and the dissolution of national identity are the real threats.

What is the solution? The solution is the restoration and enforcement of law and order. We must secure our borders, enforce our immigration laws, and ensure that those who enter our country do so through proper legal channels. This is not cruelty but responsibility. A nation that cannot control its borders cannot protect its citizens, maintain its culture, or preserve its institutions. Compassion must be balanced with wisdom and prudence.

What time is it? We are at a dangerous crossroads. The great Western civilization that produced freedom, prosperity, and human dignity is under assault from both external threats and internal decay. If we do not act decisively to preserve what we have inherited, we risk losing it entirely. This is a time for courage and resolve, not naive idealism and sentimental compassion that will ultimately destroy the very society that makes such compassion possible.

The Clash of Controlling Narratives

Do you see it now? Both worldviews are internally coherent. Both answer all five questions in ways that make sense within their own frameworks. Both are pursuing what they genuinely believe to be justice. And yet they arrive at radically opposite conclusions about what should be done and who the heroes and villains are.

One side is living within a narrative of forced migration and rescue. Their story is one where the villain is the oppressive state and the hero is the one who offers hospitality and liberation to the refugee. To them, the acceptable year of the Lord means justice for the poor and the marginalized. They understand themselves as standing in the tradition of those who harbored escaped slaves, who sheltered Jews during the Holocaust, who resisted tyranny by protecting the vulnerable. The immigrant represents the neighbor in need, and the border agent represents a system that crushes the weak.

The other side is living within a narrative of order and vocation. Their story is about maintaining the moral and spiritual fabric of a society that they feel is under threat. They see the villain as chaos and the breakdown of the rule of law, which they believe is a God-given structure to prevent anarchy. For them, the border or the agent is a symbol of a house that must be kept secure against wicked spiritual forces that threaten their way of life. They see themselves as stewards of a covenant community, responsible for maintaining boundaries that preserve identity, safety, and shared values.

Both sides believe they are enacting the true story of justice. Both have cast themselves as the heroes and their opponents as villains. And herein lies the deepest layer of the problem: when two groups are living in fundamentally different narratives, they aren't merely disagreeing about the best policy response to a shared problem. They are disagreeing about what the problem even is, about what kind of world we live in, and about what story we are living inside.

The Power of Symbols

Symbols are everyday things that carry more-than-everyday meanings. An ICE agent's uniform or a border fence isn't just a piece of cloth or wire. It has become a symbol that sums up a whole way of life. For one group, that uniform is a symbol of state-sponsored violence and a text of terror. For the other, it is a symbol of peace and security, the very thing that prevents a city from becoming a wilderness.

When you lay a finger on a symbol, as I have said elsewhere, people react as if they have been struck in the ribs. This is why the debate isn't reasonable. It's visceral. It is a battle for the symbolic universe. To challenge the legitimacy of ICE (for one group) or to obstruct its agents (for the other) is not merely to question a policy. It is to threaten the entire architecture of meaning by which people organize their world.

Think of what happened when protestors tore down statues in recent years. The statues themselves were bronze and stone, but the outrage wasn't about the material. It was about what those statues represented. Some saw monuments to oppression that needed to be toppled. Others saw sacred markers of heritage and history under assault. Both responses were about symbolic meaning, not merely about metal and marble.

In the same way, the border agent carries symbolic weight far beyond his or her individual actions. The agent becomes a walking embodiment of either protection or oppression, liberation or captivity, depending entirely on which story you are living inside. It is only when the furniture is rearranged or the foundations are shaken that we are forced to take off our spectacles and examine the lenses through which we have been viewing God, the world, and ourselves.

The Idolatry of Ideology

One of the primary laws of human life is that you become like what you worship. In our world, the great ideologies (whether the myth of progress on the left or the myth of guaranteed security on the right) frequently take on an idolatrous status. When people give their total allegiance to a political movement, they define themselves in terms of it and treat those on the opposite side not as human beings made in the image of God, but as creditors, debtors, or pawns.

This leads to what we see on the news: a politics of the playground where reasoned discourse is replaced by an exchange of unreasoned emotions and emotional blackmail. Each side demonizes the other, casting their opponents as children of darkness or brute beasts while seeing themselves as angels. The language of good and evil, once reserved for theological categories, is now deployed with reckless abandon in the service of partisan tribalism.

Here is what troubles me most deeply. When individuals define themselves by their political preferences as if they were idols, they risk progressively ceasing to reflect the image of God and instead reflecting the harshness and exclusion of the systems they worship. You become what you bow down to. If your ultimate allegiance is to a political party or ideology, you will find yourself mirroring its spirit. If that spirit is one of division, accusation, and contempt, then that is what you will become, no matter how righteous your initial intentions.

The biblical writers understood this danger. They warned repeatedly that idols, though powerless in themselves, reshape the hearts of their worshipers. The prophet Isaiah put it starkly: those who make idols become like them, and so do all who trust in them. This is not merely ancient religious poetry. It is a profound insight into human psychology and spiritual formation.

The fact that these foundational commitments are normally buried does not mean they are not load-bearing. Indeed, part of the challenge of a genuinely human life (and certainly a life of Christian faith) is the renewal of the mind, which means learning how to think clearly about the way of life which is pleasing to God rather than being squeezed into the shape of the present age. Until we stop to consider these matters, we remain blind to the very things that move us.

A False Sense of Rightness

Both sides are often trying to establish their own righteousness, not in the sense of moral virtue, but in the sense of being in the right within their respective lawcourts. The American culture wars have created a package deal mentality where you are told you must tick one box and then tick all the others on that side of the page. This is the Procrustean bed of left and right, a relatively recent invention of the French Revolution, and it forces complex human realities into simplistic tribal categories.

For some, their religion consists of showing they are not unbelieving liberals. For others, it is showing they are not literalistic fundamentalists. In both cases, the truth is often reduced to the way I see it or the way it suits my power-claims, which is the essence of the postmodern problem. We have replaced the hard work of thinking things through with an epistemology of suspicion where every truth claim is assumed to be a veiled grab for control.

What you cannot do (not if you want to remain intellectually honest) is assume that ticking the boxes on your side of the ledger automatically places you on the side of the angels. The biblical story warns against precisely this kind of self-assured righteousness. Jesus told a parable about a Pharisee and a tax collector, both praying in the temple. The Pharisee thanked God that he was not like other people, especially not like that tax collector over there. The tax collector simply beat his breast and asked for mercy. Which one, Jesus asked, went home justified?

The same dynamic plays out today. We congratulate ourselves for not being like those people, whether those people are the bleeding-heart liberals who would dissolve all national boundaries or the heartless conservatives who would cage children at the border. We define our righteousness negatively, by what we are not, rather than positively, by what we actually embody.

What the Christian Worldview Offers Today

Ultimately, the heat you feel in these protests is the result of people searching for a secular version of original sin and a secular version of redemption. They are looking for a way to put the world to rights but are doing so using the enemy's weapons of hatred and division. One side says the problem is systemic injustice and the solution is radical hospitality. The other says the problem is moral chaos and the solution is restored order. Both are grasping for categories that actually come from the biblical story, even as they deny that story's authority.

So what does the Christian worldview offer? Not a middle way that splits the difference, but a third way that challenges both.

Who are we? We are image-bearers of the Creator, every single one of us, regardless of nationality, documentation status, or any other human category. But we are also covenant people, those who have been called out of the nations to form a new nation, a royal priesthood, a holy people who belong to God. Our primary identity is not American or immigrant, citizen or alien, but members of the body of Christ. This does not erase other identities, but it relativizes them. When the church gathers, the immigrant and the ICE agent should both find themselves equally welcome at the same table, equally loved by the same God, equally challenged by the same gospel.

Where are we? We are in God's good creation, a world made to be the theater of his glory. But we are also in a world broken by sin, enslaved to powers that corrupt every human system and institution. National borders are neither sacred nor arbitrary. They are part of the furniture of a fallen world, sometimes necessary for order and sometimes tools of injustice. We must hold them with an open hand, neither absolutizing them nor dismissing them.

What has gone wrong? The problem is deeper than either side acknowledges. Yes, there are unjust systems that crush the vulnerable. Yes, there is moral chaos that threatens social order. But beneath both symptoms lies the root disease: human rebellion against the Creator. We have exchanged worship of the living God for worship of created things (whether those things are political ideologies, national identities, or utopian visions). The result is that we have become slaves to the very things we thought would liberate us.

What is the solution? The solution is not found in any political program, left or right. It is found in the death and resurrection of Jesus. God has entered into our broken world, taken the full weight of human sin and injustice upon himself, and opened up a way for new creation to break in. The solution is not revolution but resurrection. God is making all things new, and he invites us to participate in that renewal through lives of costly love, sacrificial service, and prophetic witness. This means we will sometimes stand with the vulnerable against the powerful, and sometimes we will stand for order against chaos. Wisdom is knowing which moment we are in.

What time is it? We are living in the overlap of the ages, in the time between Christ's resurrection and his return. The kingdom has broken into the world but has not yet fully come. We live in mission mode, as ambassadors of a coming King, as agents of reconciliation, as signposts pointing toward the world to come. This means we hold our political convictions with humility, knowing that no earthly kingdom perfectly reflects the kingdom of God. It also means we refuse the comfortable tribalism of left or right, insisting instead on a loyalty that transcends all human boundaries.

The Early Christian Alternative

The early Christians offered a different way: a community that ignored the normal ties of kinship or local identity to form a new family. This new family was supposed to be a standing rebuke to the powers, not by shouting them down, but by modeling a different kind of polis altogether. When the world sees Christians simply joining one of the two shouting crowds, it is a sign that the church has forgotten its own story and has started living in someone else's.

When Jesus told the story of the Good Samaritan, he was not giving a mild moral lesson about being nice to people. He was dramatically redefining the covenant boundary of who counts as a neighbor. The religious leader and the temple worker both passed by the wounded man, presumably to maintain their ritual purity. The Samaritan (the outsider, the theological enemy, the one who didn't belong) was the one who stopped. Think about that for a moment. The one who crossed the boundary was the one who fulfilled the law.

For the early Christians, the cross was the first visible sign that a new sort of family had been created, a third race that transcended all the boundary markers that normally divided humanity. Jews and Gentiles, slaves and free, male and female were being formed into a single body. This wasn't vague spiritual sentiment. It meant actual communities where actual people who would normally never share a meal were breaking bread together and calling each other brother and sister.

One early Christian document describes believers meeting in homes across the Roman Empire, sharing their possessions, caring for widows and orphans regardless of family ties, refusing to expose infants or participate in the gladiatorial games, treating slaves as equals in worship, and proclaiming a crucified criminal as Lord of the world. This was not a political program. It was a living demonstration of what the world looks like when God's future breaks into the present.

Living as resurrection people today means being justice-bringers who speak the truth to power, not by following the world's law of retaliation, but by seeking a restorative justice that aims to put the whole world back to rights. This is not soft-hearted sentimentalism. It is the hardest work imaginable, because it requires us to love our enemies, to pray for those who persecute us, to resist the comfortable categories of us versus them.

The Task Before Us

I have known Christians on both sides of the immigration debate, faithful people who read the same Scriptures and arrive at different policy conclusions. What troubles me is not the disagreement itself but the ease with which we baptize our political instincts and assume God is unambiguously on our team. The kingdom of heaven transcends the kingdoms of this world, which means it will always sit awkwardly with any human political arrangement.

Sometimes the kingdom will call us to protect the stranger. Sometimes it will call us to uphold order and law. Often it will call us to both simultaneously, which is why wisdom and discernment are so desperately needed. The question is not whether Christians should care about these issues. The question is whether we will care about them in a way that reflects the character of the God who called us.

When we get worked up about these issues, our task is to ensure our instincts are tuned not to the noise of the news media, but to the surprising hope of a God who is currently reconciling all creation to himself. This means we ask different questions than the world asks. Not just "What serves my interests?" but "What reflects the character of the God who made both the immigrant and the citizen?" Not just "What feels right to me?" but "What does justice look like when viewed from the cross?"

Here is the oddity we must face: both the harsh exclusion of the foreigner and the naive dissolution of all boundaries can miss the biblical vision. The biblical story is neither a manifesto for open borders nor a charter for fortress nations. It is something stranger and more demanding. It is the story of a God who chose one nation to be a light to all nations, who then in Jesus opened the covenant to the whole world, and who will one day gather people from every tribe and tongue and nation into a single city with open gates.

The Christian worldview offers something both sides desperately need but neither fully possesses: a coherent account of human dignity that doesn't dissolve into tribalism on one hand or radical individualism on the other. We can affirm the particular without absolutizing it. We can welcome the stranger without erasing all distinctions. We can uphold order without worshiping it. We can pursue justice without self-righteousness.

This is only possible because our ultimate allegiance is not to any earthly kingdom but to the King who was crucified by the powers of this world and raised by the power of God. When we stand at the foot of the cross, we see both the worst that human systems can do (executing an innocent man to preserve order) and the best that God can do (transforming that execution into the means of redemption). From that vantage point, we can neither worship the state nor demonize it, neither trust in revolution nor resign ourselves to the status quo.

Perhaps in a world so fractured and uncertain, that is precisely the story we need. Not a story that fits neatly into our political categories, but one that challenges all of them. Not a story that makes us comfortable in our tribes, but one that calls us out of them into a larger family. The invitation stands. The question is whether we have ears to hear it above the shouting.

EXPLORE MORE

Death Isn't Natural

Nobody eulogizes their dog like they eulogize grandma. Why does human death hit different? Maybe because we were never meant to die.

LEARN MORE

The Money God

Wealth promises security but demands worship. Mammon, the ancient money-god, still enslaves. Jesus offers freedom through resurrection faith.

LEARN MORE

The Pastor's Palace

From Eden, the temple, and the Kingdom of God. We are the new temple God wants to dwell in, not buildings made by hands.

LEARN MORE

EXPLORE MORE

Death Isn't Natural

Nobody eulogizes their dog like they eulogize grandma. Why does human death hit different? Maybe because we were never meant to die.

LEARN MORE

The Money God

Wealth promises security but demands worship. Mammon, the ancient money-god, still enslaves. Jesus offers freedom through resurrection faith.

LEARN MORE

The Pastor's Palace

From Eden, the temple, and the Kingdom of God. We are the new temple God wants to dwell in, not buildings made by hands.

LEARN MORE

EXPLORE MORE

Death Isn't Natural

Nobody eulogizes their dog like they eulogize grandma. Why does human death hit different? Maybe because we were never meant to die.

LEARN MORE

The Money God

Wealth promises security but demands worship. Mammon, the ancient money-god, still enslaves. Jesus offers freedom through resurrection faith.

LEARN MORE

The Pastor's Palace

From Eden, the temple, and the Kingdom of God. We are the new temple God wants to dwell in, not buildings made by hands.

LEARN MORE