Death Isn't Natural

Death Isn't Natural

The Death We Cannot Accept: Why Resurrection Is the Only Coherent Hope

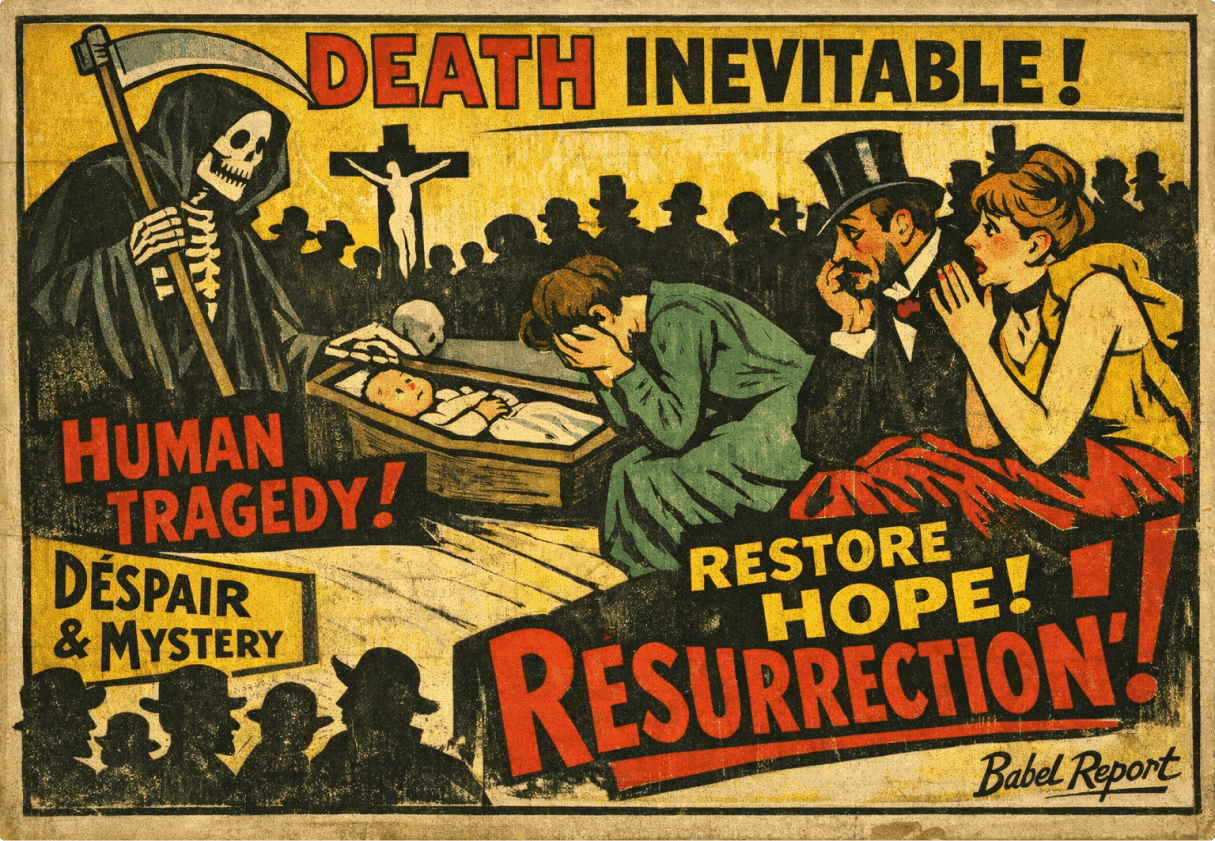

We live in a curious age. On one hand, our culture treats death as the ultimate taboo. We hide it in hospitals and nursing homes, sanitize it with euphemisms, and invest billions in medical technology to postpone what cannot finally be avoided. On the other hand, we are absolutely saturated with images of death. Our entertainment industry feeds endlessly on mortality. Crime dramas, zombie apocalypses, true crime podcasts. Fascinated and horrified in equal measure.

Here is what strikes me as most remarkable: even the most committed materialist, the person who insists we are nothing more than evolved primates destined for oblivion, still treats death as an intruder. No one eulogizes their pet hamster the way they eulogize grandmother. When a child dies, we do not shrug and say, "Well, natural selection." We rage. We grieve. We erect monuments and light candles and demand justice.

Death means something different when it is human. But if we are all just rearranged stardust, why should it?

This is not a rhetorical trick. It is a genuine puzzle. The vocabulary of our deepest moral intuitions keeps pointing us toward a story we claim not to believe. We speak of death as "untimely," as a "tragedy," as something that "shouldn't have happened." But according to what standard? If the naturalist worldview is correct, death is simply the cessation of biological function. Natural as digestion. Yet we cannot bring ourselves to treat it that way.

And that is the point. We are living off borrowed capital. The moral categories we use to process death, the outrage we feel at its presence, the dignity we insist on in our burial rites? All of this comes from a story. A very old story. One that begins in a garden and ends in a city. One that insists death was never part of the original design.

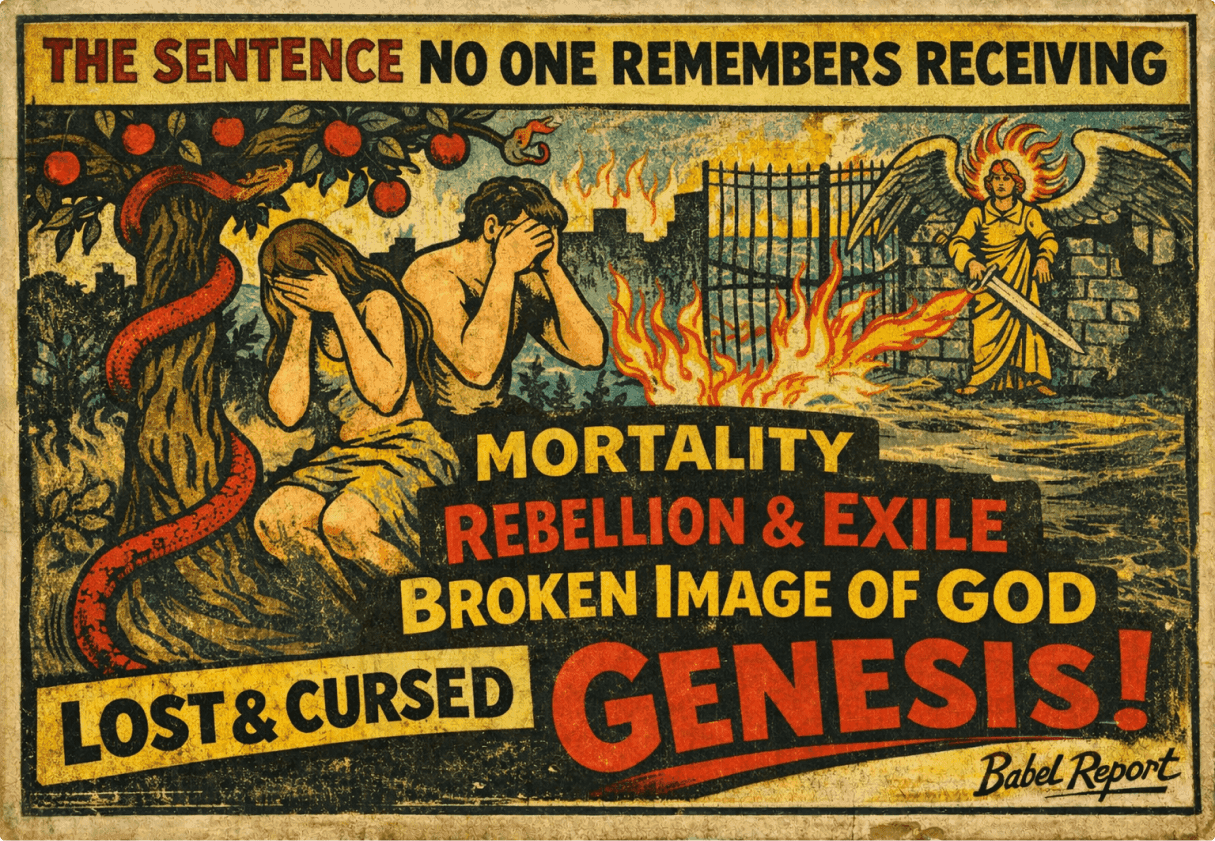

The Sentence No One Remembers Receiving

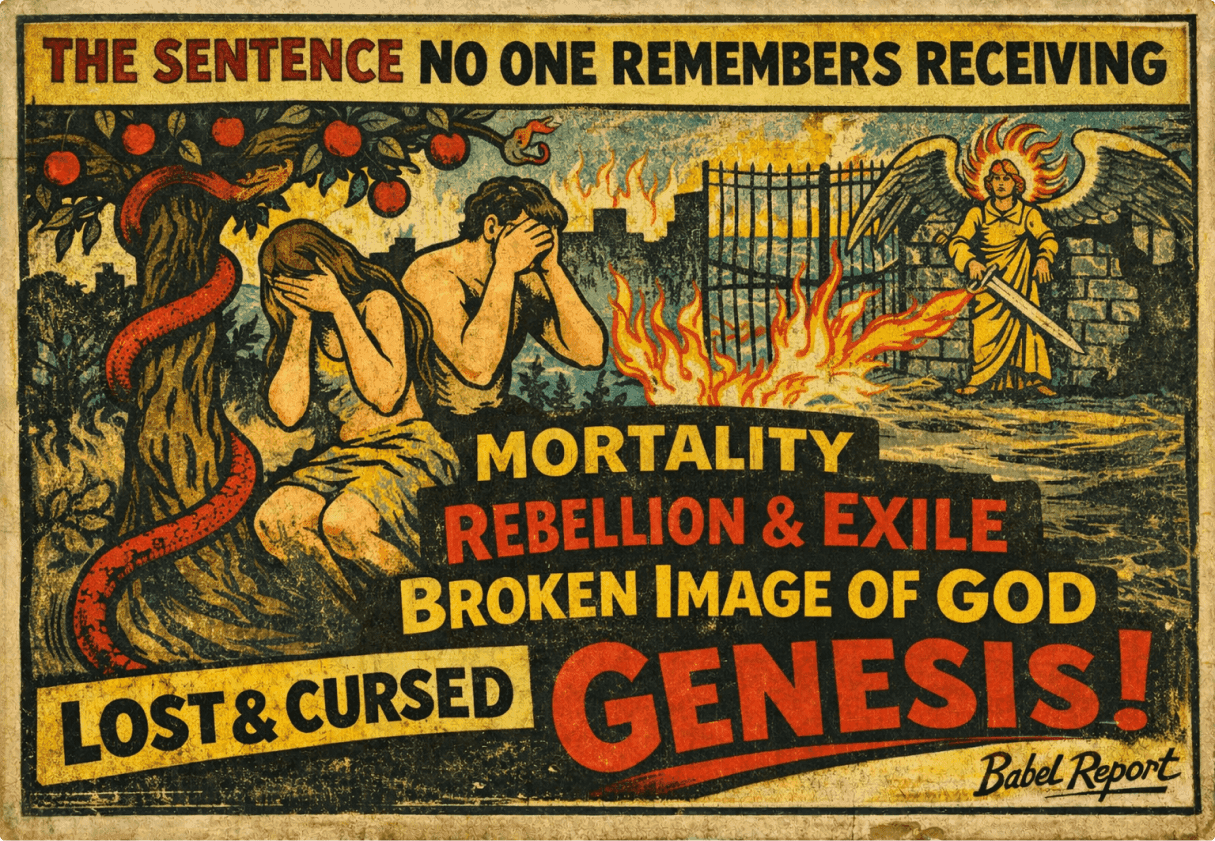

The opening chapters of Genesis present us with something far more sophisticated than a children's story about talking snakes. Here is a diagnosis of the human condition that has shaped Western consciousness so thoroughly that we forget where it came from. The narrative tells us that death entered the world through human rebellion, through what the biblical writers call "sin." Not a mistake. Not bad luck. Cosmic treason. The creatures tasked with representing the Creator's wise rule on earth chose instead to grasp at autonomy.

And the result? Exile from the place where heaven and earth overlapped. A sentence of mortality.

Now, one might dismiss this as ancient mythology. Many do, and for reasons they find compelling. But notice what you cannot do (not if you want to remain intellectually honest): continue to use the moral vocabulary this story provides while rejecting the story itself. You cannot call death "unnatural" or "tragic" without implicitly acknowledging that there was supposed to be a different state of affairs. Something was lost. Something broke.

I have spent years in different corners of the Christian world, and the one constant I have discovered is this: the biblical narrative provides a coherence that modern secularism simply cannot match. Not because I need it to be true. Because the alternatives keep collapsing under the weight of their own contradictions. The kingdom of God refuses to be claimed by any political tribe, left or right, and that refusal itself tells us something important about the nature of truth.

The Genesis account is not about an angry deity executing criminals. It is about the fracturing of a relationship that was meant to hold the cosmos together. God (YHWH) created humans in his image. Not as interesting biological specimens, but as his authorized representatives. The ancient term is imago Dei, the "image of God (Alohim)." This was a royal designation. Humans were commissioned to stand between heaven and earth, to reflect the Creator's character to the world and to offer the world's worship back to the Creator.

Kings and priests in one package.

When that relationship shattered, the commission was not simply revoked. It was damaged, distorted. And the symptom of this cosmic dislocation? Death. Not as punishment in the sense of retribution, but as the natural consequence of being severed from the source of life itself. Trees cut off from their roots do not thrive. They wither. This is what the biblical writers mean when they speak of being "in Adam." The entire human family inherited not guilt for Adam's specific act, but the condition his rebellion introduced. Mortality. Decay. Exile from the garden where life was sustained by communion with the Creator.

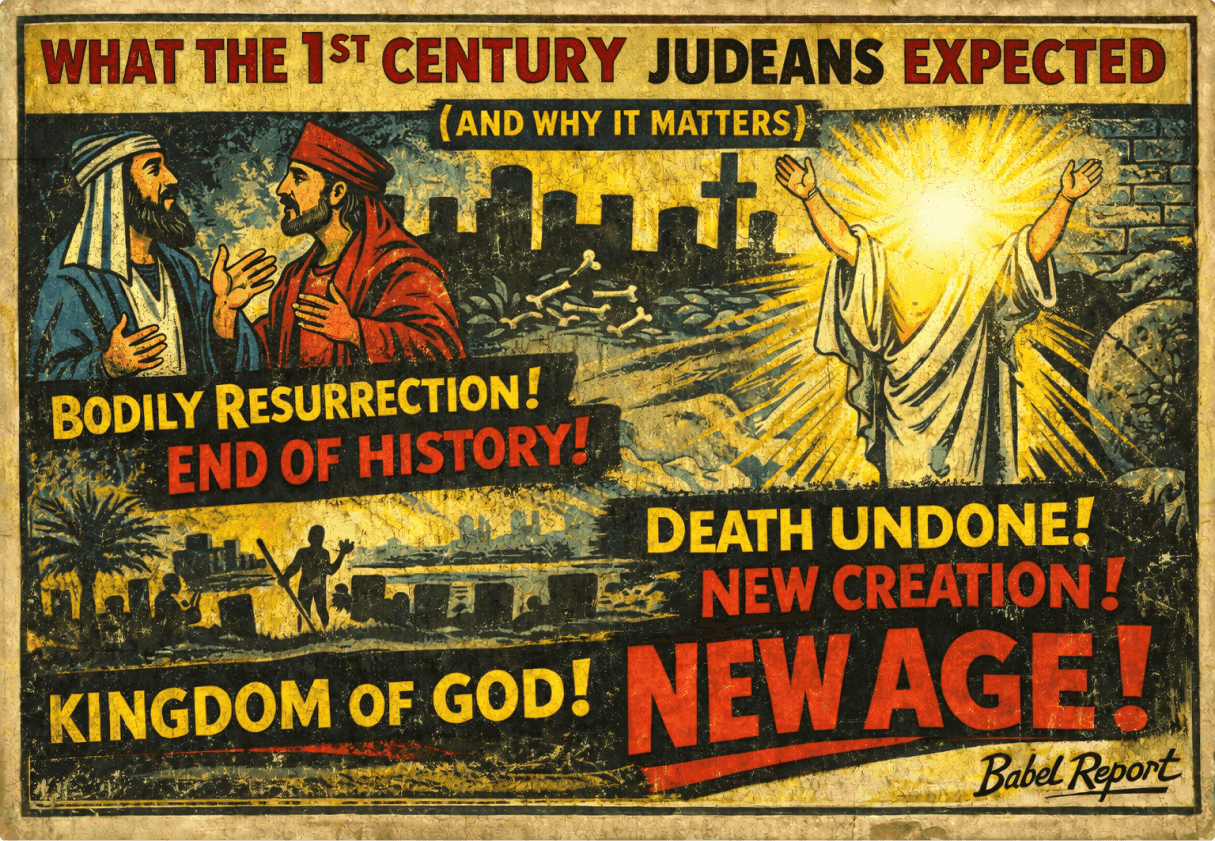

What the 1st Century Judeans Expected (And Why It Matters)

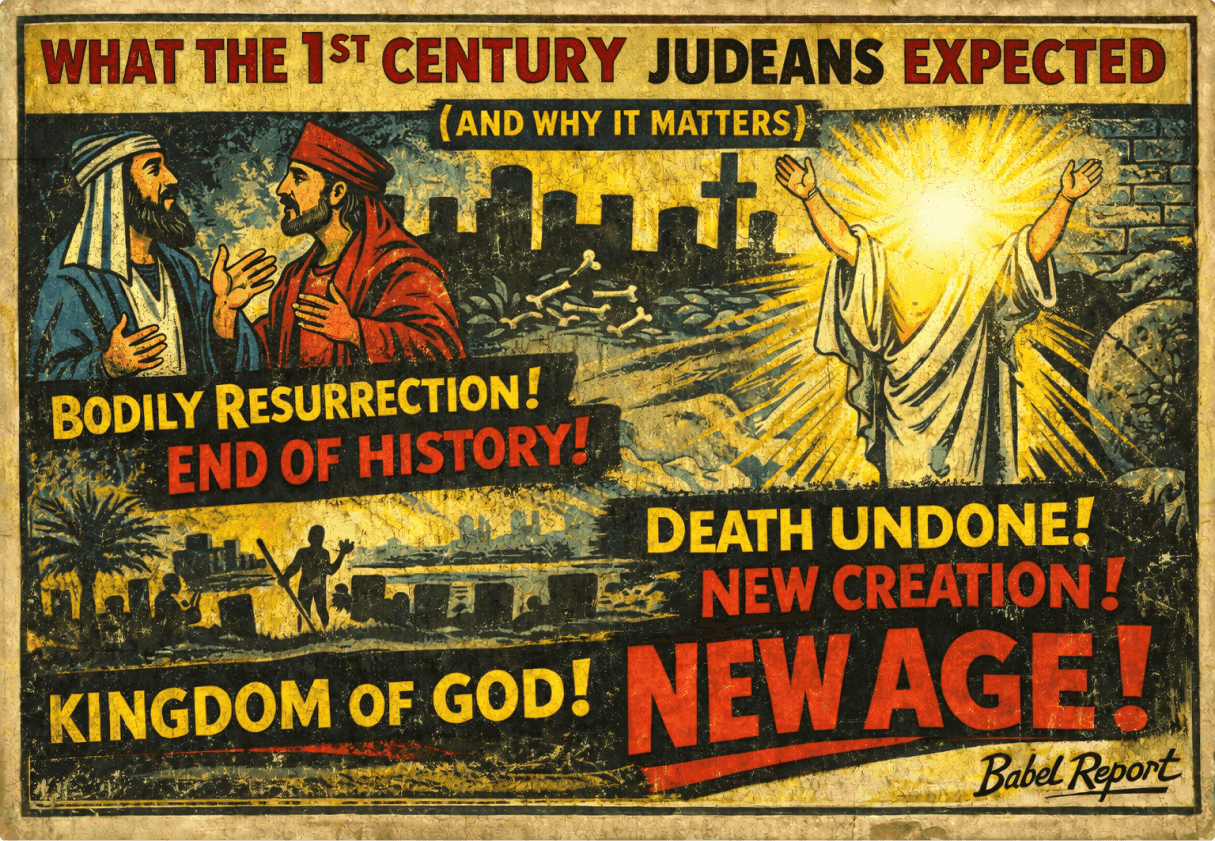

If you want to understand what the first Christians were claiming, you must first understand what Second Temple Judaism already believed about death and resurrection. This is where most modern readers go astray. We assume "resurrection" is just a poetic way of talking about the soul going to heaven.

The ancient Jews would have found this notion baffling.

By the time of Jesus (YHWShA), the Pharisees believed firmly in resurrection, while the Sadducees rejected it entirely. But notice what the Pharisees meant. They expected a bodily, physical resurrection of the dead at the end of history. Not the survival of an immortal soul, but the reconstitution of the whole person (body and all) when God finally stepped in to put the world right. This was not about individuals "going to heaven when they die." This was about the covenant God of Israel rescuing his people from exile, defeating the powers that held creation hostage, and inaugurating a new age where death itself would be undone.

The key detail is this: they expected it to happen all at once, for everyone, at the end of time. It would coincide with the arrival of God's kingdom in its fullness, when the whole created order would be renewed and the dead would be raised to inhabit the restored world.

So when the early Christians began announcing that Jesus had been raised from the dead, they were not simply reporting that his soul had gone to heaven. They were making a far more audacious claim. They were saying that the end-of-history event had already happened, in the middle of history, to one man. The age to come had broken into the present evil age.

The future had arrived early.

This is why the resurrection accounts in the Gospels are so insistent on the physical details. Jesus ate fish. He bore the scars from the crucifixion. He could be touched. Yet he also appeared in locked rooms and vanished from sight. The disciples were not describing a resuscitated corpse (like Lazarus, who would eventually die again). They were describing something unprecedented: a transformed physical body that belonged to the age to come but was already operative in the present age.

The Apostle Paul would later use the language of "firstfruits" to describe this. In the agricultural economy of the ancient world, the firstfruits were the initial portion of the harvest, offered to God as a sign that the full harvest was coming. Jesus's resurrection was the prototype, the advance demonstration of what God intended to do for all of creation. Not an isolated miracle. The invasion of the future into the present, the beginning of new creation.

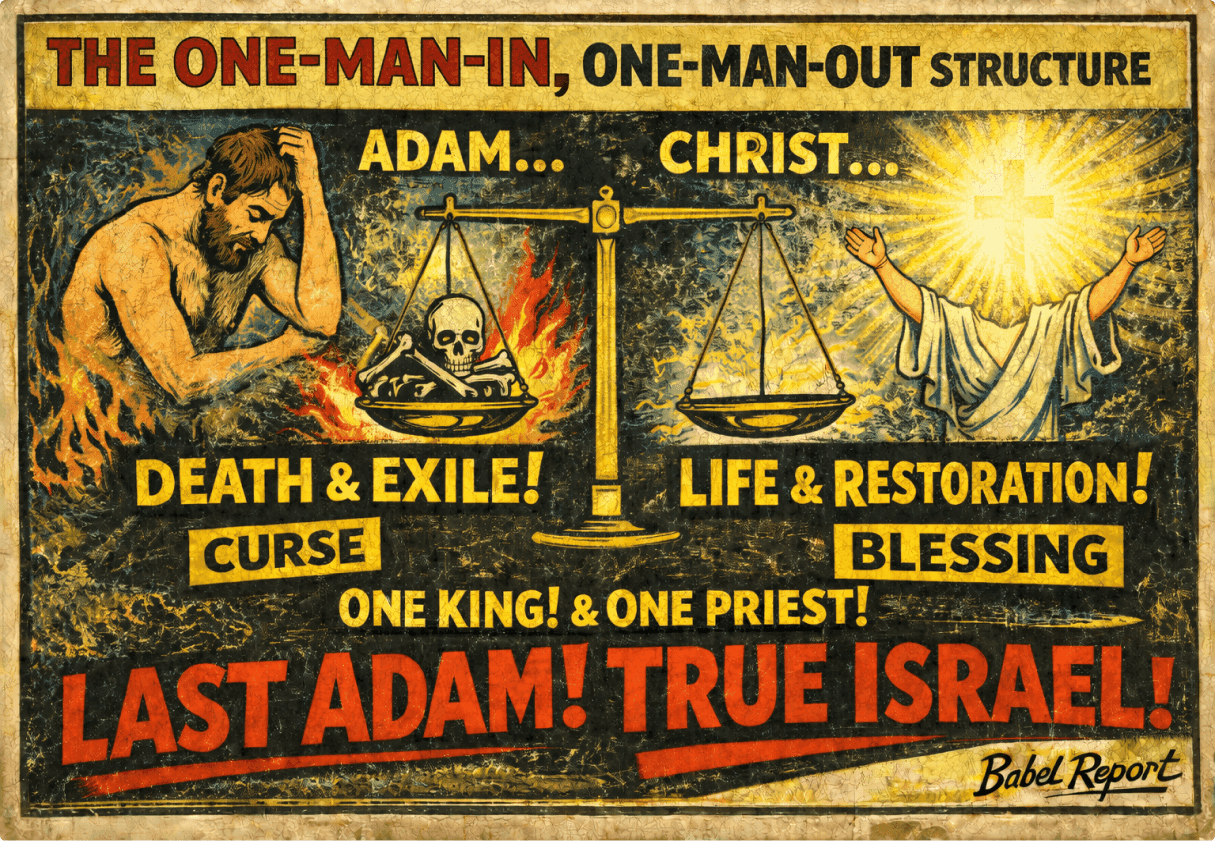

The One-Man-In, One-Man-Out Structure

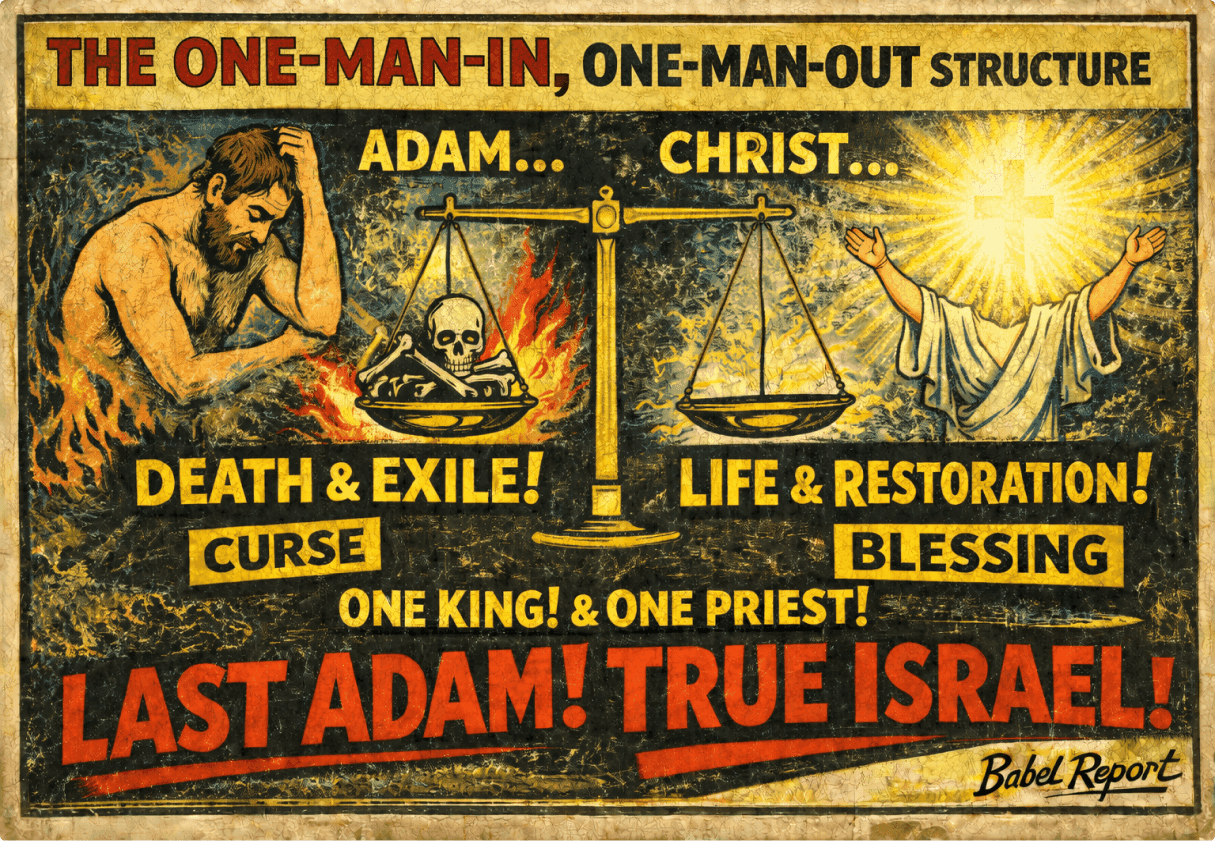

Here is where the story gains its full force. In Romans 5, Paul presents a shocking parallel: just as death entered the world through one man (Adam), so life enters the world through one man (Christ). The logic is cumulative. Adam, as the representative head of the human family, introduced the condition of mortality through his rebellion. Every descendant of Adam participates in that condition. We do not need to commit Adam's specific sin to experience death. We are born into a world where death reigns.

But here is the oddity. If the problem is universal, the solution must be equally universal. And that is precisely what Paul argues. Jesus, as the "last Adam," recapitulates the entire human story and reverses the trajectory. Where Adam chose autonomy and brought exile, Jesus chose obedience and brought restoration. Where Adam grasped at equality with God, Jesus (though he was in the form of God) emptied himself and became obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.

This is not a mere individual act of heroism. This is cosmic.

In the biblical worldview, representatives matter. When the king acts, the nation acts. When the priest offers sacrifice, the whole people are represented. Jesus, as both true Israel and true Adam, succeeded where both Adam and Israel failed. His obedience undid the curse. His resurrection demonstrated that death's power had been broken.

Now, you might say, "But people are still dying." Quite so. And here is where we must understand the biblical claim with more precision. The victory over death is not yet complete in its manifestation, but it is absolutely secure in its foundation. The resurrection of Jesus is the guarantee that what happened to him will happen to all who are united to him. The sentence of death still stands in one sense, but the appeal has been won.

The liberation is in process.

The Two-Stage Drama of New Creation

This brings us to the heart of the matter, and here we must tread carefully because Christian teaching has been muddied by centuries of Platonic influence. When most people think about Christian hope, they imagine something like this: you live a good life, you die, and if you have believed the right things, your soul goes to heaven and lives forever in bliss. The body? Well, that was just a temporary shell.

Good riddance.

This is not the biblical picture. Not even close.

The New Testament presents resurrection as a two-stage process, and understanding this distinction is essential. Let me put it as clearly as I can: the biblical hope is not that we escape the material world to live as disembodied souls in some ethereal heaven. The biblical hope is that heaven comes to earth, and that we (in resurrected, transformed physical bodies) take up our vocational calling as God's image-bearers in a world finally and fully renewed.

The first stage begins with what the early church called the "new birth." But notice how the biblical writers describe this entrance into new life. It is not merely a mental assent or an emotional experience. Peter's sermon on the day of Pentecost gives us the pattern: "Repent and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins, and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit" (Acts 2:38). Here are the three movements of entry into the resurrection life: repentance (a turning from the old age), baptism in the name of Jesus (a public identification with his death and resurrection), and the reception of the Spirit (the down payment of the age to come).

This was not a later theological development. This was how the earliest Christians understood entrance into the new creation from the very beginning. Baptism was not an optional add-on or a mere symbol. It was the threshold moment, the public enactment of dying with Christ and rising with him. When you went down into the water, you were buried with him. When you came up, you were raised to walk in newness of life. And in that same event, you received the Holy Spirit, described by Paul as the "firstfruits" or "down payment" of the age to come. In other words, you were given the life of the future now, in the present.

This is not mere metaphor. The earliest Christians genuinely believed they were participating in the resurrection life of Jesus by the power of the Spirit. They were not simply forgiven sinners waiting to die. They were new creations, already inhabited by the power of the age to come. This is why Paul can say in Romans 8 that those who have the Spirit are already "alive from the dead" in a spiritual sense, even though their mortal bodies are still subject to decay.

But notice the tension. This present life in the Spirit is real and powerful, but it is also incomplete. We groan, Paul says, waiting for the "redemption of our bodies." We are not waiting to be delivered from our bodies, but for our bodies to be delivered. And this is the second stage: the final, physical resurrection at the end of time.

When a Christian dies, they enter what theologians call the "intermediate state." The New Testament uses the language of "sleep" to describe this. Not because the person ceases to exist, but because death has been so fundamentally redefined by Christ's victory that it is no longer the ultimate horror. It is a temporary absence from the body, a state in which the believer is "away from the body and at home with the Lord," as Paul puts it in 2 Corinthians 5. This is a good thing, far better than the suffering and decay of this present age.

But it is not the final goal.

The final goal is the resurrection of the body at the end of history. This is when the scattered people of God are reconstituted as whole persons (body, soul, spirit, all of it) transformed into the likeness of Christ's glorified body. This is what Paul calls the "spiritual body" in 1 Corinthians 15, and the term is crucial. He does not mean a body made of spirit, some ghostly, immaterial thing. He means a physical, material body that is now animated and sustained by the Spirit of God rather than by mere biological processes. It is a body that is incorruptible, imperishable, glorious.

A seed that has been planted and has now burst forth in full bloom.

This is the moment when humans are finally and fully restored to their original vocation. The royal priesthood is re-enthroned. The image-bearers take up their calling to represent God's wise, self-giving rule to the world and to offer the world's worship back to God. And here is the astonishing claim: this re-enthronement of humanity is the specific trigger for the liberation of the rest of creation.

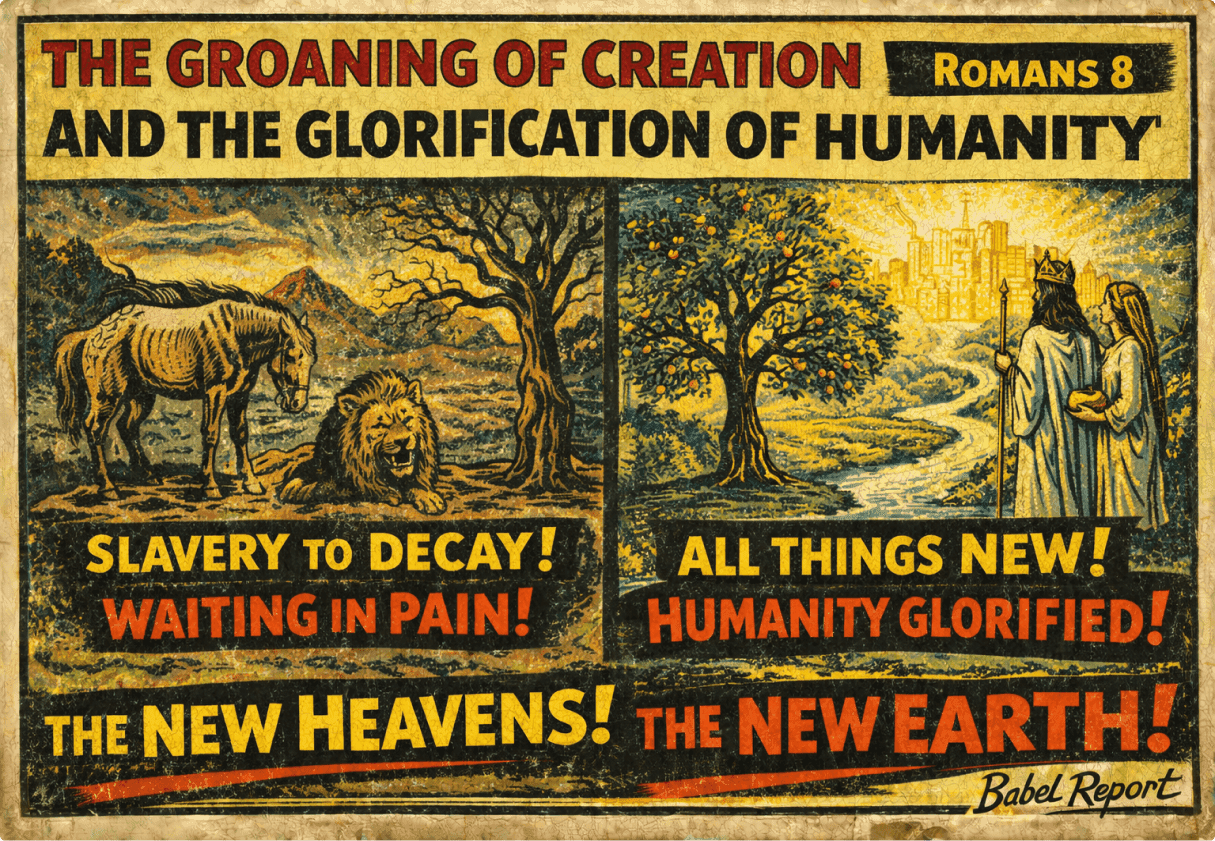

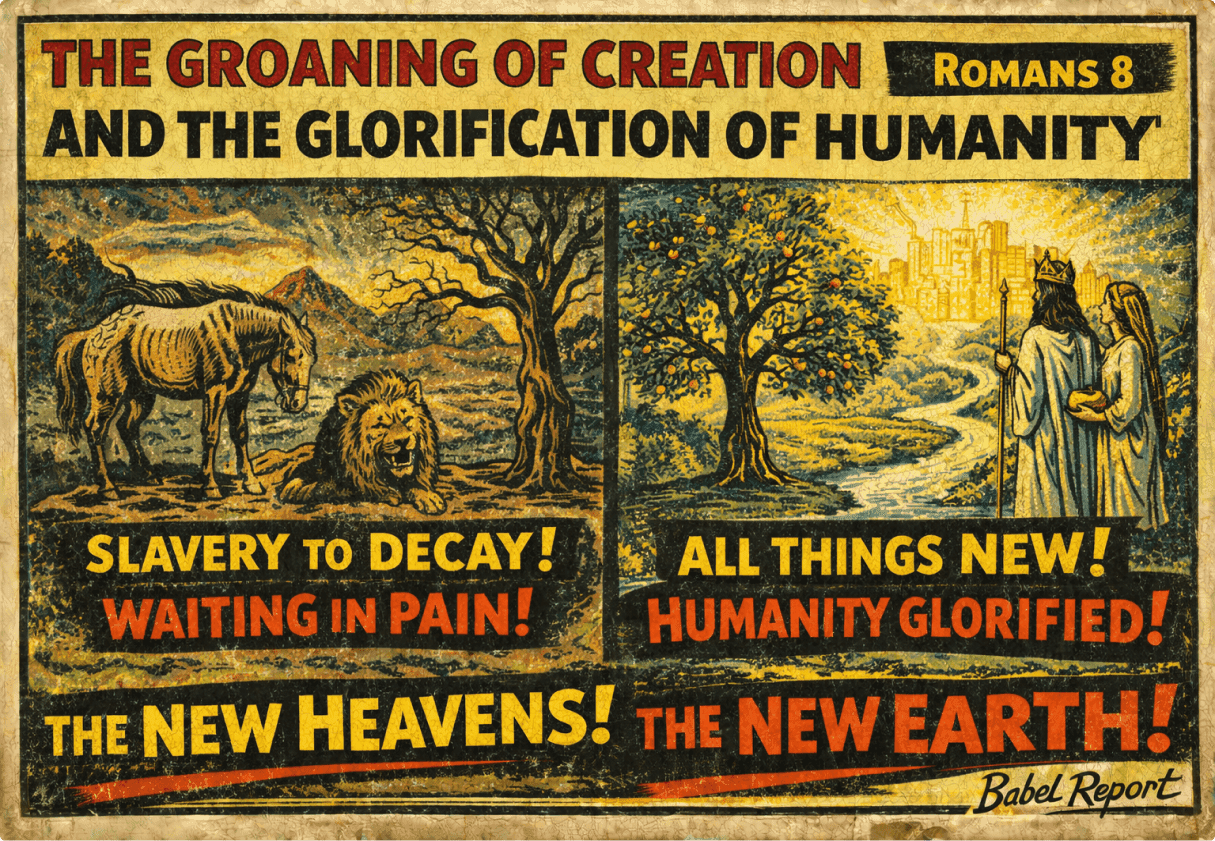

The Groaning of Creation and the Glorification of Humanity

Romans 8 contains one of the most stunning passages in all of Scripture. Paul tells us that the entire non-human creation is in a state of "slavery to decay" and is "groaning" as it waits for something. What is it waiting for? The "revealing of the sons of God." That is, the glorification of redeemed humanity in the final resurrection.

This is not incidental. The biblical worldview insists that the fate of the world is tied to the fate of humanity. When the image-bearers rebelled, the whole creation was subjected to futility. Not willingly, Paul says, but by the will of the one who subjected it (God allowed this as part of the consequences of human rebellion). And now, creation waits. It waits for the moment when the rightful rulers are restored to their thrones. When the kings and priests are finally functioning as they were meant to function, the kingdom (the earth itself) will be set right.

This is why the biblical vision of the future is not about escaping to some non-material heaven. The vision is of "new heavens and a new earth." Not brand-new in the sense of scrapping the old and starting from scratch, but renewed, transformed, purged of corruption. The language in Revelation 21 is remarkably concrete. Nations bringing their glory into the New Jerusalem. A river of life. The tree of life bearing fruit for the healing of the nations.

This is not metaphor for something else. This is the restoration of what was lost in Genesis 3, now glorified and made eternal.

And here is where the story becomes urgently relevant for how we live now. If the Christian hope is just about "going to heaven when we die," then this present world does not matter very much. We become Gnostics, waiting to escape the prison of matter. But if the Christian hope is about the renewal of all things, then what we do in this world matters enormously. The future has already broken into the present through Jesus's resurrection and through the gift of the Spirit. We are not just waiting.

We are participating.

The Already and the Not Yet

This is the strange, productive tension at the heart of Christian existence. The age to come has already begun in Jesus. The powers of the new creation are already at work through the Spirit. But the old age has not yet passed away. We live in the overlap, in what theologians call the "already and not yet."

Already, we have been raised with Christ. Already, we are seated with him in the heavenly places. Already, we are a new creation. But not yet have we received our glorified bodies. Not yet has death been finally and fully abolished. Not yet has the earth been renewed.

This is not a contradiction. This is the way God has chosen to work. The kingdom has been inaugurated, but it has not yet been consummated. And in the meantime, we live as witnesses to the future that is breaking in. We are, to use Paul's language, "Temple-people." Walking points where heaven and earth overlap. Through acts of healing, storytelling, justice, compassion, and beauty-making, we bring the "putting-right" project of God into the present world.

This is not triumphalism. We do not pretend the kingdom has fully arrived. We still live in a world marked by suffering, injustice, and death. But we also do not resign ourselves to cynicism or despair. We work, we pray, we hope, because we know the end of the story.

The resurrection of Jesus is the guarantee that God's project will not fail.

Why the Body Matters (And Why Platonism Fails)

Let me address a common confusion directly. Many Christians, influenced more by Greek philosophy than by Scripture, have come to believe that salvation is primarily about the soul escaping the body. The body is a prison, a temporary shell to be discarded. Heaven is a place where we float as disembodied spirits, perhaps playing harps on clouds.

This is Platonism, not Christianity. And it fails on multiple levels.

First, it dishonors the creation. The biblical story begins with God declaring the material world "very good." Matter is not evil. Embodiment is not a problem to be solved. The problem is sin, corruption, decay. Things that have infected the good creation but are not intrinsic to it.

Second, it makes nonsense of the incarnation. If the goal were to escape physicality, why would God become flesh? Why would the Word take on a body, live in it, die in it, and then rise in it? The incarnation is not a detour. It is central to the whole story. God affirms the goodness of materiality by entering into it fully.

Third, it undermines mission. If this world is just a sinking ship and heaven is the lifeboat, then why bother with culture, art, justice, or ecology? Just save souls and wait for the end. But if God intends to renew the earth, if our resurrection bodies will inhabit a transformed physical world, then what we do now has eternal significance. We are not killing time. We are planting seeds.

This is why Paul insists so strenuously in 1 Corinthians 15 that the resurrection is physical. He uses the metaphor of a seed. You plant a bare kernel, and what comes up is something far more glorious, but it is still a plant. There is continuity and transformation. The resurrection body is not a completely different thing. It is this body, purged of corruption, made imperishable, and animated by the Spirit.

Paul gives us more detail. He describes the current body as a "natural body" (or more literally, a "soul body"), meaning it is animated by the life force that all creatures share. But the resurrection body is a "spiritual body," meaning it is a physical body now powered and sustained by God's own Spirit. Think of it as an upgrade in operating system. The hardware remains recognizably the same (Jesus still bore his scars), but the software that runs it is fundamentally different.

Incorruptible. Glorious. Imperishable.

This distinction matters because it shows us that the biblical hope is not about moving from physical to spiritual, from material to immaterial. It is about moving from corruptible to incorruptible, from mortal to immortal, from enslaved to liberated. The resurrection body is more physical than our current bodies, not less. It is what the human body was always meant to be.

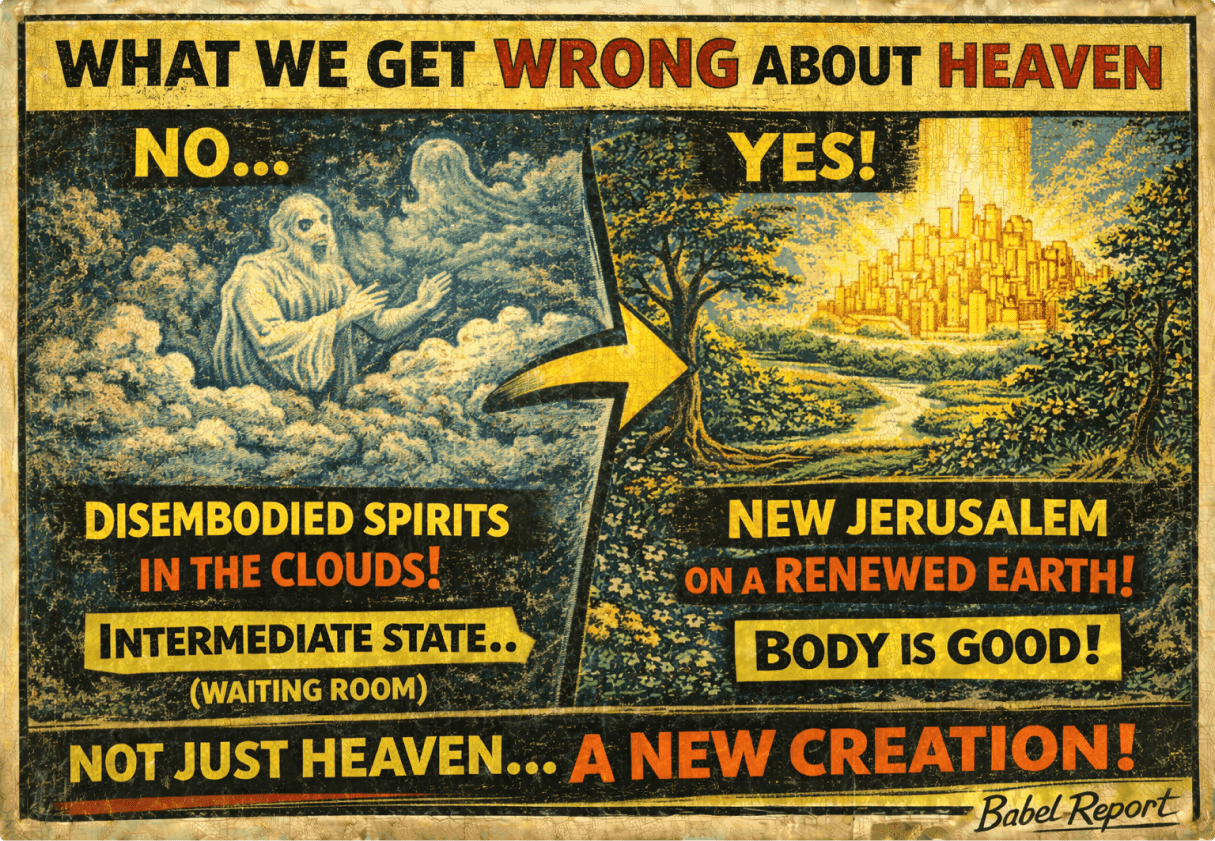

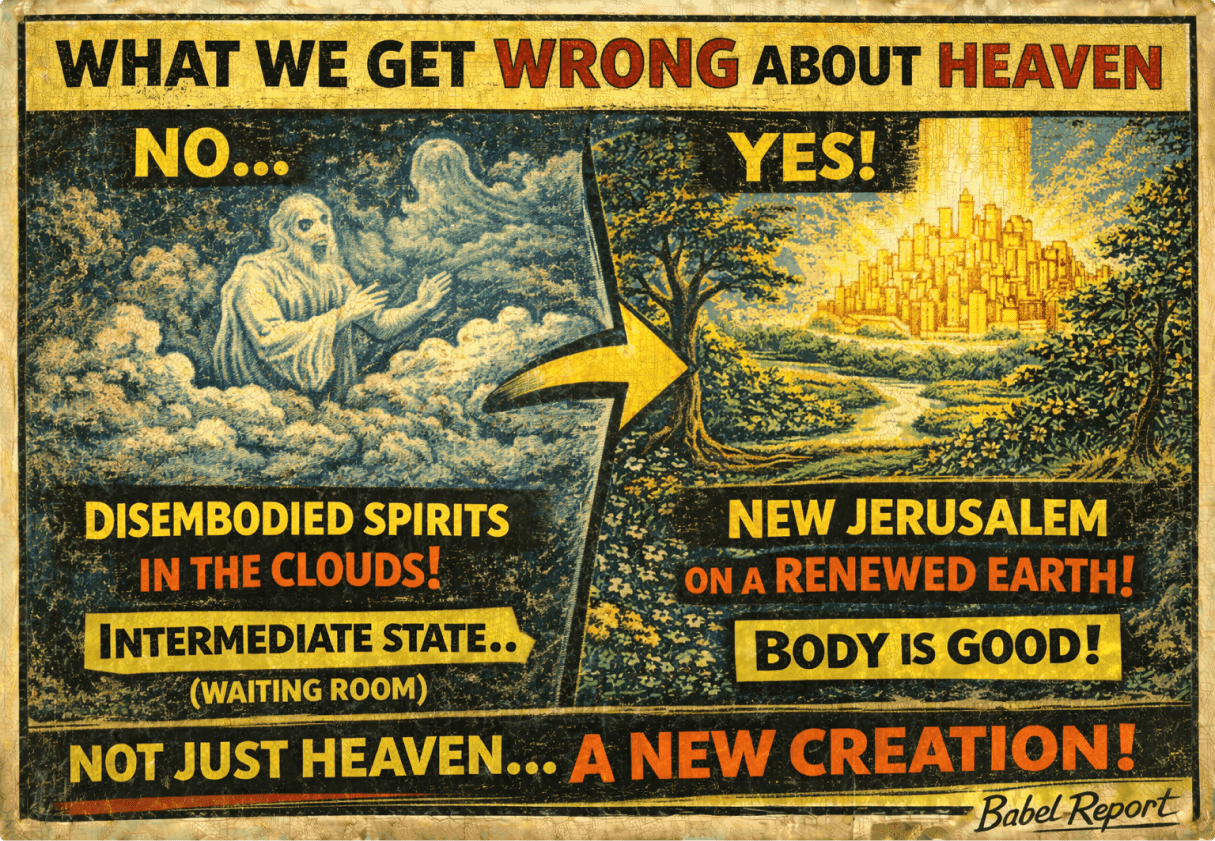

What We Get Wrong About Heaven

While we are on the subject, we need to address another persistent confusion. Ask the average person on the street what Christians believe about the afterlife, and they will probably say something about "going to heaven when you die." And to be fair, many Christians would say the same thing. But this is at best a half-truth, and at worst a profound distortion of the biblical vision.

The intermediate state (being "with the Lord" after death but before the resurrection) is real, and it is genuinely better than our current existence. Paul says as much. But it is not the ultimate destination. It is a waiting room, not the final home.

The ultimate destination is not "heaven" in the sense of some distant, ethereal realm far removed from earth. The ultimate destination is the renewed earth, the place where heaven and earth have finally and fully merged. This is what Revelation 21 describes: the New Jerusalem coming down from heaven to earth. God's dwelling place and humanity's dwelling place becoming one. The exile finally over. The garden restored and glorified into a city.

Why does this matter? Because if we think the goal is to "go to heaven," we will inevitably devalue the material world. Why care about justice on earth if the righteous are just waiting to escape? Why pursue beauty or truth or goodness in this world if the real action is somewhere else? But if the goal is the renewal of earth, then suddenly everything we do here carries weight. Our work, our relationships, our creativity, our justice-seeking are all part of the project.

This is not "social gospel" liberalism that abandons personal salvation for political activism. Nor is it fundamentalist escapism that abandons the world for pie-in-the-sky otherworldliness. It is the biblical vision that holds both together: God saves persons and God renews the world. The two cannot be separated.

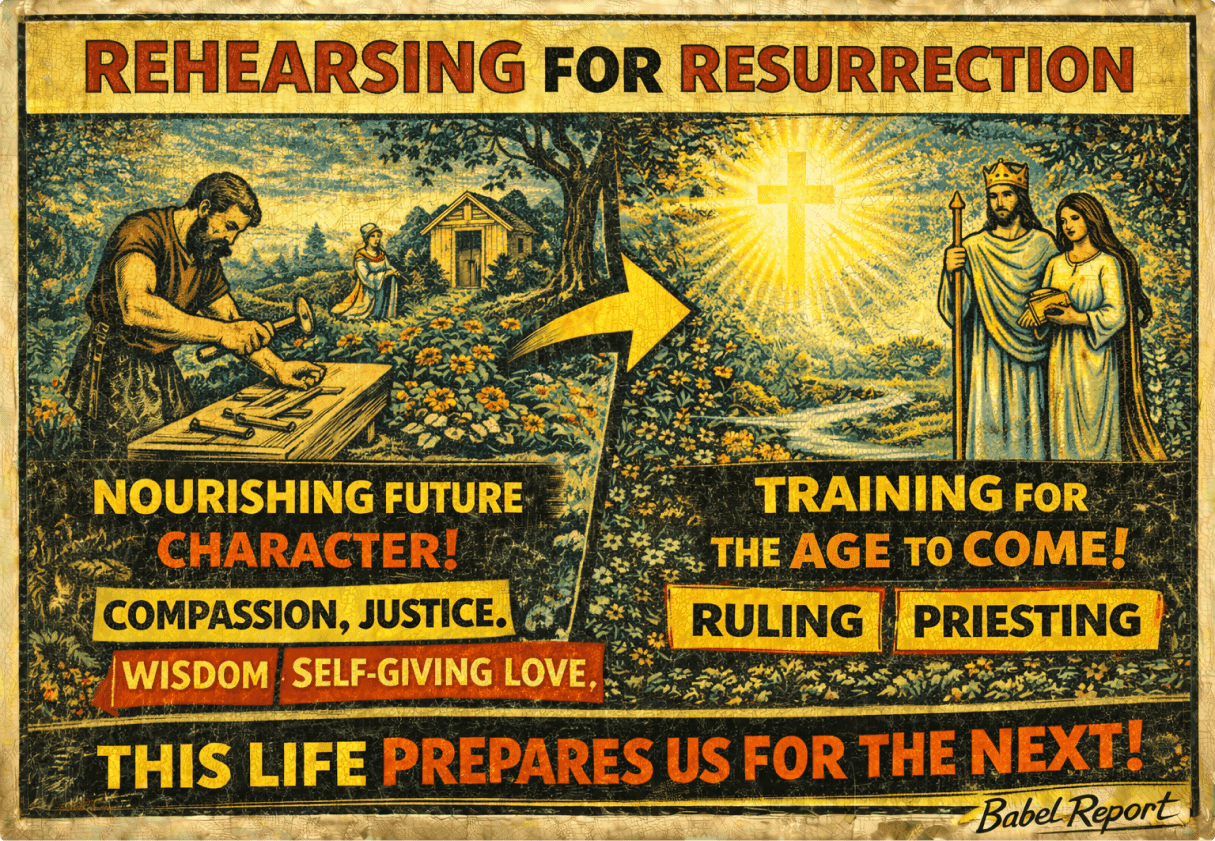

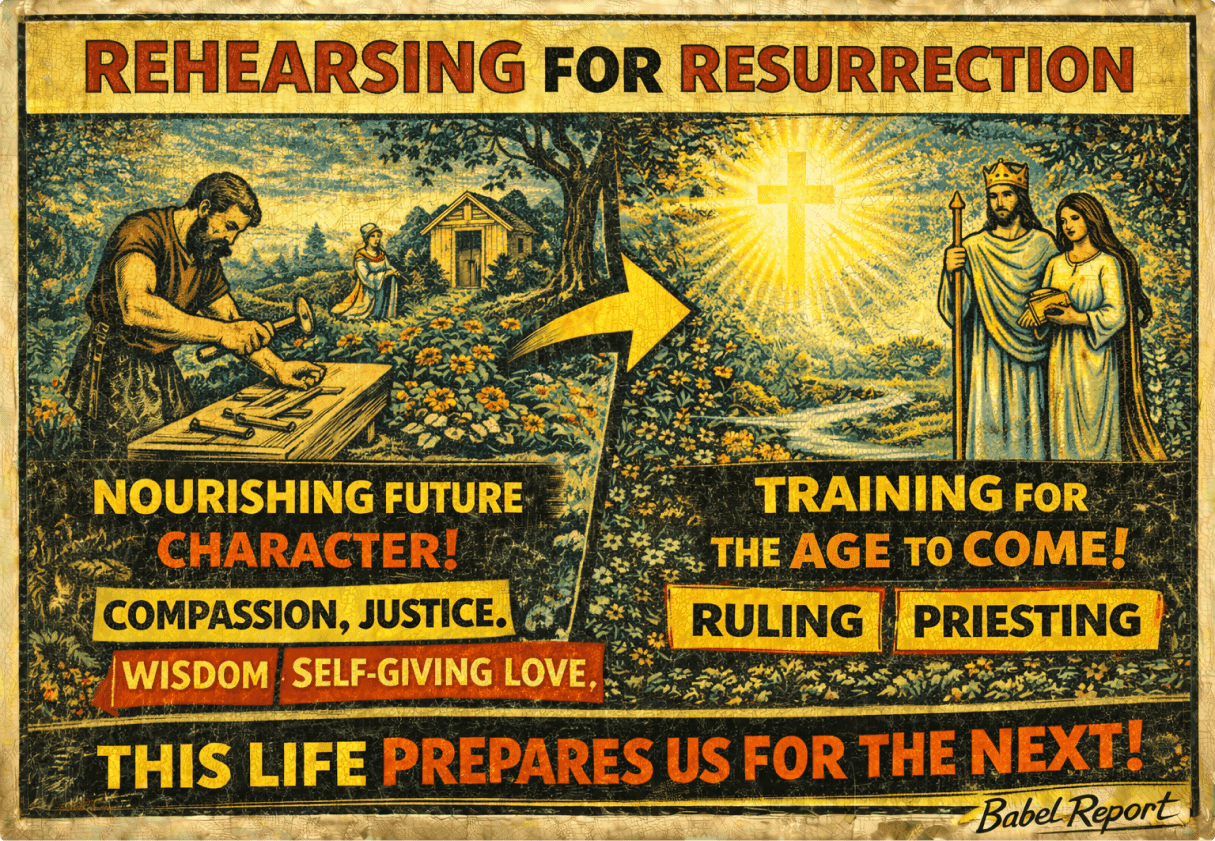

Rehearsing for Resurrection

So what does it look like to live in light of this hope? It means treating the present as training for the future. Paul tells the Corinthians that because we know the resurrection is real, our labor is not in vain. What we do in the body matters. The habits we form, the character we develop, the work we produce are all part of the material God will use in the new creation.

This is not works-righteousness. We are not earning our place in the kingdom through moral effort. We are justified by grace through faith, full stop. But justification is not the end of the story. It is the beginning. Having been declared members of God's family, we are now being formed into the kind of people who can wisely exercise the royal priesthood we are being restored to.

Think of it this way. If you knew you were going to be a surgeon, you would spend years in training. Not because the training earns you the position, but because the position requires certain skills and habits. In the same way, if we are going to be rulers and priests in the new creation, it makes sense that we would spend this life developing the virtues required for that vocation.

Compassion. Justice. Wisdom. Self-giving love. These are not arbitrary rules. They are the character traits of the age to come, and we practice them now as a form of anticipation. We are rehearsing for the performance that will never end.

This is why Christian ethics matter. Not because God is a cosmic policeman waiting to punish infractions, but because the way we live now is shaping us into the people we will be forever. The habits we form are not left behind at death. They are transformed and purified, yes, but they are also carried forward. The person you are becoming now is the person you will be in the resurrection.

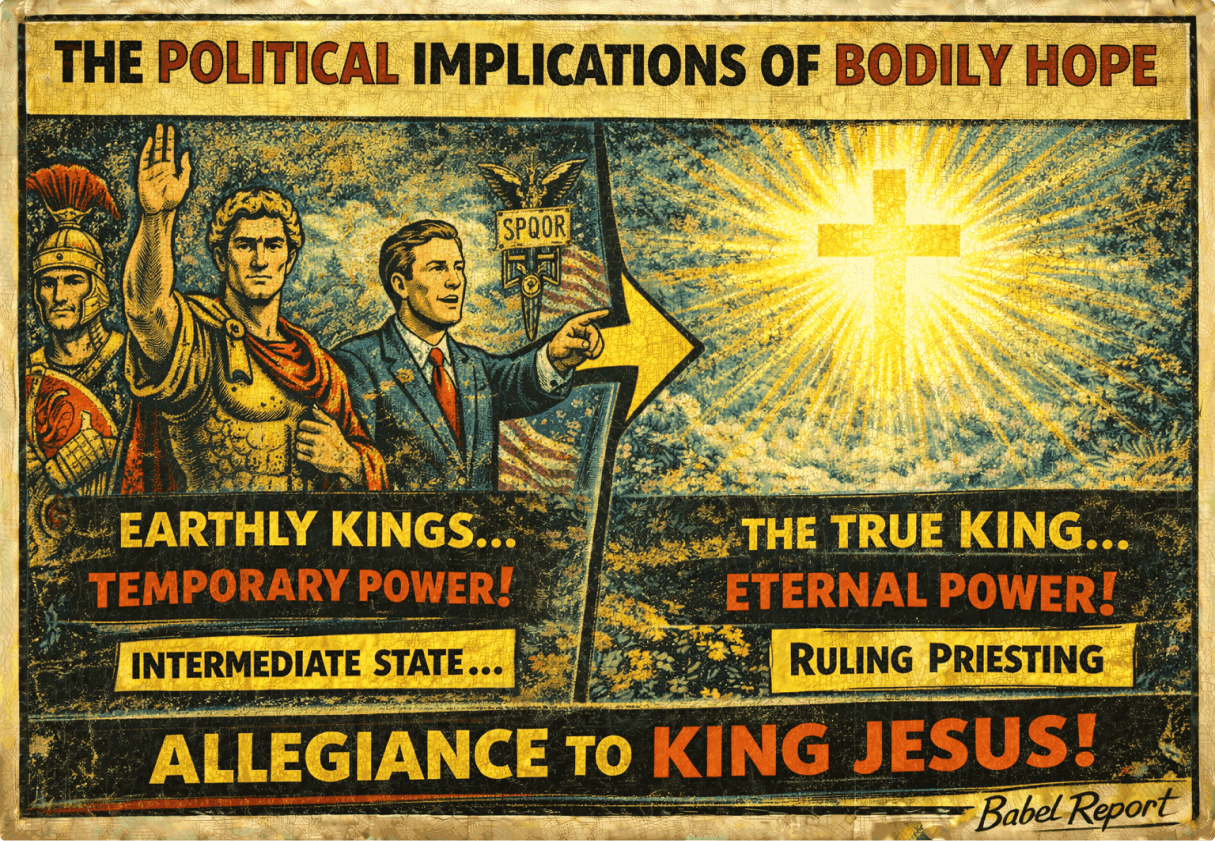

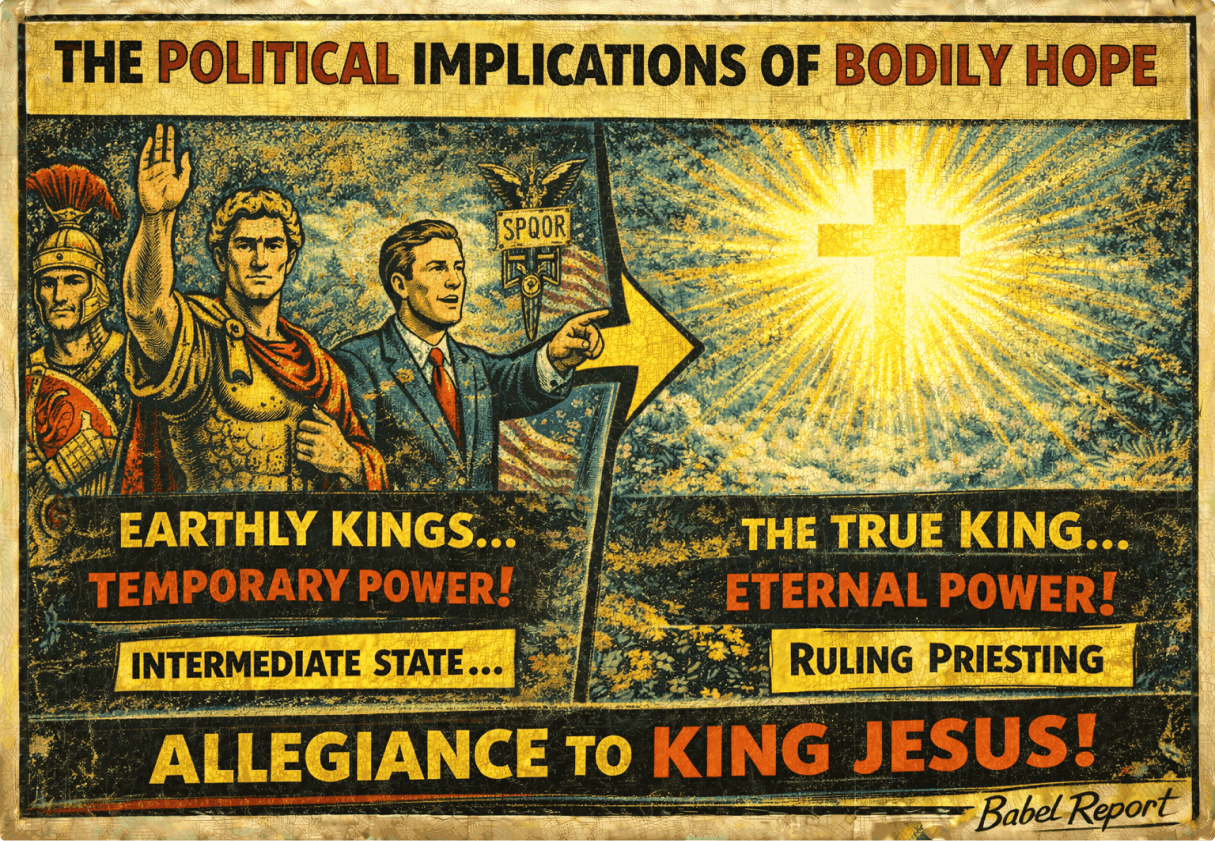

The Political Implications of Bodily Hope

I need to address something that will make some readers uncomfortable. The biblical vision of bodily resurrection has unavoidable political implications. Not in the sense of partisan politics (I have no allegiance to left or right, Democrat or Republican), but in the sense that it makes claims about how power works and who the true King is.

In the Roman world, the language early Christians used was directly subversive. Calling Jesus "Lord" (Kyrios) and "Savior" were the exact titles Caesar claimed. Announcing the "good news" (euangelion) of Jesus's kingdom was a rival proclamation to the Roman imperial gospel. When Paul wrote that every knee would bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, his readers would have immediately understood: not Caesar. Jesus.

This was not merely spiritual language. It was a public announcement that the world had changed, that a new King had been installed, and that ultimate allegiance now belonged elsewhere. The early Christians were not trying to overthrow Rome through violent revolution, but they were absolutely insisting that Rome's authority was not absolute. There was a higher throne, a greater power, a true Lord.

The same is true today, though the empires have different names. The biblical vision of resurrection insists that the kingdoms of this world are temporary and that their power structures are penultimate at best. Whether those kingdoms come in the form of nation-states, corporations, political parties, or ideological movements, none of them can claim ultimate allegiance. The King has already been appointed, and it is not any earthly ruler.

This does not mean Christians withdraw from public life. Quite the opposite. It means we engage as representatives of a different kingdom, operating by different principles. The power we embody is not the power of coercion, violence, or domination. It is the power of self-giving love, the power that conquered death by submitting to it and rising on the other side.

And here is where it gets uncomfortable for both the political left and the political right. The kingdom of God cannot be co-opted by either tribe. It stands in judgment over both. It refuses to be reduced to anyone's political platform.

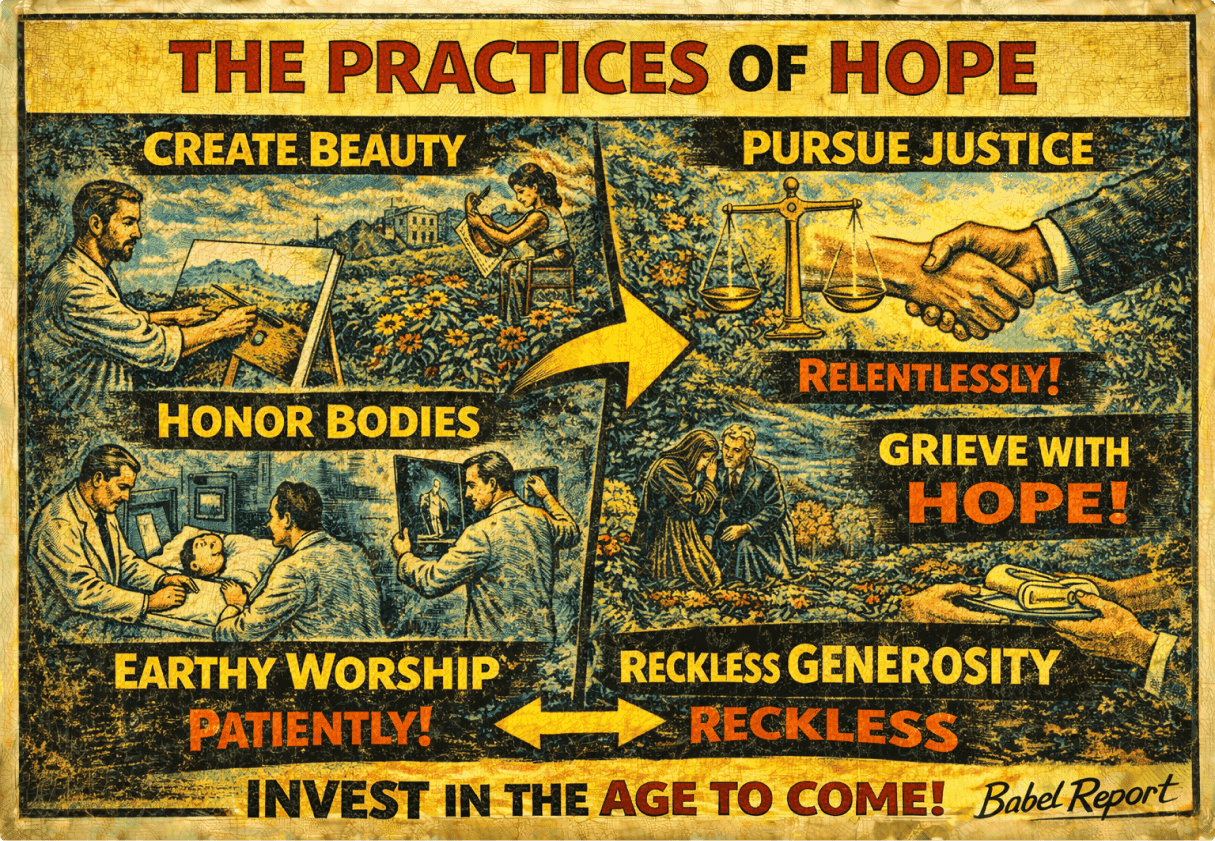

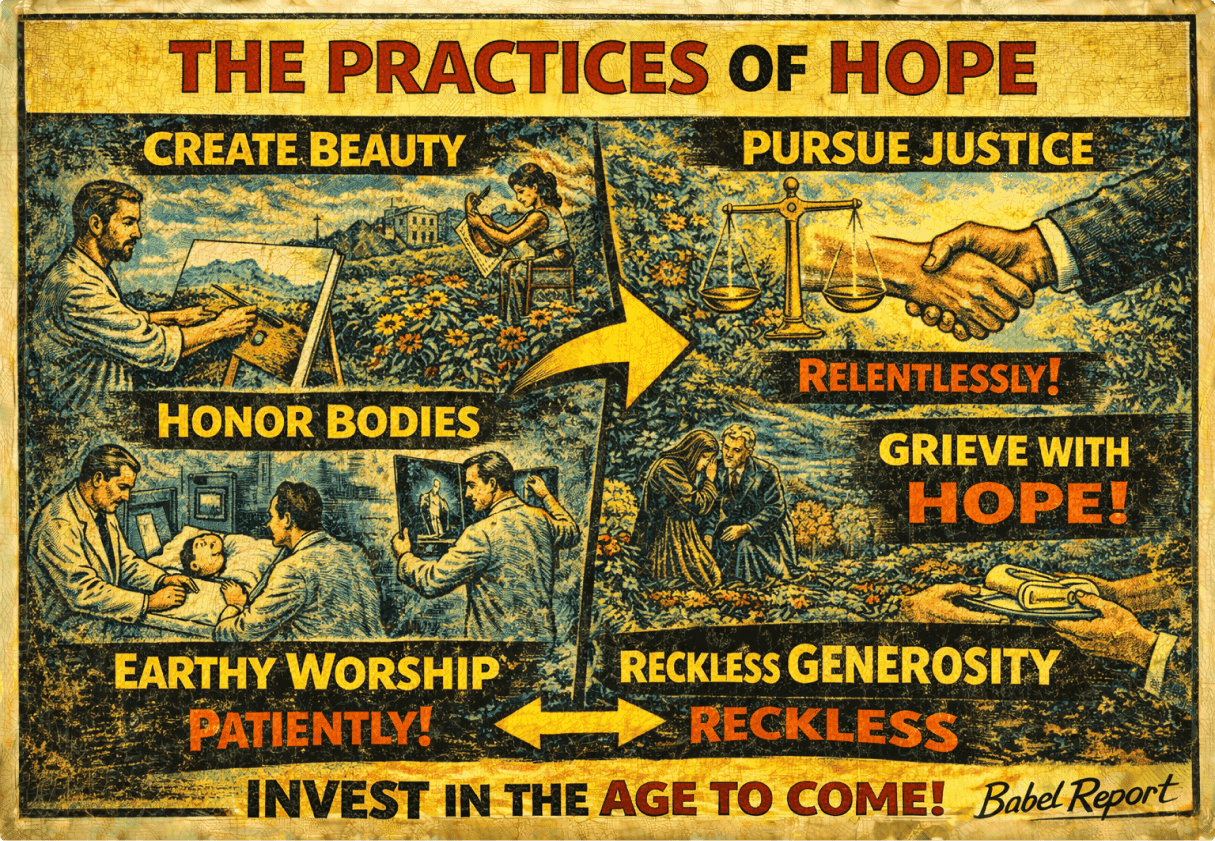

The Practices of Hope

Let me bring this down to ground level. What does it actually look like to live as people of the resurrection in the messy reality of daily life?

It looks like taking beauty seriously. Because if God is renewing the world, then the things we make and cultivate now matter. Art, music, architecture, gardens. These are not distractions from "spiritual" concerns. They are anticipations of the world to come.

It looks like pursuing justice relentlessly but without despair. Because we know the final victory is already secure, we can work for the healing of broken systems without the burden of thinking it all depends on us. We plant trees under whose shade we may never sit, knowing that in the resurrection, all our labor will bear fruit.

It looks like caring for our bodies and the bodies of others. Because the body is not a prison to escape but a temple to honor. Medical care, nutrition, rest, physical pleasure are all ways of affirming the goodness of embodiment.

It looks like grief that is honest but not hopeless. When we stand at gravesides, we weep. Death is still an enemy. But we do not grieve as those who have no hope, because we know this is not the end of the story.

It looks like worship that is earthy and embodied. Bread and wine, water and oil, songs sung with physical voices, prayers offered with physical bodies. We do not flee matter. We consecrate it.

And it looks like generosity that seems reckless by the world's standards. Because if the age to come has already begun, then we can afford to be extravagant in our love. We give without counting the cost, forgive without keeping score, welcome the stranger without demanding credentials. This is not naivete. This is confidence in the resurrection.

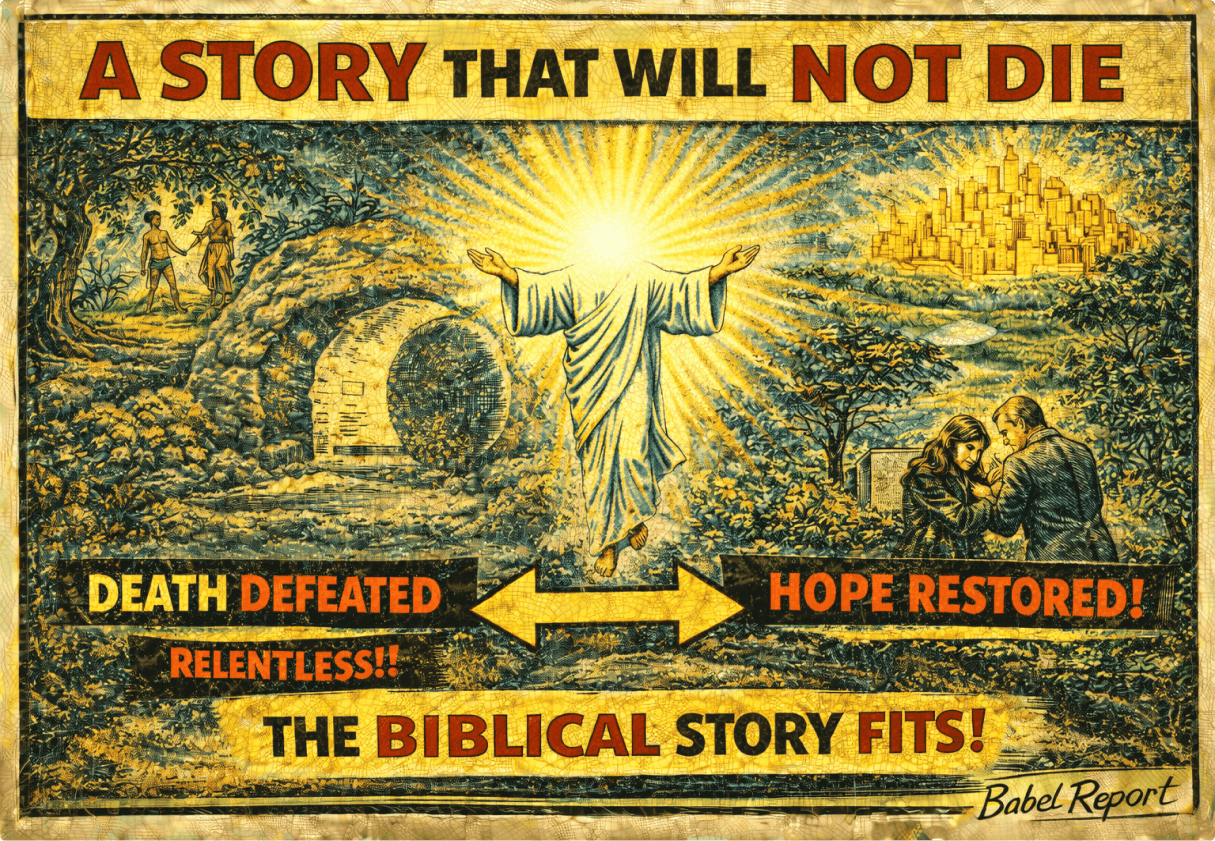

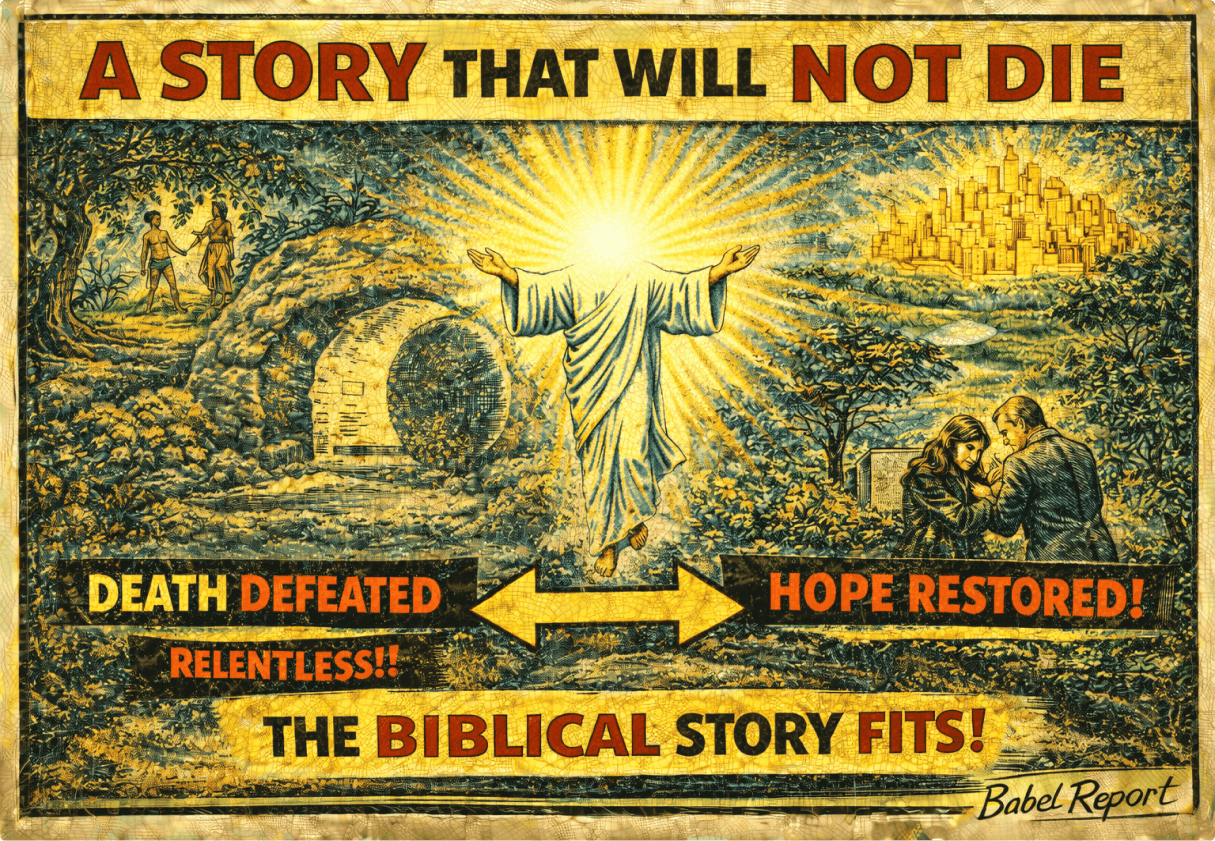

A Story That Will Not Die

I want to return to where we began. The puzzle of death in a culture that claims to have outgrown religious superstition. We cannot seem to stop treating death as an intruder, as something that should not be. And that intuition, I would suggest, is not a vestige of primitive thinking. It is a memory. A faint echo of Eden. A whisper from the future.

The biblical story tells us that we were made for life, not death. That the world was created good and will be restored to goodness. That the exile is not permanent and the King has come to bring us home. You can reject this story. Many do. But what you cannot do (not coherently) is continue to use the moral vocabulary this story provides while denying the story itself.

When you call death "tragic," you are borrowing from the biblical narrative. When you insist that human life has unique dignity, you are standing on the foundation of imago Dei. When you demand justice for the oppressed, you are echoing the prophets of Israel. And when you mourn at funerals, you are testifying (perhaps without realizing it) that this is not how things are supposed to be.

The resurrection of Jesus is the vindication of all these intuitions. It is the proof that death is not natural, that the world is broken but not beyond repair, that the story is not over. And the invitation stands: believe, and live. Even if you were dead.

You may find, as I have over years of wrestling with these questions, that the biblical narrative offers a coherence you cannot find anywhere else. Not because it is comforting (though it is), and not because it is convenient (it rarely is), but because it fits. It accounts for the data of human experience in a way that materialism simply cannot. It explains our moral intuitions, our hunger for justice, our rage against death, our stubborn insistence that beauty and truth and goodness matter.

Perhaps, in a world so fractured and uncertain, this is precisely the story we need. Not an escape from reality, but the deepest reality of all. The reality that death entered through one man's rebellion but life enters through one man's obedience. The reality that the future has invaded the present and the age to come has already begun. The reality that we are not just souls waiting to escape doomed bodies, but image-bearers being prepared to rule wisely over a world finally and fully renewed.

The sentence has been overturned. The appeal has been won. The King has come. And he is making all things new.

The Death We Cannot Accept: Why Resurrection Is the Only Coherent Hope

We live in a curious age. On one hand, our culture treats death as the ultimate taboo. We hide it in hospitals and nursing homes, sanitize it with euphemisms, and invest billions in medical technology to postpone what cannot finally be avoided. On the other hand, we are absolutely saturated with images of death. Our entertainment industry feeds endlessly on mortality. Crime dramas, zombie apocalypses, true crime podcasts. Fascinated and horrified in equal measure.

Here is what strikes me as most remarkable: even the most committed materialist, the person who insists we are nothing more than evolved primates destined for oblivion, still treats death as an intruder. No one eulogizes their pet hamster the way they eulogize grandmother. When a child dies, we do not shrug and say, "Well, natural selection." We rage. We grieve. We erect monuments and light candles and demand justice.

Death means something different when it is human. But if we are all just rearranged stardust, why should it?

This is not a rhetorical trick. It is a genuine puzzle. The vocabulary of our deepest moral intuitions keeps pointing us toward a story we claim not to believe. We speak of death as "untimely," as a "tragedy," as something that "shouldn't have happened." But according to what standard? If the naturalist worldview is correct, death is simply the cessation of biological function. Natural as digestion. Yet we cannot bring ourselves to treat it that way.

And that is the point. We are living off borrowed capital. The moral categories we use to process death, the outrage we feel at its presence, the dignity we insist on in our burial rites? All of this comes from a story. A very old story. One that begins in a garden and ends in a city. One that insists death was never part of the original design.

The Sentence No One Remembers Receiving

The opening chapters of Genesis present us with something far more sophisticated than a children's story about talking snakes. Here is a diagnosis of the human condition that has shaped Western consciousness so thoroughly that we forget where it came from. The narrative tells us that death entered the world through human rebellion, through what the biblical writers call "sin." Not a mistake. Not bad luck. Cosmic treason. The creatures tasked with representing the Creator's wise rule on earth chose instead to grasp at autonomy.

And the result? Exile from the place where heaven and earth overlapped. A sentence of mortality.

Now, one might dismiss this as ancient mythology. Many do, and for reasons they find compelling. But notice what you cannot do (not if you want to remain intellectually honest): continue to use the moral vocabulary this story provides while rejecting the story itself. You cannot call death "unnatural" or "tragic" without implicitly acknowledging that there was supposed to be a different state of affairs. Something was lost. Something broke.

I have spent years in different corners of the Christian world, and the one constant I have discovered is this: the biblical narrative provides a coherence that modern secularism simply cannot match. Not because I need it to be true. Because the alternatives keep collapsing under the weight of their own contradictions. The kingdom of God refuses to be claimed by any political tribe, left or right, and that refusal itself tells us something important about the nature of truth.

The Genesis account is not about an angry deity executing criminals. It is about the fracturing of a relationship that was meant to hold the cosmos together. God (YHWH) created humans in his image. Not as interesting biological specimens, but as his authorized representatives. The ancient term is imago Dei, the "image of God (Alohim)." This was a royal designation. Humans were commissioned to stand between heaven and earth, to reflect the Creator's character to the world and to offer the world's worship back to the Creator.

Kings and priests in one package.

When that relationship shattered, the commission was not simply revoked. It was damaged, distorted. And the symptom of this cosmic dislocation? Death. Not as punishment in the sense of retribution, but as the natural consequence of being severed from the source of life itself. Trees cut off from their roots do not thrive. They wither. This is what the biblical writers mean when they speak of being "in Adam." The entire human family inherited not guilt for Adam's specific act, but the condition his rebellion introduced. Mortality. Decay. Exile from the garden where life was sustained by communion with the Creator.

What the 1st Century Judeans Expected (And Why It Matters)

If you want to understand what the first Christians were claiming, you must first understand what Second Temple Judaism already believed about death and resurrection. This is where most modern readers go astray. We assume "resurrection" is just a poetic way of talking about the soul going to heaven.

The ancient Jews would have found this notion baffling.

By the time of Jesus (YHWShA), the Pharisees believed firmly in resurrection, while the Sadducees rejected it entirely. But notice what the Pharisees meant. They expected a bodily, physical resurrection of the dead at the end of history. Not the survival of an immortal soul, but the reconstitution of the whole person (body and all) when God finally stepped in to put the world right. This was not about individuals "going to heaven when they die." This was about the covenant God of Israel rescuing his people from exile, defeating the powers that held creation hostage, and inaugurating a new age where death itself would be undone.

The key detail is this: they expected it to happen all at once, for everyone, at the end of time. It would coincide with the arrival of God's kingdom in its fullness, when the whole created order would be renewed and the dead would be raised to inhabit the restored world.

So when the early Christians began announcing that Jesus had been raised from the dead, they were not simply reporting that his soul had gone to heaven. They were making a far more audacious claim. They were saying that the end-of-history event had already happened, in the middle of history, to one man. The age to come had broken into the present evil age.

The future had arrived early.

This is why the resurrection accounts in the Gospels are so insistent on the physical details. Jesus ate fish. He bore the scars from the crucifixion. He could be touched. Yet he also appeared in locked rooms and vanished from sight. The disciples were not describing a resuscitated corpse (like Lazarus, who would eventually die again). They were describing something unprecedented: a transformed physical body that belonged to the age to come but was already operative in the present age.

The Apostle Paul would later use the language of "firstfruits" to describe this. In the agricultural economy of the ancient world, the firstfruits were the initial portion of the harvest, offered to God as a sign that the full harvest was coming. Jesus's resurrection was the prototype, the advance demonstration of what God intended to do for all of creation. Not an isolated miracle. The invasion of the future into the present, the beginning of new creation.

The One-Man-In, One-Man-Out Structure

Here is where the story gains its full force. In Romans 5, Paul presents a shocking parallel: just as death entered the world through one man (Adam), so life enters the world through one man (Christ). The logic is cumulative. Adam, as the representative head of the human family, introduced the condition of mortality through his rebellion. Every descendant of Adam participates in that condition. We do not need to commit Adam's specific sin to experience death. We are born into a world where death reigns.

But here is the oddity. If the problem is universal, the solution must be equally universal. And that is precisely what Paul argues. Jesus, as the "last Adam," recapitulates the entire human story and reverses the trajectory. Where Adam chose autonomy and brought exile, Jesus chose obedience and brought restoration. Where Adam grasped at equality with God, Jesus (though he was in the form of God) emptied himself and became obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.

This is not a mere individual act of heroism. This is cosmic.

In the biblical worldview, representatives matter. When the king acts, the nation acts. When the priest offers sacrifice, the whole people are represented. Jesus, as both true Israel and true Adam, succeeded where both Adam and Israel failed. His obedience undid the curse. His resurrection demonstrated that death's power had been broken.

Now, you might say, "But people are still dying." Quite so. And here is where we must understand the biblical claim with more precision. The victory over death is not yet complete in its manifestation, but it is absolutely secure in its foundation. The resurrection of Jesus is the guarantee that what happened to him will happen to all who are united to him. The sentence of death still stands in one sense, but the appeal has been won.

The liberation is in process.

The Two-Stage Drama of New Creation

This brings us to the heart of the matter, and here we must tread carefully because Christian teaching has been muddied by centuries of Platonic influence. When most people think about Christian hope, they imagine something like this: you live a good life, you die, and if you have believed the right things, your soul goes to heaven and lives forever in bliss. The body? Well, that was just a temporary shell.

Good riddance.

This is not the biblical picture. Not even close.

The New Testament presents resurrection as a two-stage process, and understanding this distinction is essential. Let me put it as clearly as I can: the biblical hope is not that we escape the material world to live as disembodied souls in some ethereal heaven. The biblical hope is that heaven comes to earth, and that we (in resurrected, transformed physical bodies) take up our vocational calling as God's image-bearers in a world finally and fully renewed.

The first stage begins with what the early church called the "new birth." But notice how the biblical writers describe this entrance into new life. It is not merely a mental assent or an emotional experience. Peter's sermon on the day of Pentecost gives us the pattern: "Repent and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins, and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit" (Acts 2:38). Here are the three movements of entry into the resurrection life: repentance (a turning from the old age), baptism in the name of Jesus (a public identification with his death and resurrection), and the reception of the Spirit (the down payment of the age to come).

This was not a later theological development. This was how the earliest Christians understood entrance into the new creation from the very beginning. Baptism was not an optional add-on or a mere symbol. It was the threshold moment, the public enactment of dying with Christ and rising with him. When you went down into the water, you were buried with him. When you came up, you were raised to walk in newness of life. And in that same event, you received the Holy Spirit, described by Paul as the "firstfruits" or "down payment" of the age to come. In other words, you were given the life of the future now, in the present.

This is not mere metaphor. The earliest Christians genuinely believed they were participating in the resurrection life of Jesus by the power of the Spirit. They were not simply forgiven sinners waiting to die. They were new creations, already inhabited by the power of the age to come. This is why Paul can say in Romans 8 that those who have the Spirit are already "alive from the dead" in a spiritual sense, even though their mortal bodies are still subject to decay.

But notice the tension. This present life in the Spirit is real and powerful, but it is also incomplete. We groan, Paul says, waiting for the "redemption of our bodies." We are not waiting to be delivered from our bodies, but for our bodies to be delivered. And this is the second stage: the final, physical resurrection at the end of time.

When a Christian dies, they enter what theologians call the "intermediate state." The New Testament uses the language of "sleep" to describe this. Not because the person ceases to exist, but because death has been so fundamentally redefined by Christ's victory that it is no longer the ultimate horror. It is a temporary absence from the body, a state in which the believer is "away from the body and at home with the Lord," as Paul puts it in 2 Corinthians 5. This is a good thing, far better than the suffering and decay of this present age.

But it is not the final goal.

The final goal is the resurrection of the body at the end of history. This is when the scattered people of God are reconstituted as whole persons (body, soul, spirit, all of it) transformed into the likeness of Christ's glorified body. This is what Paul calls the "spiritual body" in 1 Corinthians 15, and the term is crucial. He does not mean a body made of spirit, some ghostly, immaterial thing. He means a physical, material body that is now animated and sustained by the Spirit of God rather than by mere biological processes. It is a body that is incorruptible, imperishable, glorious.

A seed that has been planted and has now burst forth in full bloom.

This is the moment when humans are finally and fully restored to their original vocation. The royal priesthood is re-enthroned. The image-bearers take up their calling to represent God's wise, self-giving rule to the world and to offer the world's worship back to God. And here is the astonishing claim: this re-enthronement of humanity is the specific trigger for the liberation of the rest of creation.

The Groaning of Creation and the Glorification of Humanity

Romans 8 contains one of the most stunning passages in all of Scripture. Paul tells us that the entire non-human creation is in a state of "slavery to decay" and is "groaning" as it waits for something. What is it waiting for? The "revealing of the sons of God." That is, the glorification of redeemed humanity in the final resurrection.

This is not incidental. The biblical worldview insists that the fate of the world is tied to the fate of humanity. When the image-bearers rebelled, the whole creation was subjected to futility. Not willingly, Paul says, but by the will of the one who subjected it (God allowed this as part of the consequences of human rebellion). And now, creation waits. It waits for the moment when the rightful rulers are restored to their thrones. When the kings and priests are finally functioning as they were meant to function, the kingdom (the earth itself) will be set right.

This is why the biblical vision of the future is not about escaping to some non-material heaven. The vision is of "new heavens and a new earth." Not brand-new in the sense of scrapping the old and starting from scratch, but renewed, transformed, purged of corruption. The language in Revelation 21 is remarkably concrete. Nations bringing their glory into the New Jerusalem. A river of life. The tree of life bearing fruit for the healing of the nations.

This is not metaphor for something else. This is the restoration of what was lost in Genesis 3, now glorified and made eternal.

And here is where the story becomes urgently relevant for how we live now. If the Christian hope is just about "going to heaven when we die," then this present world does not matter very much. We become Gnostics, waiting to escape the prison of matter. But if the Christian hope is about the renewal of all things, then what we do in this world matters enormously. The future has already broken into the present through Jesus's resurrection and through the gift of the Spirit. We are not just waiting.

We are participating.

The Already and the Not Yet

This is the strange, productive tension at the heart of Christian existence. The age to come has already begun in Jesus. The powers of the new creation are already at work through the Spirit. But the old age has not yet passed away. We live in the overlap, in what theologians call the "already and not yet."

Already, we have been raised with Christ. Already, we are seated with him in the heavenly places. Already, we are a new creation. But not yet have we received our glorified bodies. Not yet has death been finally and fully abolished. Not yet has the earth been renewed.

This is not a contradiction. This is the way God has chosen to work. The kingdom has been inaugurated, but it has not yet been consummated. And in the meantime, we live as witnesses to the future that is breaking in. We are, to use Paul's language, "Temple-people." Walking points where heaven and earth overlap. Through acts of healing, storytelling, justice, compassion, and beauty-making, we bring the "putting-right" project of God into the present world.

This is not triumphalism. We do not pretend the kingdom has fully arrived. We still live in a world marked by suffering, injustice, and death. But we also do not resign ourselves to cynicism or despair. We work, we pray, we hope, because we know the end of the story.

The resurrection of Jesus is the guarantee that God's project will not fail.

Why the Body Matters (And Why Platonism Fails)

Let me address a common confusion directly. Many Christians, influenced more by Greek philosophy than by Scripture, have come to believe that salvation is primarily about the soul escaping the body. The body is a prison, a temporary shell to be discarded. Heaven is a place where we float as disembodied spirits, perhaps playing harps on clouds.

This is Platonism, not Christianity. And it fails on multiple levels.

First, it dishonors the creation. The biblical story begins with God declaring the material world "very good." Matter is not evil. Embodiment is not a problem to be solved. The problem is sin, corruption, decay. Things that have infected the good creation but are not intrinsic to it.

Second, it makes nonsense of the incarnation. If the goal were to escape physicality, why would God become flesh? Why would the Word take on a body, live in it, die in it, and then rise in it? The incarnation is not a detour. It is central to the whole story. God affirms the goodness of materiality by entering into it fully.

Third, it undermines mission. If this world is just a sinking ship and heaven is the lifeboat, then why bother with culture, art, justice, or ecology? Just save souls and wait for the end. But if God intends to renew the earth, if our resurrection bodies will inhabit a transformed physical world, then what we do now has eternal significance. We are not killing time. We are planting seeds.

This is why Paul insists so strenuously in 1 Corinthians 15 that the resurrection is physical. He uses the metaphor of a seed. You plant a bare kernel, and what comes up is something far more glorious, but it is still a plant. There is continuity and transformation. The resurrection body is not a completely different thing. It is this body, purged of corruption, made imperishable, and animated by the Spirit.

Paul gives us more detail. He describes the current body as a "natural body" (or more literally, a "soul body"), meaning it is animated by the life force that all creatures share. But the resurrection body is a "spiritual body," meaning it is a physical body now powered and sustained by God's own Spirit. Think of it as an upgrade in operating system. The hardware remains recognizably the same (Jesus still bore his scars), but the software that runs it is fundamentally different.

Incorruptible. Glorious. Imperishable.

This distinction matters because it shows us that the biblical hope is not about moving from physical to spiritual, from material to immaterial. It is about moving from corruptible to incorruptible, from mortal to immortal, from enslaved to liberated. The resurrection body is more physical than our current bodies, not less. It is what the human body was always meant to be.

What We Get Wrong About Heaven

While we are on the subject, we need to address another persistent confusion. Ask the average person on the street what Christians believe about the afterlife, and they will probably say something about "going to heaven when you die." And to be fair, many Christians would say the same thing. But this is at best a half-truth, and at worst a profound distortion of the biblical vision.

The intermediate state (being "with the Lord" after death but before the resurrection) is real, and it is genuinely better than our current existence. Paul says as much. But it is not the ultimate destination. It is a waiting room, not the final home.

The ultimate destination is not "heaven" in the sense of some distant, ethereal realm far removed from earth. The ultimate destination is the renewed earth, the place where heaven and earth have finally and fully merged. This is what Revelation 21 describes: the New Jerusalem coming down from heaven to earth. God's dwelling place and humanity's dwelling place becoming one. The exile finally over. The garden restored and glorified into a city.

Why does this matter? Because if we think the goal is to "go to heaven," we will inevitably devalue the material world. Why care about justice on earth if the righteous are just waiting to escape? Why pursue beauty or truth or goodness in this world if the real action is somewhere else? But if the goal is the renewal of earth, then suddenly everything we do here carries weight. Our work, our relationships, our creativity, our justice-seeking are all part of the project.

This is not "social gospel" liberalism that abandons personal salvation for political activism. Nor is it fundamentalist escapism that abandons the world for pie-in-the-sky otherworldliness. It is the biblical vision that holds both together: God saves persons and God renews the world. The two cannot be separated.

Rehearsing for Resurrection

So what does it look like to live in light of this hope? It means treating the present as training for the future. Paul tells the Corinthians that because we know the resurrection is real, our labor is not in vain. What we do in the body matters. The habits we form, the character we develop, the work we produce are all part of the material God will use in the new creation.

This is not works-righteousness. We are not earning our place in the kingdom through moral effort. We are justified by grace through faith, full stop. But justification is not the end of the story. It is the beginning. Having been declared members of God's family, we are now being formed into the kind of people who can wisely exercise the royal priesthood we are being restored to.

Think of it this way. If you knew you were going to be a surgeon, you would spend years in training. Not because the training earns you the position, but because the position requires certain skills and habits. In the same way, if we are going to be rulers and priests in the new creation, it makes sense that we would spend this life developing the virtues required for that vocation.

Compassion. Justice. Wisdom. Self-giving love. These are not arbitrary rules. They are the character traits of the age to come, and we practice them now as a form of anticipation. We are rehearsing for the performance that will never end.

This is why Christian ethics matter. Not because God is a cosmic policeman waiting to punish infractions, but because the way we live now is shaping us into the people we will be forever. The habits we form are not left behind at death. They are transformed and purified, yes, but they are also carried forward. The person you are becoming now is the person you will be in the resurrection.

The Political Implications of Bodily Hope

I need to address something that will make some readers uncomfortable. The biblical vision of bodily resurrection has unavoidable political implications. Not in the sense of partisan politics (I have no allegiance to left or right, Democrat or Republican), but in the sense that it makes claims about how power works and who the true King is.

In the Roman world, the language early Christians used was directly subversive. Calling Jesus "Lord" (Kyrios) and "Savior" were the exact titles Caesar claimed. Announcing the "good news" (euangelion) of Jesus's kingdom was a rival proclamation to the Roman imperial gospel. When Paul wrote that every knee would bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, his readers would have immediately understood: not Caesar. Jesus.

This was not merely spiritual language. It was a public announcement that the world had changed, that a new King had been installed, and that ultimate allegiance now belonged elsewhere. The early Christians were not trying to overthrow Rome through violent revolution, but they were absolutely insisting that Rome's authority was not absolute. There was a higher throne, a greater power, a true Lord.

The same is true today, though the empires have different names. The biblical vision of resurrection insists that the kingdoms of this world are temporary and that their power structures are penultimate at best. Whether those kingdoms come in the form of nation-states, corporations, political parties, or ideological movements, none of them can claim ultimate allegiance. The King has already been appointed, and it is not any earthly ruler.

This does not mean Christians withdraw from public life. Quite the opposite. It means we engage as representatives of a different kingdom, operating by different principles. The power we embody is not the power of coercion, violence, or domination. It is the power of self-giving love, the power that conquered death by submitting to it and rising on the other side.

And here is where it gets uncomfortable for both the political left and the political right. The kingdom of God cannot be co-opted by either tribe. It stands in judgment over both. It refuses to be reduced to anyone's political platform.

The Practices of Hope

Let me bring this down to ground level. What does it actually look like to live as people of the resurrection in the messy reality of daily life?

It looks like taking beauty seriously. Because if God is renewing the world, then the things we make and cultivate now matter. Art, music, architecture, gardens. These are not distractions from "spiritual" concerns. They are anticipations of the world to come.

It looks like pursuing justice relentlessly but without despair. Because we know the final victory is already secure, we can work for the healing of broken systems without the burden of thinking it all depends on us. We plant trees under whose shade we may never sit, knowing that in the resurrection, all our labor will bear fruit.

It looks like caring for our bodies and the bodies of others. Because the body is not a prison to escape but a temple to honor. Medical care, nutrition, rest, physical pleasure are all ways of affirming the goodness of embodiment.

It looks like grief that is honest but not hopeless. When we stand at gravesides, we weep. Death is still an enemy. But we do not grieve as those who have no hope, because we know this is not the end of the story.

It looks like worship that is earthy and embodied. Bread and wine, water and oil, songs sung with physical voices, prayers offered with physical bodies. We do not flee matter. We consecrate it.

And it looks like generosity that seems reckless by the world's standards. Because if the age to come has already begun, then we can afford to be extravagant in our love. We give without counting the cost, forgive without keeping score, welcome the stranger without demanding credentials. This is not naivete. This is confidence in the resurrection.

A Story That Will Not Die

I want to return to where we began. The puzzle of death in a culture that claims to have outgrown religious superstition. We cannot seem to stop treating death as an intruder, as something that should not be. And that intuition, I would suggest, is not a vestige of primitive thinking. It is a memory. A faint echo of Eden. A whisper from the future.

The biblical story tells us that we were made for life, not death. That the world was created good and will be restored to goodness. That the exile is not permanent and the King has come to bring us home. You can reject this story. Many do. But what you cannot do (not coherently) is continue to use the moral vocabulary this story provides while denying the story itself.

When you call death "tragic," you are borrowing from the biblical narrative. When you insist that human life has unique dignity, you are standing on the foundation of imago Dei. When you demand justice for the oppressed, you are echoing the prophets of Israel. And when you mourn at funerals, you are testifying (perhaps without realizing it) that this is not how things are supposed to be.

The resurrection of Jesus is the vindication of all these intuitions. It is the proof that death is not natural, that the world is broken but not beyond repair, that the story is not over. And the invitation stands: believe, and live. Even if you were dead.

You may find, as I have over years of wrestling with these questions, that the biblical narrative offers a coherence you cannot find anywhere else. Not because it is comforting (though it is), and not because it is convenient (it rarely is), but because it fits. It accounts for the data of human experience in a way that materialism simply cannot. It explains our moral intuitions, our hunger for justice, our rage against death, our stubborn insistence that beauty and truth and goodness matter.

Perhaps, in a world so fractured and uncertain, this is precisely the story we need. Not an escape from reality, but the deepest reality of all. The reality that death entered through one man's rebellion but life enters through one man's obedience. The reality that the future has invaded the present and the age to come has already begun. The reality that we are not just souls waiting to escape doomed bodies, but image-bearers being prepared to rule wisely over a world finally and fully renewed.

The sentence has been overturned. The appeal has been won. The King has come. And he is making all things new.

EXPLORE MORE

Worldviews at War

Why our debates feel like holy war: the hidden worldview clash behind political rage and what the Christian story offers both sides.

LEARN MORE

The Money God

Wealth promises security but demands worship. Mammon, the ancient money-god, still enslaves. Jesus offers freedom through resurrection faith.

LEARN MORE

The Pastor's Palace

From Eden, the temple, and the Kingdom of God. We are the new temple God wants to dwell in, not buildings made by hands.

LEARN MORE

EXPLORE MORE

Worldviews at War

Why our debates feel like holy war: the hidden worldview clash behind political rage and what the Christian story offers both sides.

LEARN MORE

The Money God

Wealth promises security but demands worship. Mammon, the ancient money-god, still enslaves. Jesus offers freedom through resurrection faith.

LEARN MORE

The Pastor's Palace

From Eden, the temple, and the Kingdom of God. We are the new temple God wants to dwell in, not buildings made by hands.

LEARN MORE

EXPLORE MORE

Worldviews at War

Why our debates feel like holy war: the hidden worldview clash behind political rage and what the Christian story offers both sides.

LEARN MORE

The Money God

Wealth promises security but demands worship. Mammon, the ancient money-god, still enslaves. Jesus offers freedom through resurrection faith.

LEARN MORE

The Pastor's Palace

From Eden, the temple, and the Kingdom of God. We are the new temple God wants to dwell in, not buildings made by hands.

LEARN MORE