Lord, Who Are You?

Lord, Who Are You?

When Paul Said "Lord," Did He Mean YHWH?

Here's an odd thing. Ask most Christians what happened on the Damascus Road, and they'll tell you Paul met Jesus (YHWShA). Ask them what Paul's first words were, and they'll say something like, "Who are you, sir?" The word "Lord" gets heard as a polite form of address, the kind of thing you might say to a stranger who's just startled you on the street.

But that reading, however natural it feels in English, tells us more about our cultural instincts than about Paul's world. And if we're going to understand what actually happened in that moment, we need to step back into the mental furniture of a first-century Pharisee, trained in Scripture, steeped in synagogue life, praying the Shema every morning and evening.

When we do that, a rather different picture emerges.

The Language Paul Breathed

Paul didn't invent his religious vocabulary on the Damascus Road. He inherited it. As a Pharisee, he had been shaped by Israel's Scriptures in both their Hebrew form and their Greek translation, the Septuagint. This matters more than we might first imagine.

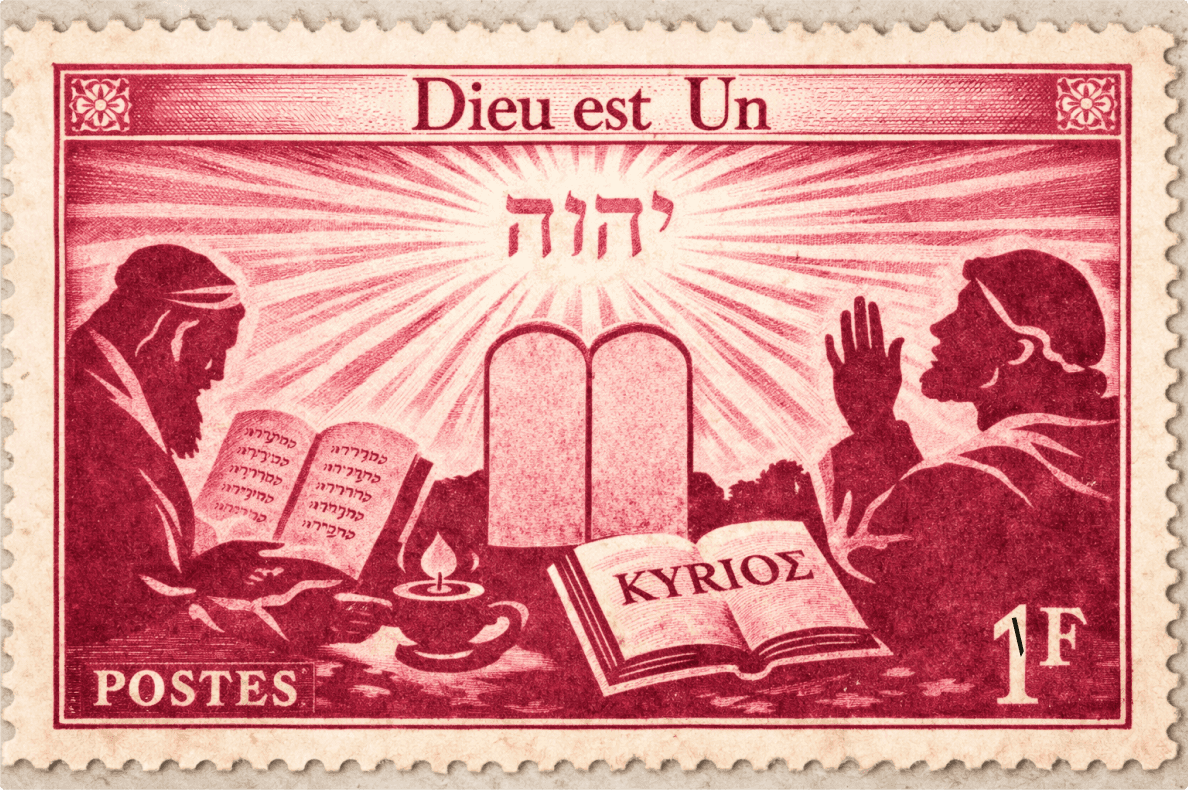

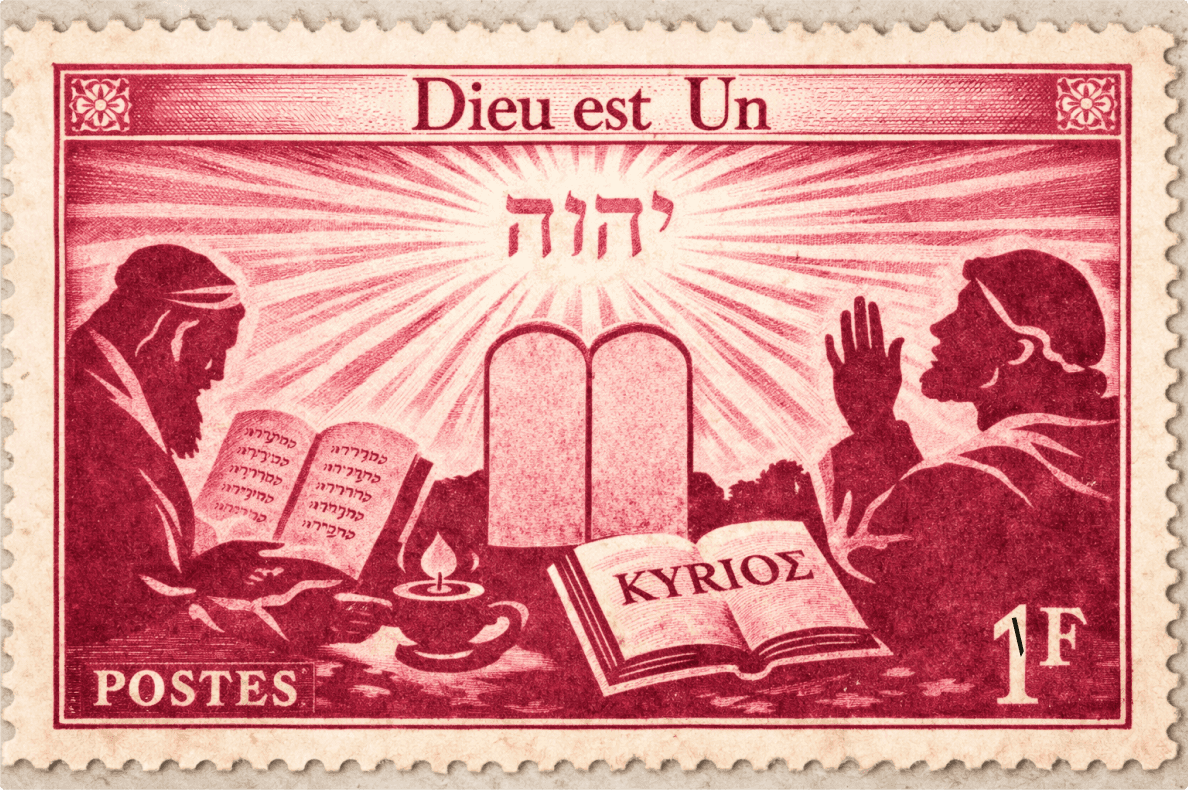

In Greek-speaking Jewish communities, the Divine Name (YHWH) was not pronounced. When the text read יהוה, the reader spoke aloud kyrios, "Lord." Over time, this wasn't just a reading convention. It became the standard way Greek-speaking Jews referred to and addressed the God (YHWH) of Israel. Not a vague honorific. A reverent substitute for the Name itself.

There was a seminary student once who asked whether Paul might have meant "sir" when he said kyrios on the road to Damascus. The professor responded with a simple challenge: "Show me one instance in Jewish literature where someone addresses an unidentified heavenly voice as 'sir.'" The student couldn't. None of the class could. That's the problem.

When Paul used kyrios in the presence of what appeared to be a divine manifestation, he wasn't reaching for a neutral term. He was using the language he had always used for Israel's God.

The Pattern of Encounter

The story itself follows a script that runs throughout Israel's Scriptures. A divine presence appears, often accompanied by overwhelming light or fire. A human being is struck with fear or physically incapacitated. The human addresses the presence as the God of Israel. Only then does fuller revelation come.

Moses at the burning bush. Isaiah in the temple. Ezekiel by the river. In the Hebrew text, these figures likely addressed YHWH directly, speaking the Name itself. But something changed during and after the Babylonian exile. Whether out of heightened reverence, protective instinct, or deepening interpretation of the third commandment, Jewish communities began to avoid pronouncing the Divine Name. Instead, they substituted Adonai when reading aloud.

This wasn't a casual shift. It reflected Israel's post-exilic wrestling with holiness, identity, and how to guard what was most sacred after everything had been lost and then partially restored.

By the first century, this practice had become standard, especially in Greek-speaking Jewish communities. When scribes translated the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek, the Septuagint, they rendered YHWH as kyrios, "Lord." And when Paul read Isaiah's vision, he read Isaiah crying out, "Kyrios of hosts!" When he read Moses at the bush, he read Moses asking, "Who shall I say sent me, Kyrios?"

So when Paul encountered a blinding light and a voice from heaven, his scriptural reflexes (trained on the Greek text and centuries of post-exilic reverence) would have reached for kyrios as the natural way to address the God of Israel in a theophany. Not because Moses said it that way, but because Paul's Bible and his liturgical practice taught him to say it that way.

That's the point. The pattern of divine encounter was ancient. But Paul's linguistic response to it was shaped by his Septuagint-saturated, post-exilic Jewish world.

Why "Sir" Simply Won't Work

Of course, one can argue for the polite reading. Many thoughtful people do. But the argument collapses under its own weight when you press on it.

First, the circumstances. This isn't someone tapping Paul on the shoulder at the marketplace. He's surrounded by heavenly light and struck blind. Second, Jewish usage. Greek-speaking Jews didn't casually sprinkle kyrios into conversations with mysterious voices from above. Third, the biblical pattern. Every comparable narrative of divine encounter involves an address to the God of Israel before the revelation of identity, not after.

What you cannot do, not if you want to remain consistent with the evidence, is read Paul's response as if he were speaking to a stranger on the street. The cultural and literary context simply doesn't support it.

What Paul Did Next

Here's where the argument becomes even stronger. If Paul later believed he had mistakenly addressed Jesus as YHWH, we would expect some clarification, wouldn't we? Some careful explanation in his letters. "I thought at first it was God himself, but of course I came to understand it was the Messiah, acting on God's behalf."

We get nothing of the kind.

Instead, Paul's theology moves decisively in the opposite direction. He takes passages about YHWH and applies them directly to Jesus. Not carefully. Not apologetically. Directly.

Joel promises that "everyone who calls on the name of YHWH will be saved." Paul applies that to calling on Jesus. Isaiah declares that every knee will bow to YHWH alone. Paul applies that to Jesus. These aren't casual proof texts. They're some of Israel's most fiercely monotheistic declarations. Paul knew Isaiah insisted, "I am YHWH, and there is no other." And yet he places Jesus right there, within that exclusive identity.

This only makes sense if Paul believed that the one he encountered on the Damascus Road was not a lesser agent of God, but God himself revealed in and as Jesus.

Rewriting the Shema

The most revealing move comes in 1 Corinthians 8:6. There, Paul does something no Torah-faithful Jew would dare attempt without direct revelation. He reformulates Israel's central confession.

"There is one God, the Father," he writes, "and one Lord, Jesus Messiah."

If we were to render Paul's theological logic back into Hebrew, using the Divine Name as his Greek "Lord" implies, it would read something like this:

אלהים אחד האב ויהוה אחד יהושע המשיח

Alohim echad ha-Av, ve-YHWH echad Yahusha ha-Mashiach

Or in English, preserving the Divine Name:

"One God, the Father, and one YHWH, Jesus (Yahusha) the Messiah."

Read that again slowly. Paul isn't adding a second god alongside YHWH. He's placing Jesus inside the identity of YHWH himself. This isn't the introduction of a second god. It's the deliberate placement of Jesus inside the confession of Israel's one God.

Think of it this way. John tells us that "the Word became flesh and dwelt among us" (John 1:14). That word dwelt is eskēnōsen in Greek, which literally means "tabernacled." John is saying that in Jesus, YHWH did what he promised in the wilderness and in the temple: he came to dwell with his people. Not through a tent or a building this time, but in human flesh.

Paul says something similar when he writes of "God manifest in the flesh" (1 Timothy 3:16). This is the mystery the early Christians confessed. The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the one who led Israel through the wilderness, the one whose glory filled the temple, had now tabernacled among his people in a new and final way.

The word "Lord" here is doing exactly what it did in the synagogue, standing in for the Divine Name. Paul is saying, in effect, that the identity of YHWH now includes both the Father and Jesus the Messiah.

I grew up in a Catholic household where the Trinity was a settled fact, something you learned from the catechism and didn't question. Later, in Oneness Pentecostal circles, I heard passionate sermons about Jesus being Lord, about the Name, about the fullness of the Godhead dwelling bodily. But it took reading Paul in his own world to realize what a staggering claim this was. Paul wasn't softening Jewish monotheism. He was reshaping it from the inside out, and he was doing so because of what happened on that road.

The Name Above Every Name

And Paul's claim goes even further. When he writes to the Philippians that God gave Jesus "the name above every name," so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow (Philippians 2:9-11), he isn't speaking of a new title or honorary designation. He's claiming Jesus bears the Name itself.

This is where the pieces lock together. Isaiah declared that to YHWH alone every knee will bow and every tongue confess. Paul takes that uncompromising monotheistic statement and applies it to Jesus without qualification. The name above every name isn't "Lord" as a generic honorific. It's the Name that "Lord" stood in for, the Tetragrammaton itself, YHWH, the name Jews spoke as kyrios out of reverence but understood as the unique identity of Israel's God.

Think of it this way. Israel's Scriptures spoke of YHWH's Name dwelling in the temple, going before the people in the wilderness, carrying divine authority and presence. The Name wasn't a label. It was a way of talking about God's active presence in the world. When Paul says Jesus bears the name above every name, he's not adding Jesus to a pantheon. He's identifying Jesus as the embodied presence of YHWH himself.

This is the logic of the Damascus Road worked out in Paul's theology. The voice that identified itself as Jesus was the same voice Paul addressed as kyrios, the same presence Isaiah saw high and lifted up, the same God before whom every knee must bow.

The Logic of the Moment

Put it all together and the logic becomes inescapable. Paul encountered a divine presence. He addressed that presence as kyrios, meaning the God of Israel. The voice revealed itself as Jesus. Paul did not conclude that he had been mistaken about encountering God. He concluded that Jesus belonged within the identity of Israel's God.

This is why Paul's theology changes so radically and so quickly. It's also why he never treats devotion to Jesus as idolatry. For Paul, honoring Jesus is honoring YHWH.

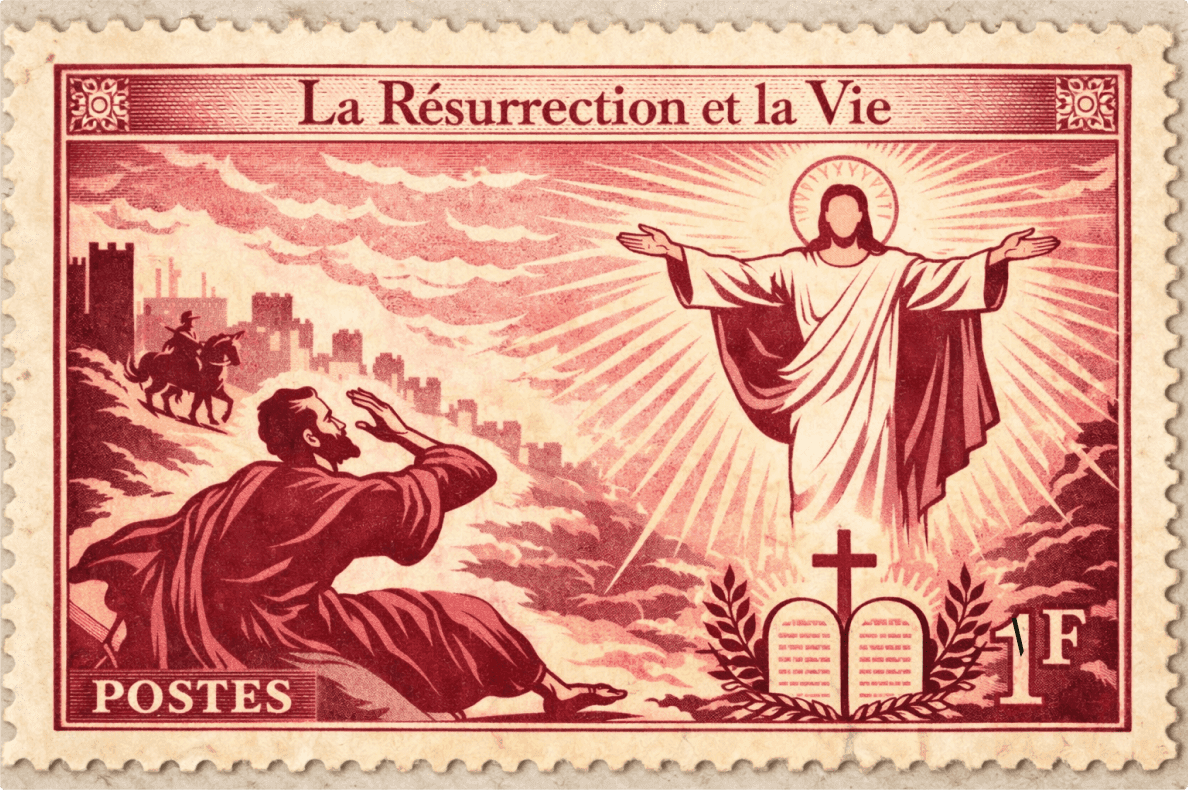

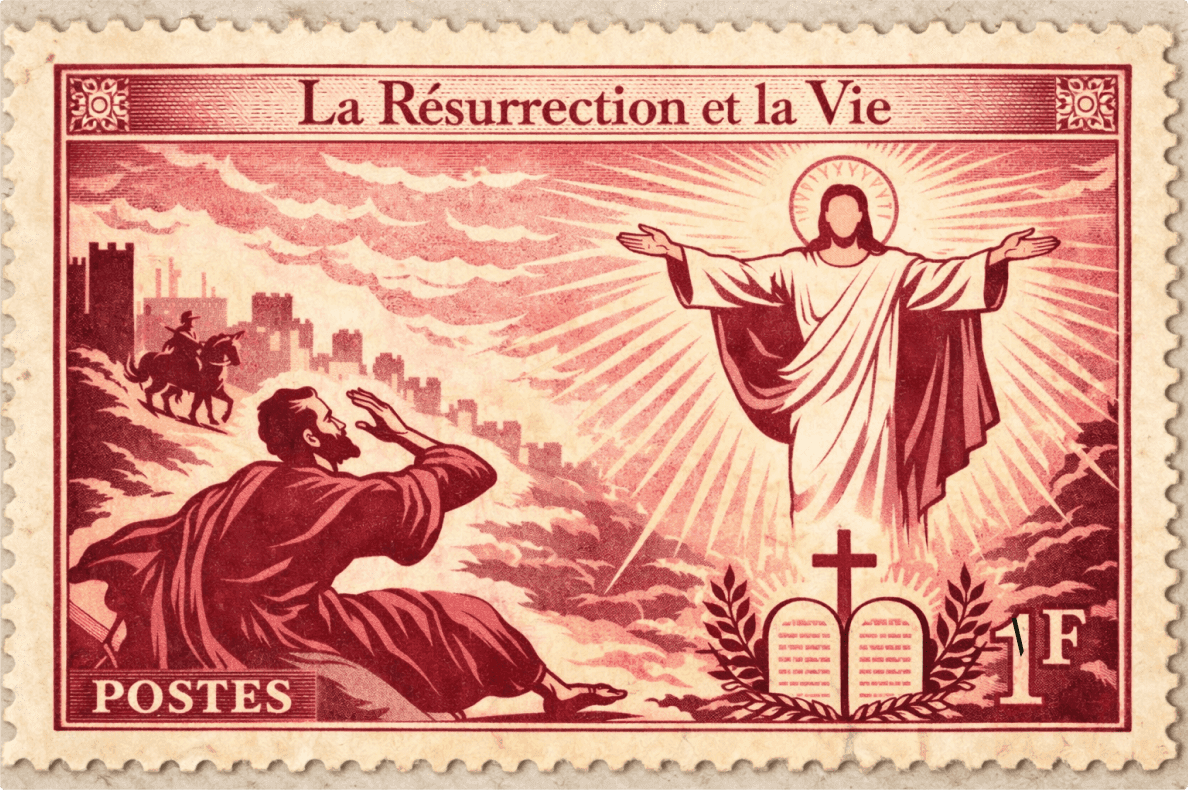

And we should remember one more crucial detail. Paul later describes this encounter as seeing "the risen Lord" (1 Corinthians 15:8). This wasn't just any theophany. It was an encounter with the resurrected Messiah, which meant, in Jewish eschatology, that the age to come had broken into the present. The one Paul saw wasn't merely YHWH revealed in human form. He was YHWH who had entered death itself and emerged victorious.

The resurrection changes everything. A dead Messiah was a failed Messiah. A resurrected Messiah was something no first-century Jew had categories for. And when that resurrected figure identified himself as the one to whom Israel's Scriptures pointed, as the bearer of the Divine Name, as the presence before whom every knee would bow, Paul had no choice but to rethink everything he thought he knew about God, Israel, and the world.

That rethinking began on the Damascus Road. It continued through every letter Paul wrote. And it rests on the conviction that when he said "Lord, who are you?" he was addressing the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who had now made himself known in Jesus of Nazareth.

The Invitation That Remains

We can't read Paul's mind, of course. We can't reconstruct his private thoughts with absolute certainty. But we can reconstruct his world. And in that world, all the evidence points in the same direction.

When Paul said, "Lord, who are you?" he believed he was addressing YHWH. The revelation of the Damascus Road was not that God had been replaced, but that God had made himself known in Jesus of Nazareth. That single moment reshaped everything Paul believed about God, Scripture, and the meaning of Israel's faith.

So perhaps the next time we read those words, "Who are you, Lord?" we might pause before softening them into polite conversation. The question wasn't casual. The answer wasn't comfortable. And the implications, for Paul and for anyone who takes his witness seriously, remain as unsettling and unavoidable as they were on that dusty road two thousand years ago.

The voice still speaks. The light still blazes. And the question Paul asked, whether we realize it or not, is the same question the story keeps asking us.

Who do you say that I am?

When Paul Said "Lord," Did He Mean YHWH?

Here's an odd thing. Ask most Christians what happened on the Damascus Road, and they'll tell you Paul met Jesus (YHWShA). Ask them what Paul's first words were, and they'll say something like, "Who are you, sir?" The word "Lord" gets heard as a polite form of address, the kind of thing you might say to a stranger who's just startled you on the street.

But that reading, however natural it feels in English, tells us more about our cultural instincts than about Paul's world. And if we're going to understand what actually happened in that moment, we need to step back into the mental furniture of a first-century Pharisee, trained in Scripture, steeped in synagogue life, praying the Shema every morning and evening.

When we do that, a rather different picture emerges.

The Language Paul Breathed

Paul didn't invent his religious vocabulary on the Damascus Road. He inherited it. As a Pharisee, he had been shaped by Israel's Scriptures in both their Hebrew form and their Greek translation, the Septuagint. This matters more than we might first imagine.

In Greek-speaking Jewish communities, the Divine Name (YHWH) was not pronounced. When the text read יהוה, the reader spoke aloud kyrios, "Lord." Over time, this wasn't just a reading convention. It became the standard way Greek-speaking Jews referred to and addressed the God (YHWH) of Israel. Not a vague honorific. A reverent substitute for the Name itself.

There was a seminary student once who asked whether Paul might have meant "sir" when he said kyrios on the road to Damascus. The professor responded with a simple challenge: "Show me one instance in Jewish literature where someone addresses an unidentified heavenly voice as 'sir.'" The student couldn't. None of the class could. That's the problem.

When Paul used kyrios in the presence of what appeared to be a divine manifestation, he wasn't reaching for a neutral term. He was using the language he had always used for Israel's God.

The Pattern of Encounter

The story itself follows a script that runs throughout Israel's Scriptures. A divine presence appears, often accompanied by overwhelming light or fire. A human being is struck with fear or physically incapacitated. The human addresses the presence as the God of Israel. Only then does fuller revelation come.

Moses at the burning bush. Isaiah in the temple. Ezekiel by the river. In the Hebrew text, these figures likely addressed YHWH directly, speaking the Name itself. But something changed during and after the Babylonian exile. Whether out of heightened reverence, protective instinct, or deepening interpretation of the third commandment, Jewish communities began to avoid pronouncing the Divine Name. Instead, they substituted Adonai when reading aloud.

This wasn't a casual shift. It reflected Israel's post-exilic wrestling with holiness, identity, and how to guard what was most sacred after everything had been lost and then partially restored.

By the first century, this practice had become standard, especially in Greek-speaking Jewish communities. When scribes translated the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek, the Septuagint, they rendered YHWH as kyrios, "Lord." And when Paul read Isaiah's vision, he read Isaiah crying out, "Kyrios of hosts!" When he read Moses at the bush, he read Moses asking, "Who shall I say sent me, Kyrios?"

So when Paul encountered a blinding light and a voice from heaven, his scriptural reflexes (trained on the Greek text and centuries of post-exilic reverence) would have reached for kyrios as the natural way to address the God of Israel in a theophany. Not because Moses said it that way, but because Paul's Bible and his liturgical practice taught him to say it that way.

That's the point. The pattern of divine encounter was ancient. But Paul's linguistic response to it was shaped by his Septuagint-saturated, post-exilic Jewish world.

Why "Sir" Simply Won't Work

Of course, one can argue for the polite reading. Many thoughtful people do. But the argument collapses under its own weight when you press on it.

First, the circumstances. This isn't someone tapping Paul on the shoulder at the marketplace. He's surrounded by heavenly light and struck blind. Second, Jewish usage. Greek-speaking Jews didn't casually sprinkle kyrios into conversations with mysterious voices from above. Third, the biblical pattern. Every comparable narrative of divine encounter involves an address to the God of Israel before the revelation of identity, not after.

What you cannot do, not if you want to remain consistent with the evidence, is read Paul's response as if he were speaking to a stranger on the street. The cultural and literary context simply doesn't support it.

What Paul Did Next

Here's where the argument becomes even stronger. If Paul later believed he had mistakenly addressed Jesus as YHWH, we would expect some clarification, wouldn't we? Some careful explanation in his letters. "I thought at first it was God himself, but of course I came to understand it was the Messiah, acting on God's behalf."

We get nothing of the kind.

Instead, Paul's theology moves decisively in the opposite direction. He takes passages about YHWH and applies them directly to Jesus. Not carefully. Not apologetically. Directly.

Joel promises that "everyone who calls on the name of YHWH will be saved." Paul applies that to calling on Jesus. Isaiah declares that every knee will bow to YHWH alone. Paul applies that to Jesus. These aren't casual proof texts. They're some of Israel's most fiercely monotheistic declarations. Paul knew Isaiah insisted, "I am YHWH, and there is no other." And yet he places Jesus right there, within that exclusive identity.

This only makes sense if Paul believed that the one he encountered on the Damascus Road was not a lesser agent of God, but God himself revealed in and as Jesus.

Rewriting the Shema

The most revealing move comes in 1 Corinthians 8:6. There, Paul does something no Torah-faithful Jew would dare attempt without direct revelation. He reformulates Israel's central confession.

"There is one God, the Father," he writes, "and one Lord, Jesus Messiah."

If we were to render Paul's theological logic back into Hebrew, using the Divine Name as his Greek "Lord" implies, it would read something like this:

אלהים אחד האב ויהוה אחד יהושע המשיח

Alohim echad ha-Av, ve-YHWH echad Yahusha ha-Mashiach

Or in English, preserving the Divine Name:

"One God, the Father, and one YHWH, Jesus (Yahusha) the Messiah."

Read that again slowly. Paul isn't adding a second god alongside YHWH. He's placing Jesus inside the identity of YHWH himself. This isn't the introduction of a second god. It's the deliberate placement of Jesus inside the confession of Israel's one God.

Think of it this way. John tells us that "the Word became flesh and dwelt among us" (John 1:14). That word dwelt is eskēnōsen in Greek, which literally means "tabernacled." John is saying that in Jesus, YHWH did what he promised in the wilderness and in the temple: he came to dwell with his people. Not through a tent or a building this time, but in human flesh.

Paul says something similar when he writes of "God manifest in the flesh" (1 Timothy 3:16). This is the mystery the early Christians confessed. The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the one who led Israel through the wilderness, the one whose glory filled the temple, had now tabernacled among his people in a new and final way.

The word "Lord" here is doing exactly what it did in the synagogue, standing in for the Divine Name. Paul is saying, in effect, that the identity of YHWH now includes both the Father and Jesus the Messiah.

I grew up in a Catholic household where the Trinity was a settled fact, something you learned from the catechism and didn't question. Later, in Oneness Pentecostal circles, I heard passionate sermons about Jesus being Lord, about the Name, about the fullness of the Godhead dwelling bodily. But it took reading Paul in his own world to realize what a staggering claim this was. Paul wasn't softening Jewish monotheism. He was reshaping it from the inside out, and he was doing so because of what happened on that road.

The Name Above Every Name

And Paul's claim goes even further. When he writes to the Philippians that God gave Jesus "the name above every name," so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow (Philippians 2:9-11), he isn't speaking of a new title or honorary designation. He's claiming Jesus bears the Name itself.

This is where the pieces lock together. Isaiah declared that to YHWH alone every knee will bow and every tongue confess. Paul takes that uncompromising monotheistic statement and applies it to Jesus without qualification. The name above every name isn't "Lord" as a generic honorific. It's the Name that "Lord" stood in for, the Tetragrammaton itself, YHWH, the name Jews spoke as kyrios out of reverence but understood as the unique identity of Israel's God.

Think of it this way. Israel's Scriptures spoke of YHWH's Name dwelling in the temple, going before the people in the wilderness, carrying divine authority and presence. The Name wasn't a label. It was a way of talking about God's active presence in the world. When Paul says Jesus bears the name above every name, he's not adding Jesus to a pantheon. He's identifying Jesus as the embodied presence of YHWH himself.

This is the logic of the Damascus Road worked out in Paul's theology. The voice that identified itself as Jesus was the same voice Paul addressed as kyrios, the same presence Isaiah saw high and lifted up, the same God before whom every knee must bow.

The Logic of the Moment

Put it all together and the logic becomes inescapable. Paul encountered a divine presence. He addressed that presence as kyrios, meaning the God of Israel. The voice revealed itself as Jesus. Paul did not conclude that he had been mistaken about encountering God. He concluded that Jesus belonged within the identity of Israel's God.

This is why Paul's theology changes so radically and so quickly. It's also why he never treats devotion to Jesus as idolatry. For Paul, honoring Jesus is honoring YHWH.

And we should remember one more crucial detail. Paul later describes this encounter as seeing "the risen Lord" (1 Corinthians 15:8). This wasn't just any theophany. It was an encounter with the resurrected Messiah, which meant, in Jewish eschatology, that the age to come had broken into the present. The one Paul saw wasn't merely YHWH revealed in human form. He was YHWH who had entered death itself and emerged victorious.

The resurrection changes everything. A dead Messiah was a failed Messiah. A resurrected Messiah was something no first-century Jew had categories for. And when that resurrected figure identified himself as the one to whom Israel's Scriptures pointed, as the bearer of the Divine Name, as the presence before whom every knee would bow, Paul had no choice but to rethink everything he thought he knew about God, Israel, and the world.

That rethinking began on the Damascus Road. It continued through every letter Paul wrote. And it rests on the conviction that when he said "Lord, who are you?" he was addressing the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who had now made himself known in Jesus of Nazareth.

The Invitation That Remains

We can't read Paul's mind, of course. We can't reconstruct his private thoughts with absolute certainty. But we can reconstruct his world. And in that world, all the evidence points in the same direction.

When Paul said, "Lord, who are you?" he believed he was addressing YHWH. The revelation of the Damascus Road was not that God had been replaced, but that God had made himself known in Jesus of Nazareth. That single moment reshaped everything Paul believed about God, Scripture, and the meaning of Israel's faith.

So perhaps the next time we read those words, "Who are you, Lord?" we might pause before softening them into polite conversation. The question wasn't casual. The answer wasn't comfortable. And the implications, for Paul and for anyone who takes his witness seriously, remain as unsettling and unavoidable as they were on that dusty road two thousand years ago.

The voice still speaks. The light still blazes. And the question Paul asked, whether we realize it or not, is the same question the story keeps asking us.

Who do you say that I am?

EXPLORE MORE

Warrior Messiah

Jesus overturned tables as judgment, not a call to arms. When we make him a warrior, we commit the very idolatry he condemned.

LEARN MORE

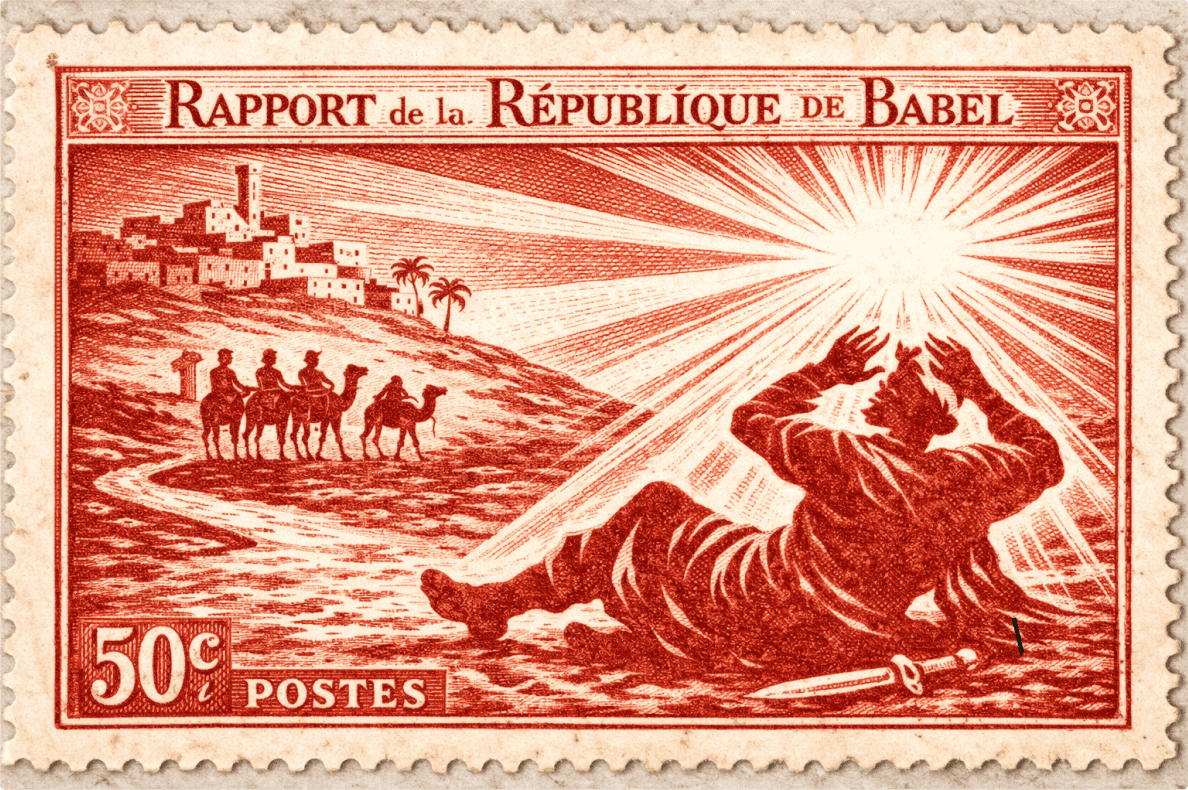

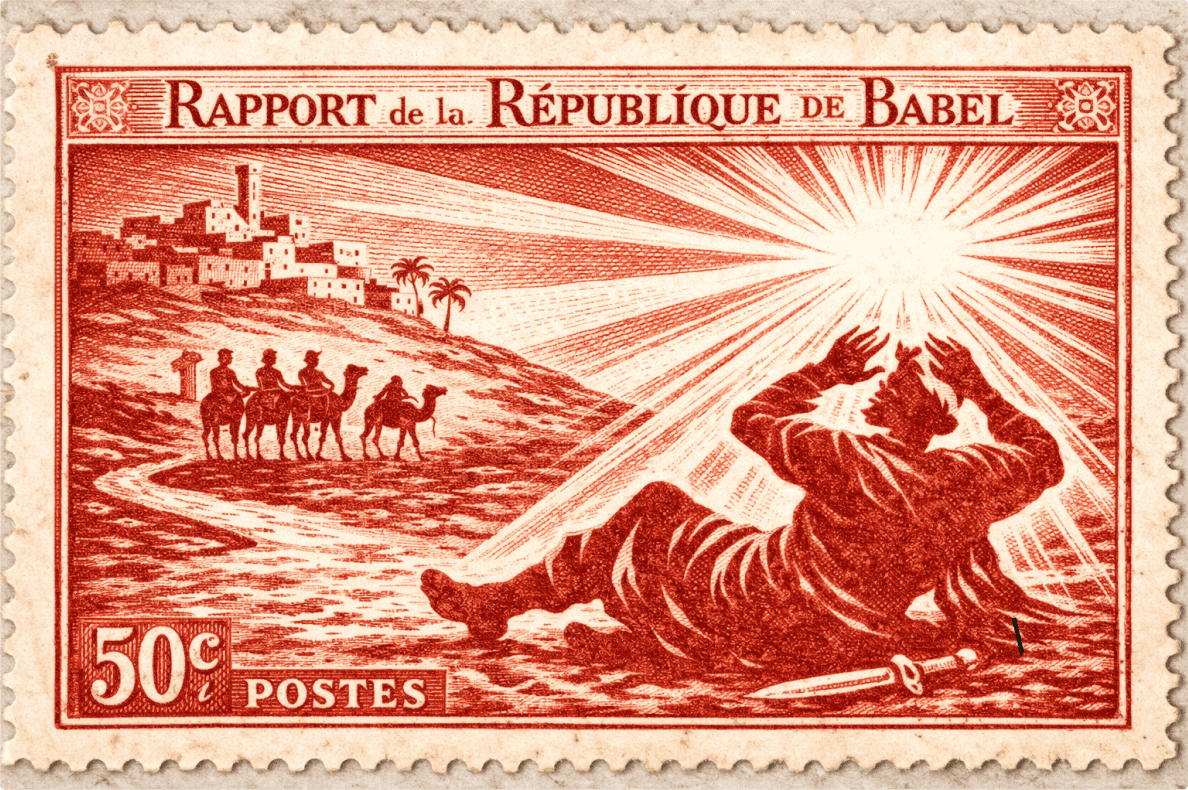

The Babel Problem

Religious diversity reveals humanity's fracture from one story, a catastrophic break only Christ can heal through resurrection.

LEARN MORE

Words Need Worlds

We condemn antisemitism while denying Noah existed. But "Semite" means Shem's descendants.

LEARN MORE

EXPLORE MORE

Warrior Messiah

Jesus overturned tables as judgment, not a call to arms. When we make him a warrior, we commit the very idolatry he condemned.

LEARN MORE

The Babel Problem

Religious diversity reveals humanity's fracture from one story, a catastrophic break only Christ can heal through resurrection.

LEARN MORE

Words Need Worlds

We condemn antisemitism while denying Noah existed. But "Semite" means Shem's descendants.

LEARN MORE

EXPLORE MORE

Warrior Messiah

Jesus overturned tables as judgment, not a call to arms. When we make him a warrior, we commit the very idolatry he condemned.

LEARN MORE

The Babel Problem

Religious diversity reveals humanity's fracture from one story, a catastrophic break only Christ can heal through resurrection.

LEARN MORE

Words Need Worlds

We condemn antisemitism while denying Noah existed. But "Semite" means Shem's descendants.

LEARN MORE